Stephen Duffy Interview: ‘I appreciate the past but I’ve never been nostalgic’

By Classic Pop | July 29, 2019

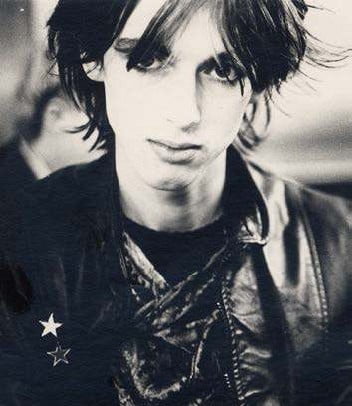

He left Duran Duran before they hit big and only ever achieved two Top 20 hits in his career. But why is the man formerly known as Stephen ‘Tin Tin’ Duffy so loved and admired now? Classic Pop meets the intriguing pop chameleon to find out more about the real man behind the many guises…

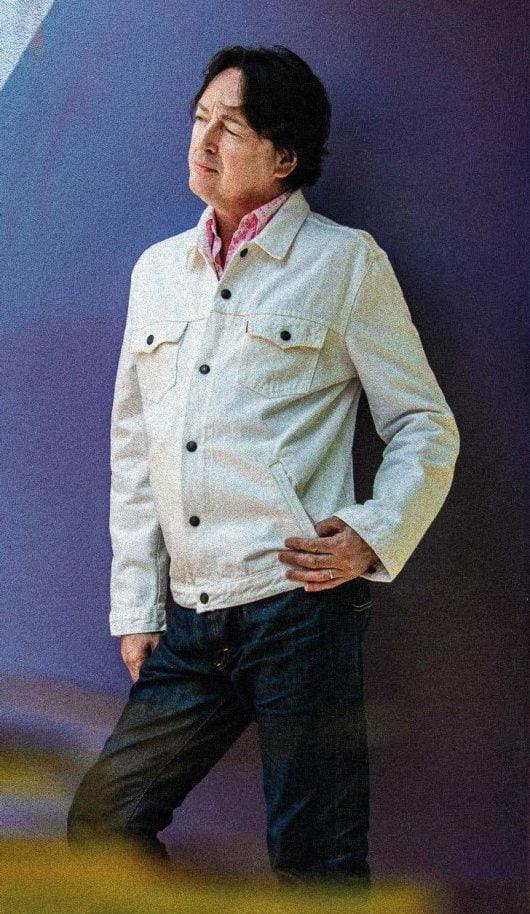

Nursing a pint of Cornish stout in a dark harbourside tavern, a softly-spoken, unassuming man shares anecdotes on daily life. You know, those things we can all relate to – surviving the school run, the latest round of Brexit uncertainty, forming a band with a bunch of college mates.

“I got in with a bad crowd,”explains a deadpan Stephen Duffy, “…started Duran Duran.”And then that signature mischievous grin, one that appears whenever he casually drops a bombshell – one of many scattered over a sprawling two-hour conversation, covering everything from Margaret Thatcher to the joys/evils of streaming. Other choice nuggets include turning down Madonna, forming a Britpop supergroup – oh, and shifting millions of records with some bloke called Rob.

They Call Him Tin Tin

They Call Him Tin Tin

The man who once called himself Stephen ‘Tin Tin’Duffy is a fascinating character, one who has typically operated from the periphery, remaining wilfully out of step with what’s going on. As a result, record labels over the years have struggled with where to place him. But perhaps that’s been his biggest strength and it hasn’t stopped him contributing to album sales approaching 30 million (a conservative estimate).

