Next-Level Thinking: Level 42 interview

By Classic Pop | November 5, 2018

Inspired as a youngster by the jazz greats, Mark King soon reinvented bass playing and took Level 42 into the upper echelons of the pop charts with an irresistibly funky sound. Written by David Burke.

When Classic Pop catches up with Mark King, the Level 42 bass supremo is in winningly feisty form. “I’m the guy who has been pushing this ahead and making sure it kept going through thick and thin,” he says. “Everybody needs to have a dose of reality and realise that these things don’t just run on their own. Somebody has to push this through all the time. The reality of why the band is still here is because yours truly kept it going.”

With the latest incarnation of the band about to embark on an extensive UK tour in October, supported by The Blow Monkeys, the legacy, it seems, is in rude health. So much so that King feels no urgency to work on new material any time soon. “I get an idea and I think it sounds great at 11 o’clock at night. Then I go in the next day with a cup of coffee and I think, ‘this sucks arse’. Which always begs the question, ‘is that really what people want to hear from us?’ After this amount of time, you’ve got these fans who come out and love us for the music that we’ve made. And it’s a hell of a catalogue, over 300 songs that we’ve got to choose from. Social media affords you this sort of window on what the hardcore fans, the real fans, really want. They’re not saying, ‘Let’s have some new music’. They’re saying, ‘Are you going to play Good Man In A Storm on this tour? You’ve never played it live.’

“Bear in mind that a lot of the audience will want to hear the bankers, I suppose – Something About You, Lessons In Love, Running In The Family. I love playing those songs, too, so it’s really incumbent on me as the band leader to deliver them. If you want to see an audience en masse glaze over, stand on stage and say: ‘We’re going to play the brand new album from start to finish.’ That’s terrifying for them. They’re really not into it.”

Level 42 currently features King’s brother, Nathan, on guitar, as well as original keyboardist Mike Lindup, now in his second stint. King finds that the consummate musicianship of such old hands mitigates the monotony of rolling out the staples night after night.

“The nearest I would get to becoming fed up playing the old songs is if we’ve been on the road for two months, say. But then what happens with a band like Level 42 – and I’m very proud of this – is that everybody just starts jamming. There are sequencers running the show, because there has to be some sort of choreography. But within that, if the players are up to it – and they most certainly are in the band – you can really take an idea and run with it. That becomes the fun, because we start messing around and everything gets incredibly relaxed, come the encore. Plus, the band these days is a seven-piece with a brass section. When you put a brass section in songs that never had any brass there in the first place, they take on another life.

“That keeps it exciting and fresh. I love the fact that everyone is in the band because they’re fantastic players. It would be ridiculous not to say, ‘Look, you know this tune – run with it, see what you can come up with’.”

Needles in the Groove

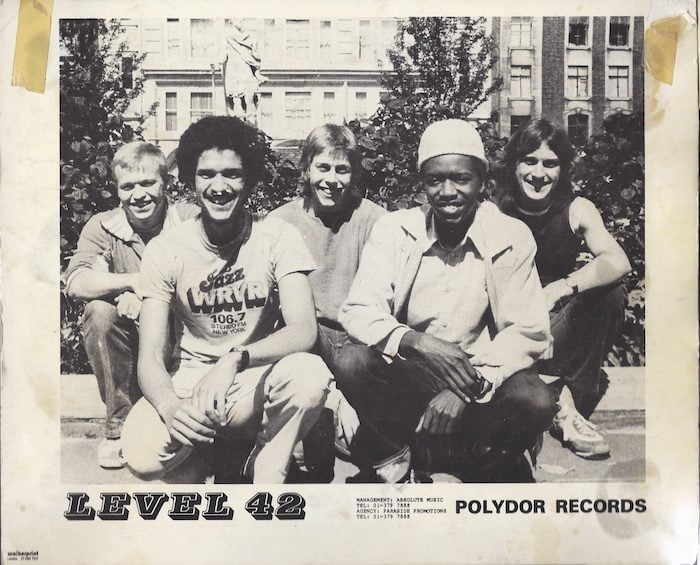

The 59-year-old founder member of the Isle Of Wight outfit first swapped the drum kit for the bass guitar, then augmented the latter with occasional vocal duties before assuming the frontman role proper on 1982’s breakthrough album, The Pursuit Of Accidents. When King formed Level 42 with the Gould brothers, fellow Isle of Wighters Phil and Rowland (alias Boon), they were jazz-funk aficionados, deep into Miles Davis, John McLaughlin and Keith Jarrett. While this was sonic worlds away from the pop terrain that became their regular stomping ground in the 80s, King had been a fan of music of all kinds at eight years old – and his first vinyl purchase was a Cream album.

