Classic Album: OMD – Architecture & Morality

By Mark Lindores | September 4, 2022

Merging the machinations of German electronica with warm Merseyside melodies and otherworldly choral samples, on their third album, Architecture & Morality, OMD struck the perfect balance between experimentalism and commercial appeal…

As Liverpool braced itself for a homecoming concert from its favourite musical son Paul McCartney on 15 September 1975, the city’s Empire Theatre played host to a sparsely attended show four days earlier as avant-garde auteurs Kraftwerk arrived in the city as part of their Autobahn tour.

Though the gig was far from sold-out, the chosen few that did attend ensured that its influence was far-reaching as the clued-up technophiles that formed the majority of the crowd left the venue convinced they had just witnessed the dawning of a new era of music and were inspired to become part of it.

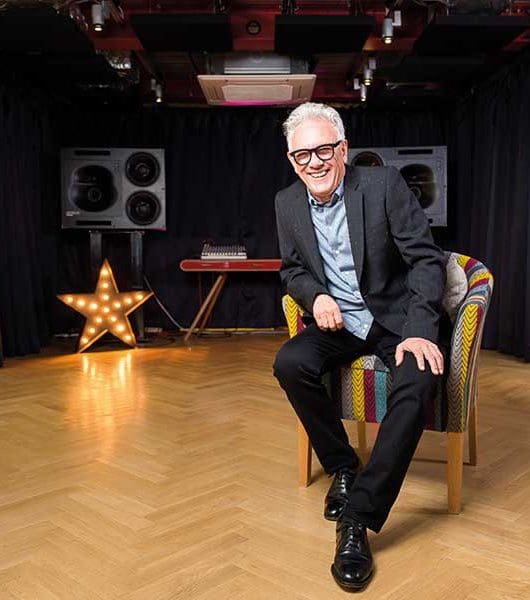

Among those embarking on a journey of sonic adventure courtesy of Düsseldorf’s alternative fab four were friends Paul Humphreys and Andy McCluskey, a pair of local musicians who had developed a kinship thanks to their shared love of the German synth-pop pioneers.

Although they had both played in a number of traditional rock bands, the pull of the industrial, minimalist soundscapes of their heroes led them to head in a different direction – with electronics as their foundation.

‘We always tried desperately not to repeat ourselves – we always tried to do something we hadn’t done before’

With finances and rehearsal space scarce, the duo was forced to improvise to make their ideas a reality. Like many of their friends in bands, the DIY ethos of punk was fundamental to Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark’s success.

Finding themselves as part of Liverpool’s thriving scene of the late 70s, they shared bills with Joy Division, Pete Wylie and Julian Cope, playing at local live music mecca Eric’s and Manchester’s Factory club, where they caught the attention of Factory Records’ Tony Wilson and namesake Carol Wilson.

Though he recognised the obvious potential of OMD, Wilson felt that Factory had neither the scope or the finances to support what he deemed to be a hugely successful mainstream pop act in the making. He signed them to a one-single deal to release their debut Electricity in 1979, purely to get them attention from the major labels.

As the majors began to close in on the band, OMD signed instead to Carol Wilson’s newly-established Dindisc label, an imprint of Virgin, feeling it would give them the artistic freedom of an independent, but the financial security of a major.

Upon the signing, Carol Wilson said: “OMD were a perfect fit for what I had in mind for Dindisc – they had a serious, artistic side with real depth, as well as a commercial, pop side.”

It was this duality that was key to OMD’s rapid success. Electricity was succeeded by a support slot on tour with Gary Numan and the release of a pair of albums – their eponymous debut and Organisation, released just eight months apart and spawning further hit singles in Messages and Enola Gay.

As their success continued to build momentum, Andy and Paul were fuelled by a sense of creative freedom that it was happening on their terms and without them having to conform in any way or compromise their artistic vision.

Entering the studio at the end of 1980 to begin sculpting their third album, the band (now expanded to a four-piece as drummer Malcolm Holmes and saxophonist Martin Cooper had become full-time members) did so with a confidence and liberation that allowed them to broaden their horizons both sonically and lyrically.

‘Having the confidence to make beautiful choral and textural pieces turned out to be the album’s ultimate strength’

“One of the things we always tried to do, particularly in the early part of OMD, was desperately try not to repeat ourselves – we always tried to do something we hadn’t done before,” Andy McCluskey told the BBC in 2006.

“So, having done a first album of sort of garage/punk/electronic and the second album that was a lot more dark and gothic and inspired by Joy Division, I think we were looking for a new direction and found a lot of influence in the emotional power of religious music.”

- Read more: Top 40 synth-pop songs

A major catalyst for the shift in direction happened by chance when a friend, and one-time member of the band, needed the use of a studio to work on a project which consisted of recording a choir and creating alternative ways of using them. He offered Paul copies of the samples by way of payment for studio time.