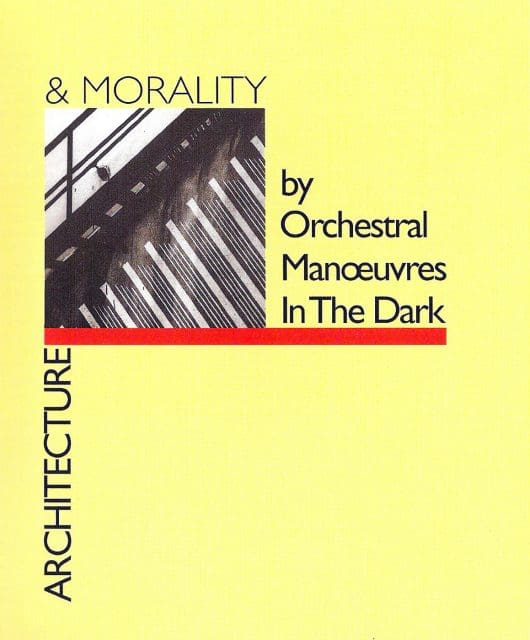

The danger of emerging from a certain scene is remaining forever shackled to it. Yet Stephen Duffy has transcended his original synth-pop guise to cover a huge landscape across a career spanning four decades. He’s had as many incarnations as Bowie: That guy who founded (then promptly left) Duran Duran. 80s pop ‘one-hit wonder’. Early dance pioneer with Dr Calculus mdma.

English folk raconteur. Britpop poet. Honorary Barenaked Lady. That guy who co-wrote one of Robbie Williams’most successful records. One-half of The Devils with former bandmate Nick Rhodes… In other words, the most prolific one-hit wonder you’re likely to meet.

So, who is the real Stephen Duffy? Charming, affable and habitually self-deprecating, he’ll set himself up only to tear himself down again after a dramatic pause. He claims, tongue-in-cheek, to have been dropped by every major record label in the world – in itself a considerable accomplishment. But, by the same token he must have been signed by them all, too.

‘People take me places but I’m very happy not going anywhere. By the time I was 26, I never wanted to visit a nightclub again. I’d done so much promotion!’

He’s even had a label named in his honour, Needle Mythology, after his song of the same name – “a different kind of needle, of course.”

He’s had his share of demons. Now approaching 60, married with a daughter and living at an imposing address in a picturesque Cornish seaside town, it seems to have turned out alright in the end.

“We’ve got the studio in the basement and a couple of olive trees in the back garden,”he says wistfully. “People take me places, but I’m very happy not going anywhere. I mean, I’ve been out! When I was 25 they kept on taking me out to nightclubs. By the time I was 26 I never wanted to visit a nightclub ever again, I’d done so much club promotion!”

Fee-Fi-Fo-Brum

So, let’s talk about going out… Born in 1960, Stephen Duffy grew up in Birmingham in a typical 1930s house. Music was always there, Stephen often performing with older brother Nick. He recalls first hearing The Beatles aged three or four. “You saw the incredible effect that had on people, even before you understood what it was. The first band I ever went to see were The Incredible String Band at Birmingham Town Hall, I was nine or 10. And then Fairport Convention and all of that Witchseason/Joe Boyd stuff was incredibly important to me, and obviously Dylan. Then, there was punk…”

It was around this time that he enrolled at art college, and got in with that ‘bad crowd’.

“The amazing thing is it’s actually 40 years next month since the first [Duran Duran] gig. We’d arrived at art college… I’d seen the bands John [Taylor] had been in, but we didn’t know each other. I walked over to him and the first thing I said to John was, ‘Do you want to start a band?’So, we wrote some songs when we should’ve been working – that was September. By April, the next year, we’d got Nick [Rhodes] on synth and we’d written these songs… I’d written these songs. We rehearsed and then performed them at the lecture theatre – and that’s kind of what I’ve done with my life since. You write 10 songs, you perform them live or you make a record. This next Lilac Time record will be the 20th time of doing that!”

His eyes suddenly light up. “Actually, I think I named them! John said, ‘Did you see Barbarella on the television last night? There’s this character called Durand Durand’– with a ‘D’on the end… We were in the art college at the time, so I went and got the type and typeset ‘Duran Duran’. I don’t think they had more than two ‘D’s… maybe they did! So by doing that, I think maybe I should…”