“I wanted to be a drummer like Ginger Baker, who just sat there with this mad red hair and this sort of insane grin on his face. Then you had Jack Bruce, the singing bass player who was playing these phenomenal basslines. And then, of course, Eric Clapton – old Slowhand giving it the big licks. That first power trio just really got me. But it was the musicianship that hooked me in.

“That led me onto this trip of getting into Buddy Rich. Then you listen to Jimi Hendrix and there was a drummer who played with him during the Band Of Gypsys period called Buddy Miles. When I followed that through, I found out that he had played on a John McLaughlin album, so suddenly, I was into John McLaughlin. There was this incredible lineage, this musicality. Having been introduced to John McLaughlin, you find out he’d played with this guy called Miles Davis!

“Bear in mind, I’m still only 14 years old and that living on the Isle Of Wight was very hard. Nowadays, the kids have got it so easy – they just Google this shit and everything that we’ve ever done is now all up there. If you want to see me at my best, just look at the Rockpalast [a German TV show] stuff back in ’83 or ’84, because that’s when I was doing it new and out of the box. It was fresh. You have this period in your life when ideas are sparking and it’s going nuts. You are really charting new territory and new ground with your technique. If I think back to that period, it was seminal for the band. Not only was the first break-up about to happen, but when I think of the songs to come – there was such a lot that we hadn’t even thought of yet.”

Leaving Me Now

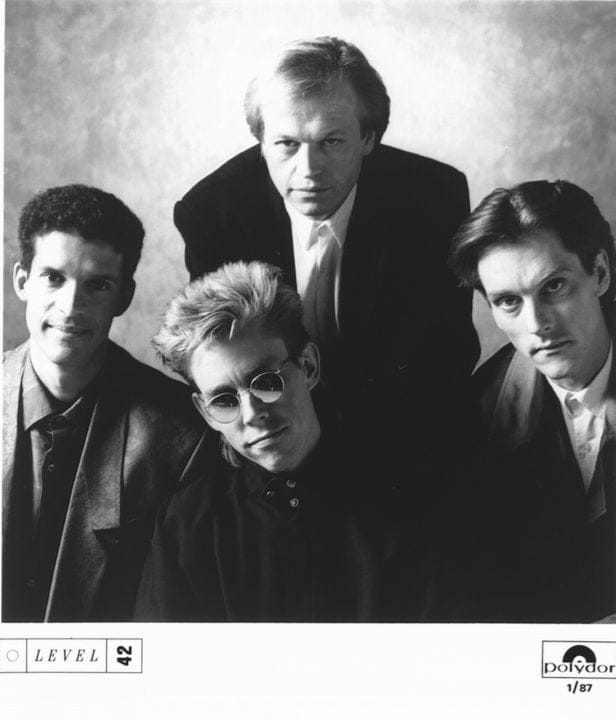

Ah, yes – the first break-up. Both Gould brothers quit around 1987, Boon because of exhaustion, Phil over his thorny relationship with King. Before long, replacements were recruited in the shape of Gary Husband and Alan Murphy, ex-Go Wester and sessioner on albums by Kate Bush, David Bowie and Scritti Politti. “That was the most fun I had in the 80s, because we just laughed like drains,” says King. “It was sadly cut short because Alan Murphy passed away around 18 months later.

“Musically, we took a step in another direction when Gary Husband and Alan Murphy joined. It was one that I was really excited about. We’d already done that difficult thing of having No.1 singles around the world and shipping vast quantities of albums. But it had taken us six, seven years to get to that point and I really missed the edge we had when started out, when we used to jam more.

“When Phil left shortly after Boon had left, that left a hole. I said to Mike Lindup: ‘I’m going to carry on, are you coming with me?’ He said: ‘Absolutely’. Both of us liked the idea of making it a bit edgier.”

For many fans of Level 42, though, that first line-up retains a special place in their affections. Alongside King, the Goulds and Lindup was Wally Badarou, the Frenchborn synth specialist from Benin, West Africa, who remained a de facto member rather than officially part of the group.