“Dave Hughes, a friend of mine, came round to our studio, and he’d done a choral session at Amazon Studios in Liverpool, making single note recordings of a choir but he didn’t have the facilities to piece them together,” Humphreys recalls.

“He said, ‘Can you help me make tape loops out of this choir? And if you do help me, I can’t afford to pay you for the studio, but I’ll leave you a copy of these tape loops and we can have a copy each.’ I put them all on a separate track of our 16-track tape recorder, identified which notes were which and made chords out of them.”

Left with a pile of vocal tape loops, Humphreys used them as a foundation and began constructing soundscapes and songs out of them.

Fusing the choral arrangements with commercial pop melodies and unconventional sounds not only gave gravitas to the historical and obscure references of their lyrics, it also lent an extra depth and dimension to their music, silencing critics of the synth-pop genre, which was still being hailed as style over substance due to its aversion to traditional instrumentation.

“Souvenir was the first song written for the album and I think that the discovery of mixing choral sounds with electronics, set the tone for the other pieces that followed,” said Paul Humphreys. “The textural sounds and inspiration came mainly from our discovery of a wonderful machine called a Millerton.

“This provided the sound beds and the atmospheres for the pieces and added together with our natural desire to experiment made the record a quite unique piece of work.

“A lot of the synth-pop element was directly from Kraftwerk and the melancholia came from Brian Eno, because we loved the textures and atmosphere of his work – it really was a merging of those two influences.”

Instilled with a will to not only avoid repeating themselves, but to always strive to be different from their peers, OMD were conscious of distancing themselves from what everyone else was doing. Shunning traditional love songs, they took lyrical inspiration from historical figures and events.

Structurally, their songs deviated from the traditional verse-chorus-verse format, often leading with prolonged instrumental sequences (Sealand) or replacing choruses with an instrumental synth hook (Souvenir), a feature which was becoming something of an OMD hallmark.

Stylistically, as the flamboyant New Romantics and Man Machine-esque Numanoids became synonymous as the perfectly made-up faces of synth-pop, OMD dressed in shirts and ties (and sometimes jumpers).

- Read more: OMD interview

Ultimately, their desire to be different worked in their favour. “Having the confidence to make beautiful choral and textural pieces at a time when others were at the other end of the spectrum making dance/pop music turned out to be the album’s ultimate strength,” says Humphreys.

It was whilst working on one of the final tracks for the record that the band came up with the song that would give the album its name, due to it being the perfect summation of OMD’s vision.

‘Architecture & Morality was a culmination of everything we had learned at that point about songwriting and about sound textures’

“The title was suggested to us by Martha Ladly, who was our sleeve designer Peter Saville’s girlfriend at the time, and she was in [fellow Dindisc signing] Martha And The Muffins,” recalls Andy McCluskey. “She had read Morality And Architecture – the book by David Watkin and we nicked it off her! I think she was going to write a song, but we stole it because we saw it as a metaphor for what we did.

“We had the ‘architecture’, which was the technology, the drum machines, the rigid playing, the attempt to break out of the box by playing specifically crafted sounds, and the ‘morality’, the organic, the human, the emotional touch, which we brought naturally.

“We weren’t trying to be Kraftwerk, we weren’t singing about being robots. We might have been singing about technology, or an oil refinery, or a telephone box, but we managed to imbue it, or distil from it, something emotional. It was a pretentious statement, which appealed to two 21-year-olds when we were asked to describe our music!

After Souvenir and Joan Of Arc both became Top Five hits in the UK, Architecture & Morality was released on 8 November 1981. Despite mixed reviews from the critics, the album reached No.3 in the UK and entered the Top 20 throughout Europe, including Germany where it peaked at No.8, a major achievement for the band considering the country’s influence on their music.

A further Top Five hit arrived in the form of the renamed Maid Of Orleans (The Waltz Joan Of Arc) and the album went on to sell over four million copies and is still revered as one of the seminal works of the synth-pop genre. It is also the record the band themselves are most proud of.

“Architecture & Morality was a culmination of everything we had learned at that point about songwriting and about sound textures,” Paul Humphreys says.

“Together, and separately, Andy and I have written some really good songs – before and after this album, but in terms of a collection of our songs, this hangs together the most successfully for me. It was as if the two albums prior to it were leading and directing us towards this piece of work – this was our finest hour.”

OMD: Architecture & Morality – the songs

1 The New Stone Age

Priding themselves on their ability to produce albums completely different from the one before, the jarring The New Stone Age was intended to fool fans into thinking the wrong record had been put into the album sleeve on first listen.