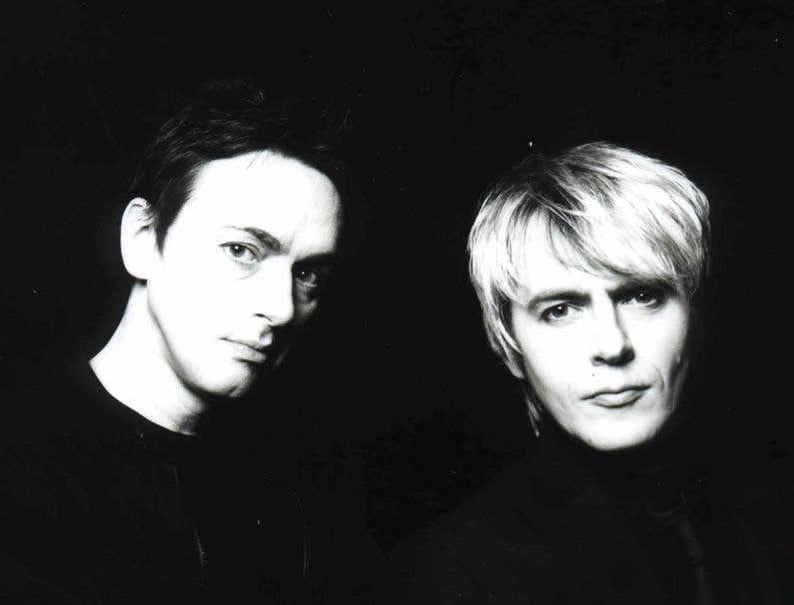

Speak to your lawyers? “Definitely,”he laughs, “it’s my name, isn’t it! No… but, obviously, I still talk to Nick. We made The Devils album.”

2002’s supremely overlooked Dark Circles was the result of discovering original tapes from those early days followed by a chance encounter with Nick. In other words, the album Duran Duran might have made with Stephen at the helm. An artier, darker proposition.

“Yes, but we would’ve been supporting Echo & The Bunnymen! I don’t think it’s what they’d have wanted.”

“Yes, but we would’ve been supporting Echo & The Bunnymen! I don’t think it’s what they’d have wanted.”

At this point, Bowie was setting the bar of artistic expression. “In that Duran age when I was there, ‘78 and ‘79, it was Low and Heroes. You’d listen to these snatches of songs like Always Crashing In The Same Car – this incredibly oblique, fractured thing – and think, ‘This is exactly what we have to do!’”

Perhaps it was already clear by now that they were destined to take different paths – one ‘oblique and fractured’, the other firmly rooted in the pop limelight.

“I did a live radio interview last Friday, and every time we came back, it was like, ‘Now we’re with the founding member of Duran Duran’. Like, Jesus, do we really have to keep banging on about this?!”

But, it’s a part of his identity, though by no means the only thing to define him. “I’m completely happy with it.

I think it’s probably more annoying for them,”he says with a grin, “because it sort of undermines their unity having this weirdo who is known as being the ‘founder member’. I’m more of a thorn in their side, than they are in mine!”

Duffy’s exit marked the start of a colourful career, sealed with the hit Kiss Me. But also a career characterised by leftfi eld choices, much to the frustration of his latest label. Second solo album, Because We Love You, produced by Smiths collaborator Stephen Street, saw him increasingly ditch the synths in favour of more organic, acoustic instrumentation.

‘It was an amazing opportunity to work with an artist who just didn’t care. He didn’t even call himself Robbie Williams at that point’

“But the record company kept on saying, ‘No, we really just want you to be a dance artist. Maybe if you don’t sing and get a girl in to sing!’”Listening to Nick Drake changed everything. “It hit me that this was my thing. So I went and recorded the first Lilac Time record, knowing we’d part company.”

Of all the guises he’s adopted, this is clearly the one he’s most comfortable with, his natural fit.

“I was 26 and at some point you have to do what you want to do, don’t you?”He breaks into character. “I wanted to get loaded and have a good time… and that’s what I went and did. When you’re young, you think, ‘I’m 30 in four years, I’ve just got to get on with it now.’I thought when you’re 30 you’re going to be a bald, old man and nobody was going to take you seriously. I really did, I was very depressed. On my 29th birthday I was virtually suicidal. So that’s why I did it then, and ever since I’ve done it because it’s what I naturally do. I enjoy country music more than any other, like George Jones and Lefty Frizzell. It doesn’t stop me doing other music, but that’s my thing.”

