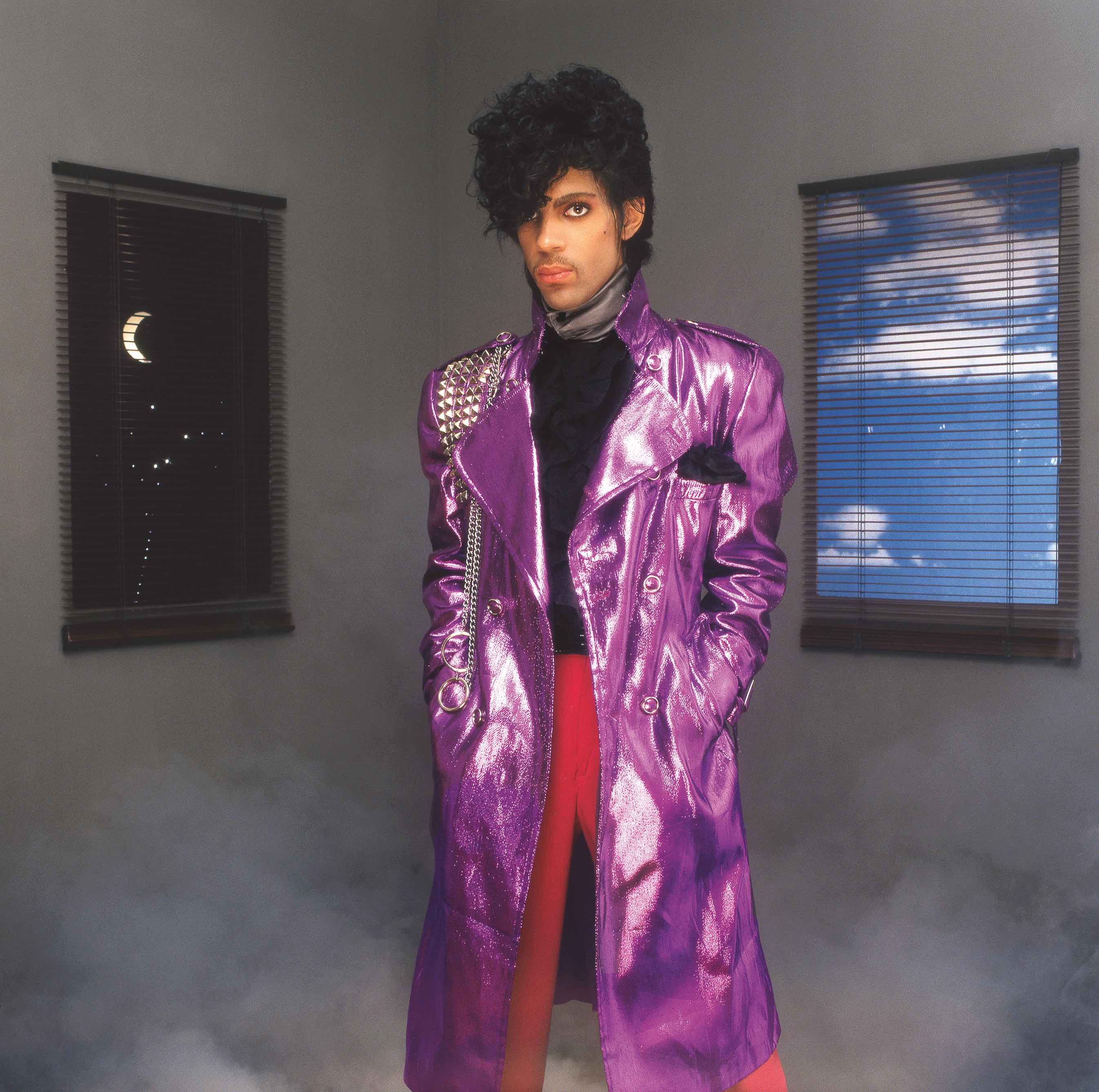

The Revolution Interview: Prince 1999 reissue

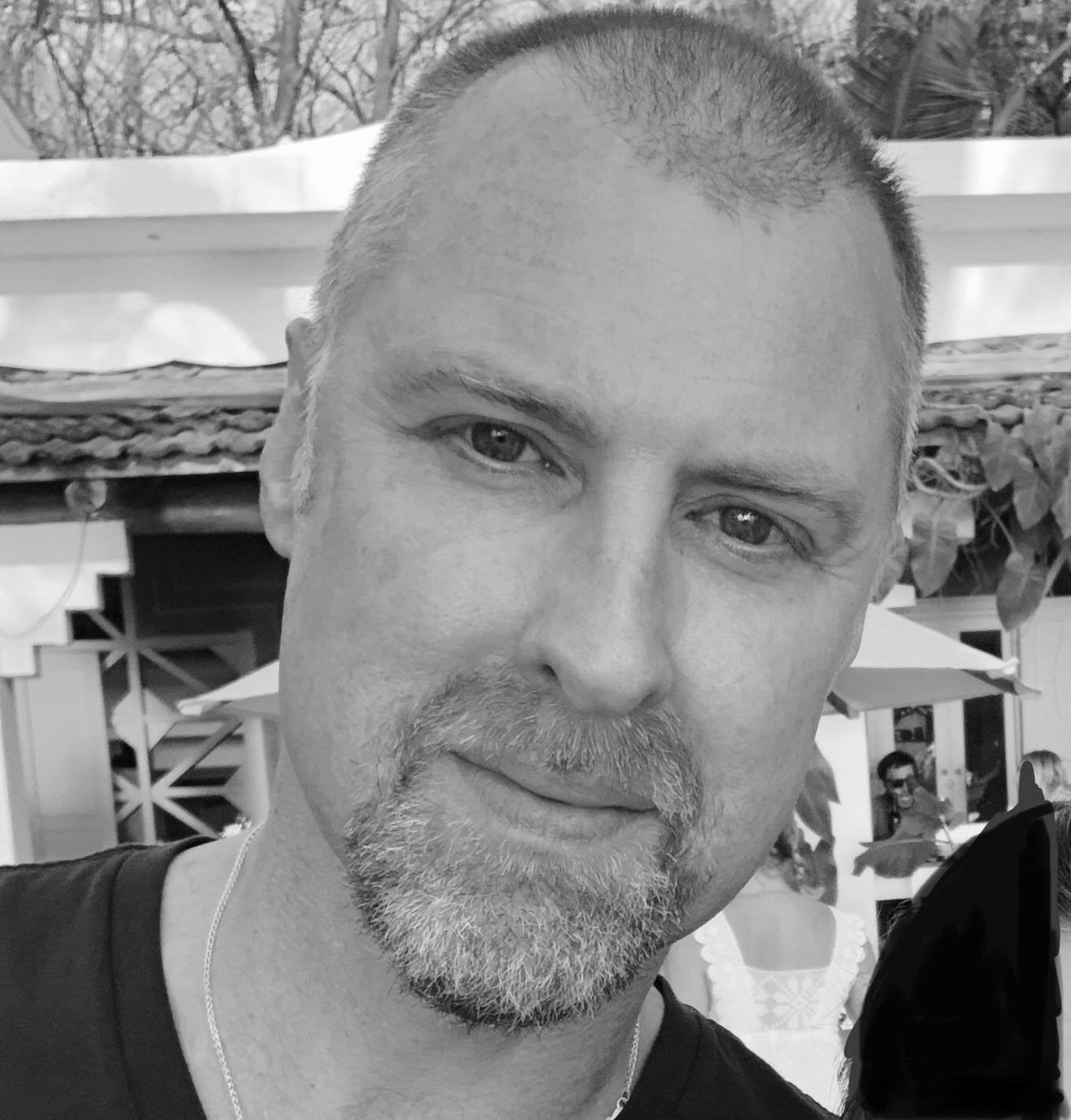

By John Earls | December 16, 2019

It wasn’t until the fifth Prince album – 1999 – in 1982 that the world really began to take notice of the High Priest of Pop. In 2019 we spoke to members of the icon’s inner circle to establish how he became a global superstar…