“He was more mature than us and he had a unique way of working with synths and sounds, which was new to us. John Gould, our first manager and Phil’s brother, was a product manager at MCA Records. Robin Scott had this band called M and they had this song Pop Muzik, which became No.1 everywhere. They actually didn’t have a band, as such. The keyboard player they used was Wally.

“So, when they were laying all this stuff down in 1980, it just so happened that we were in the studio laying down stuff for Elite Records. This is how Wally came on board.

“We got on like a house on fire straight away and it was obvious that musically, it was a perfect fit for us. I would have loved it if Wally had said: ‘Yeah, I’m coming in with the band’, but he had his upcoming solo career and he was very good mates with [Island Records boss] Chris Blackwell, who was financing him… He had too much going on to chuck it in and take a roll of the dice with these English kids.

“We made the first record and Wally featured on it. Then the second record came along really fast. That was another seminal moment for us, because that launched me upfront as this thumping bass player, which seemed to take people by surprise. I was only really trying to do what I’d been hearing coming across from America… I’d been listening to Stanley Clarke and Larry Graham.

“The idiom they were thumping the music in wasn’t as broad a spectrum as pop, so I’d somehow managed to leap the fence with that, and we were straight out into the pop mainstream. It happened to coincide with our first European tour, when we opened for The Police. We had a hit in Holland with Love Games, so when we finished that tour, we played 13 gigs in Holland on our own. I split my thumb and lost my voice, plus there were so many drugs going on, it was just incredible. It was pretty meteoric… I only had to cast my mind back to when I was working a milk round on the Isle Of Wight!”

Low-End Theory

Nobody who watched Top Of The Pops regularly in the 80s will ever forget King’s unique bass technique. The instrument strapped high to his chest, he thumb-slapped the strings with an intensity that made you concerned for his welfare.

“My style is different. I really took the ball and ran with it from ’80 to ’84. I changed things, so it wasn’t the same way the American guys were doing it. One of the joys for me in this business is that a few years back, Larry Graham was touring with Graham Central Station and he gave me a call, wondering would I come and join him at the Jazz Café to do this bass-off? So, standing side-by-side with him, you got to see at first-hand the styles were so different…

“My style came very much from the drumming side of things. It’s like playing a percussion instrument – both hands are involved all the time. It’s like a conga player or a bongo player would be playing, as opposed to just using a pick and the right hand picking out notes.”

King still acknowledges that Level 42 Mark I (no pun intended) were the band at their most creative. “We were four lads who got together, and came up with all these ideas. This was the first band for all of us, so there were no rules. Of course, being brothers, the sibling thing was definitely an issue – plus their older brother was managing. You had this triad of lads that were family, and it’s very hard to have a rational discussion when it boils back down to: ‘Well, you were always like that. You held my head under the bath water!’.”

King remains good friends with Boon Gould, even after the latter’s exit. In fact, Boon wrote the lyrics on 1988’s Staring At The Sun. “He found the pressures of touring too much. Some of us can put on a fake mask on stage, but he’s a very shy guy. You hide behind some kind of persona, but some people can’t do that and find it excruciating being on stage in front of people. Boon suffered from that.”

While an olive branch was extended to (and accepted by) Phil Gould in 1993, the reunion was short-lived. “He made it clear that although he wanted to do the studio thing, he didn’t want to go back on the road again, which isn’t ideal. We did write and record the album together. But it didn’t end well. Then, if you wind forward, after I acquired the name back in 2002, I tried getting the original line-up back together again in 2003 to record.”

Mark recalls the ill-fated reunion. “I had Phil and Boon, Wally and Mike, all sat in my house on the Isle Of Wight, writing some songs. It lasted about four days and then just fell apart. I could see that the old problems and tensions really hadn’t gone away.

“It didn’t matter about looking back with rose-tinted spectacles and thinking how wonderful it was. Once you go down a road and you cross some paths, you can’t just go back. It’s not just a case of not rebuilding burned bridges. It’s a case of that was then and this is now – things have moved on and changed. I was married and then I wasn’t married – that’s how it is.”

But for now, at least in the context of the present Level 42, King is enjoying a renewed period of marital bliss.

Read more: Stepping Out of the Shadow: Dannii Minogue interview