Despite a steady underground following, both solo and with The Lilac Time, another big breakout hit remained elusive. However, Duffy’s increasingly assured catalogue was gaining him some influential fans. His friendship and collaborations with a young devotee, Steven Page, led to repeated multi-platinum success with the latter’s band, Barenaked Ladies.

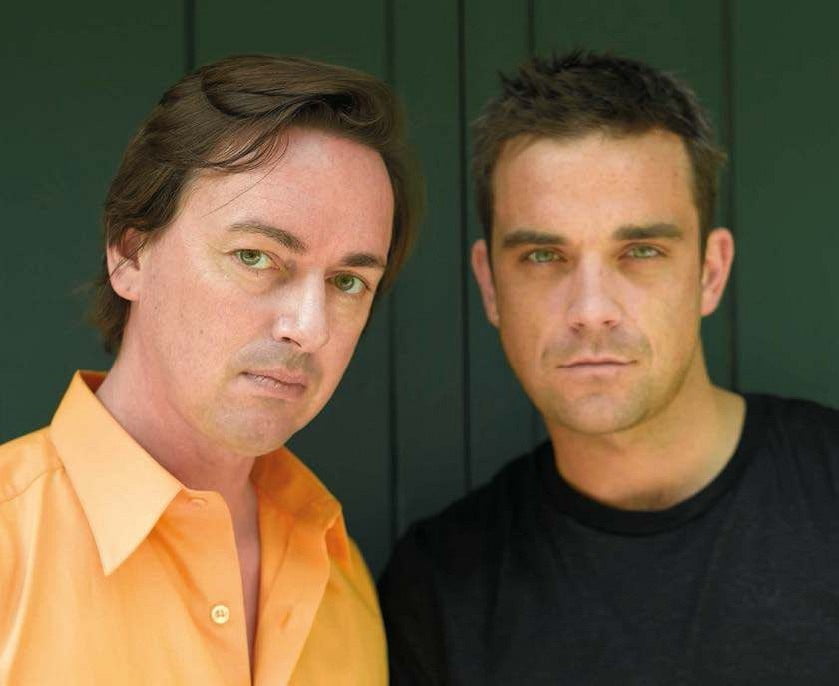

Then another fan, ‘that guy who left Take That’, came calling. A No.1 single, Radio, on Robbie’s globe-conquering Greatest Hits cemented a three-year writing partnership. The resulting album, Intensive Care, sold a million in its first week alone, with sales at the last count approaching 10 million worldwide.

It’s another association that’s proved both a blessing and a curse. A commercial high-water mark, but also an anomaly that doesn’t necessarily sit right with his story.

“It’s certainly not something I would erase. It was such a fantastic opportunity to use all of my skills, and to work in those great Los Angeles studios, like A&M, where The Carpenters and Joni Mitchell recorded. Apparently, the ghost of Karen Carpenter walks the corridors at night. And I got to work with Beck’s dad [David Campbell], who has arranged the strings on so many amazing records.”So what was the writing process with Rob like?

“We jammed. We spent hours just kind of… he played bass, I played guitar, he played the synth, I played the maracas.

So everything came from a completely different place. But it was an amazing opportunity to work with an artist who just didn’t care. He didn’t even want to call himself Robbie Williams at that point. It was just amazing fun… and I got to live in an LA penthouse for three years!”

‘I appreciate the past but I’ve never been nostalgic’

They then took the record on the road, with Stephen as musical director. “We did this huge world tour, but he wasn’t into it really… I think he wanted to get into the Rudebox thing and do even more electronic music.”

Suddenly now finding himself performing to stadiums was a shock. “It made me realise I wasn’t really cut out for that kind of thing. I’d have been hopeless, it taught me that!”

So, was his huge success with Robbie a vindication of taking a different path?

“The funny thing is, you have a lot of life, then you work with Robbie Williams and people ask you about that. Then you stop working with Robbie Williams and you go back to being the guy who left Duran Duran.”

He implies the association may have dampened his indie credibility. “I came back off that and we made a Lilac Time record and sold 500 copies. And it was like, ‘Oh, the good will that I had before seems to have strangely evaporated!’I don’t know whether… I suppose when you go and work with Robbie Williams, perhaps your next album isn’t going to be looked upon in the same way. And it certainly wasn’t.”