Though the jagged guitars sounded unlike anything OMD had put their name to previously, the unmistakable vocals confirm it to be the next step in the band’s evolution with Andy McCluskey turning in a desperate, anguished lead. Complemented by stabbing synths and chant-like backing vocals, the adventurous opener introduces a band firmly on the cusp of discovering their signature sound.

2 She’s Leaving

Although much more in tune with what is expected from OMD, She’s Leaving (the title of which was an homage to She’s Leaving Home by that other Liverpool songwriting duo Lennon-McCartney) had a troubled history. It had originally been written and performed while on tour in Canada and France, but, unable to record a version they were happy with, OMD grew bored of the song and left it unfinished.

It was only when they discovered an old version recorded at the Gramophone Suite that they tried again. While recording at the Manor, they simplified the song and slowed it down, resulting in a track that fans regard as OMD’s greatest lost hit single – a decision which the band admitted they later regretted, putting it down to being young and pretentious.

Dindisc wanted She’s Leaving to be released as a single, but OMD refused, claiming they’d be “exploiting” their album by pulling a fourth single from it.

3 Souvenir

A shimmering synth-pop masterpiece, Souvenir was the first track written by Paul Humphreys using the choral samples given to him by Dave Hughes.

With the samples pieced together to create a textured harmony and relayed over an irresistible synth track, the hook of which was featured in place of a traditional chorus (a structural signature OMD had also used on Electricity and Messages), Souvenir gave the band its joint highest UK chart position, tying with Sailing On The Seven Seas at No.3.

The success almost never happened, as Andy McCluskey initially hated the song, feeling it was too safe and saccharine and not the direction he felt Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark should be heading in. After six months of performing the track, he saw the magic of the song and realised its beauty.

4 Sealand

Having firmly established themselves as an acceptable gateway to synth-pop by taking their influences from experimental artists such as Kraftwerk and Brian Eno and distilling them into perfect, three-minute pop songs, the boys took artistic license with Sealand, a sprawling, seven-minute ambient work named after the RAF base on the Wirral, though the song itself is about an oil refinery.

The decision to name it Sealand came purely from the image the name conjured up as the perfect meeting place between land and sea. The haunting track unfolds at a slow, Eno-inspired pace, until a mantra-like vocal emerges at the six-minute mark from Andy McCluskey, delivering just a handful of impactful lyrics.

5 Joan of Arc

The first of a pair of tracks lamenting the French Saint, Joan Of Arc arose from the band’s aversion of writing traditional love songs, admitting they agonised over the very fact that the word ‘love’ was mentioned within its lyrics. “We always hated those kind of ‘I love you’ and ‘you love me’ kinds of songs,” Paul Humphreys said.

“Kraftwerk always sung about really unusual things and Brian Eno always sung about some very unusual topics and they were major influences so we kind of followed that line.” Released as the second single from the album in October 1981, Joan Of Arc reached No.5 in the UK singles chart.

6 Joan of Arc (Maid of Orleans)

The second track to be called Joan Of Arc, Andy McCluskey admitted that he wanted to release both singles with the same title just to confuse people but was dissuaded from doing so by the record label, instead releasing the single with the title Maid Of Orleans (The Waltz Joan Of Arc).

An epic track which was written by McCluskey on 30 May 1981, the 550th anniversary of Joan Of Arc’s death, it was written as a waltz, with mellotron, marching drums and bagpipes. Peaking at No.4 in the UK, Maid Of Orleans is one of the band’s signature songs.

7 Architecture & Morality

Having stolen the title from a friend that had expressed she was going to write a song called Architecture & Morality, the band moved fast to pen one of their own. “We wrote it in the Manor Studio in three days,” Andy McCluskey told the OMD newsletter in 1981.

“We decided to call it Architecture & Morality and then proceeded to throw onto tape everything ‘architectural’ and ‘moral’ that we could think of. Over the three days we gradually added and subtracted all manner of sounds until we had made something from all the noises.”

As well as being pleased with the finished track, which consisted of a sparse drum pattern, tape loops, swirling synths and filtered choir samples, the boys also loved the title, feeling it fitted the ethos of OMD and so decided to use it as the album title.

8 Georgia

The band had already written a song called Georgia for the album but they weren’t happy with the result and decided to shelve it. They were happy with the title, however, and wrote a new song keeping the name – a bouncy slice of electropop, which incorporated samples of dialogue, choral chants and one of the album’s catchiest hooks. The original Georgia was later revisited and reworked as Gravity Never Failed, which was included as the B-side to their 1988 hit Dreaming.

9 The Beginning And The End

A hallmark of many of the tracks on the record, The Beginning And The End is sparing with its vocals and heavy on the soundscapes. Dating back to an earlier incarnation of the group, VCL XI, Paul and Andy said that they had struggled to record a version of the song which they were happy with.

Though the album version was the best they had recorded to date, they later admitted in an Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark newsletter that they were still underwhelmed with the song and could have made it better.