The Lilac Time Return

Which brings us neatly onto the new Lilac Time album, Return To Us. Did the band approach recording with a particular aesthetic in mind? “It always sounds the same because it’s me, my brother and my wife. My wife and I sing harmony together, and my brother plays the banjo out of tune. That’s basically all you have to know! And it’s great because we have a sound. The fact that it’s a deeply uncommercial sound that really hasn’t rocked many people’s boats is another thing.”

While writing began some time ago, the songs took on a new resonance with the turn of national events. “I wrote March To The Docks before the referendum and before anyone had said ‘Brexit’, so it’s amazing to have written a song that then becomes so resonant…”Sample lyrics include: ‘They’re changing the locks on our lives/ Every day another dream dies on us’. And then there’s the title track, with references to ‘changing a country’, ‘people making mistakes’ and civil war.

“Return To Yesterday was our first single in 1987 and we saw ourselves being quite a political band, to the point where I wrote a song called Let Our Land Be The One, where I’m furious about the privatisation of the water companies. So on this album, it’s like we’re singing the same old songs. ‘Come back, we’re still here!’– kind of blathering on about the injustices and the stupidity of everybody else on the right. “We live in very querulous times, it’s very mean-spirited.”

But if you’re expecting a dark album, the resulting LP is surprisingly optimistic in tone, even upbeat and celebratory on Return To Us itself. “Well, you’ve got to have a sense of humour, haven’t you? Otherwise, I mean it’s terrible because, having children, you look at them and they’re smiling, you’re smiling and then you turn on the radio…”

That softly-spoken voice can spew a considerable amount of vitriol upon the ‘morons’in charge, whether we happen to be talking about hapless politicians or record execs.

“You’re never going to understand why people thought that the other side was ever going to roll over, because, you know, when Thatcher was in we didn’t say, ‘Actually I think I’m going to give up being a socialist and become a complete c**t!’“You don’t do that, do you? You don’t change who you are.”

But put-downs that look savage on the page never sound so as he utters them. They come more from a state of bafflement that the world we inhabit can be so unbelievably bonkers. Still, he speaks fondly of the positivity and strength he finds in local community.

What Was I Thinking?

With the record’s release imminent, The Lilac Time will hit the road again later this year. “I enjoy playing now more than I ever have done, because I’m better now than I was. They don’t want some depressed guy who’s crippled with insecurity. I’m all about giving the people what they want, so I’ll be doing Kiss Me, Icing On The Cake… a little bit of tap dancing. But I play the old songs how I’d do it now, I’m not going to start playing the synth again.”

On the opening track of Return To Us, Stephen asserts: “I appreciate the past but I’ve never been nostalgic/ Life can be hard enough without all that bullshit.”He’s had some ups and his fair share of downs, but as he finishes his pint, he tells us: “I don’t look back at any of it with any sort of fondness, but I’m very happy that I’ve done it all.”

He doesn’t shy away from it either. “Nick Rhodes and I always thought we should go on tour with just two chairs, a table and a bottle of wine and some microphones, and just talk… No, I don’t think that’s going to happen, but I think we could fill theatres. Well, at least we wouldn’t have to play any music. That would be a great relief to everybody. Wouldn’t it be more interesting to be a raconteur than a folk singer?”

That said, this raconteur still has one thing yet to achieve. “I’m writing a book, I’ve been writing since 1978. Everything is in archive boxes, with dates on. I do have some funny stories. I haven’t told any of them today, obviously… No, I’m not going to tell you. It’s all in the book that’s never going to come out. It’s called What The Fuck Was I Thinking?. Every chapter ends with that thought… ‘Why didn’t I get off that plane and write with Madonna, what the fuck was I thinking?’”

Until that manuscript sees light of day – and let’s hope it does – there’s a wealth of riches to be enjoyed in Stephen’s ever-swelling catalogue.

So, who is the real Stephen Duffy? Weirdo (his words). Heritage act in the cave (his words again). Here’s another label for him to grapple with: national treasure. An unconventional one, for sure, but sometimes the best things are.

Click here to read more Classic Pop interviews