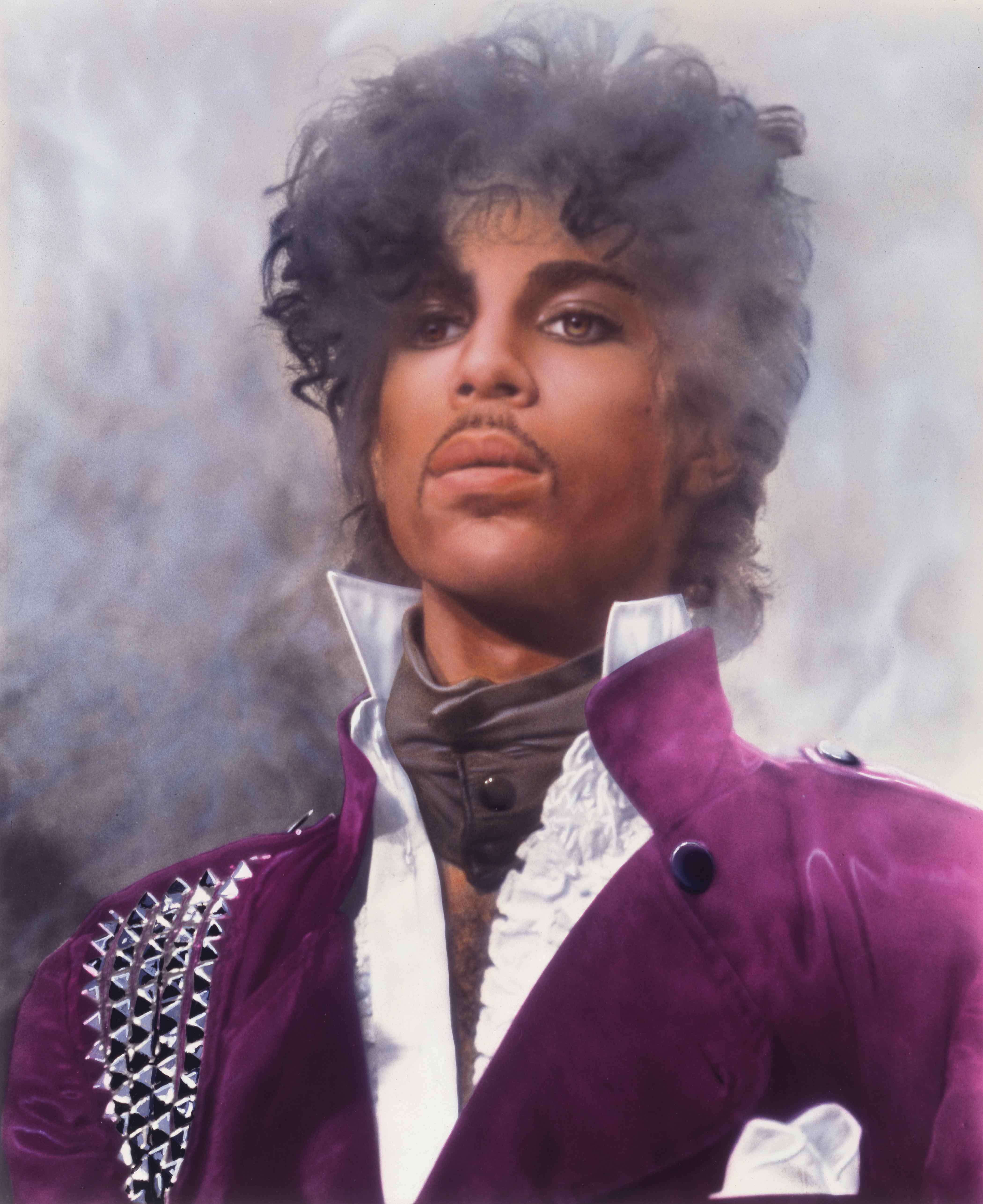

For anyone who likes their musical history linear, it’d be fair to say that The Rolling Stones played a key part in Prince going global – even if they weren’t aware of it at the time. Prince’s two shows supporting The Stones at the Coliseum in LA in October 1981 have gone down in folklore as “That time Prince got booed offstage”.

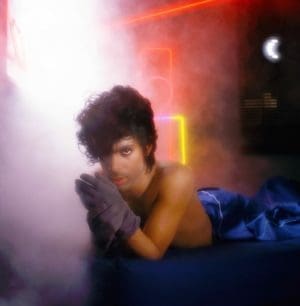

With Prince dressed in a see-through jacket and tiny black briefs, The Stones’ audience weren’t ready for a future superstar. He lasted just four songs, before the flying detritus got too much and he left during Jack U Off. Two nights later, he had to endure it all again.

“The Rolling Stones beatdown was a dark period,” recalls Bobby Z, the drummer who had played with Prince since they both left different Minneapolis schools in 1976. “When you play as young musicians you don’t in your wildest nightmares expect to be physically, mentally and audibly ordered off stage with objects and boos coming at you. It was very traumatic – and it happened twice.”

It was especially saddening for Prince, as he was such a huge Stones fan. Guitarist Dez Dickerson, who joined Prince’s band in 1979, says: “In all my time with Prince, I resonated most with his stated goal when I first joined – to be a black version of The Rolling Stones. He’d say to me, ‘I’m Mick and you’re Keith.’ That came naturally to me. Actually, the opening two-thirds of that first show with The Stones was stunning and memorable. The part that’s become folklore wasn’t how that show began. Challenging as it was, it was still one of my favourite experiences with Prince.”

Dickerson might have enjoyed trying to win over 94,000 angry Stones fans, but the opposition caused Prince to rethink his music altogether. “As dark and frustrating as the Stones experience was, what Prince did as a reaction was to write his way out of it,” says Bobby Z. “He created a fork in the road – for The Stones’ audience and rock radio, he created Little Red Corvette. And in one song, 1999, Prince encapsulated all the remnants left of the disco era.”

Jill Jones befriended Prince when she was a backing singer for Teena Marie, the support act on his Dirty Mind tour in 1980. They first worked together on 1999, when Jones could see Prince was determined to finally break through into the mainstream. “When Prince’s best friend André Cymone left the band as his bassist in 1981, he was on a different mission,” Jones explains. “He wanted to move away from the black charts and into the white charts, the pop charts. Accessing that new audience was a very creative time for him.”

Jill Jones befriended Prince when she was a backing singer for Teena Marie, the support act on his Dirty Mind tour in 1980. They first worked together on 1999, when Jones could see Prince was determined to finally break through into the mainstream. “When Prince’s best friend André Cymone left the band as his bassist in 1981, he was on a different mission,” Jones explains. “He wanted to move away from the black charts and into the white charts, the pop charts. Accessing that new audience was a very creative time for him.”

Lisa Coleman had joined Prince as pianist and keyboardist for Dirty Mind and saw his battle to break through. “Everything was just starting to take form around then,” says Coleman. “Prince’s management saw that what he was doing could be bigger, that he had the talent of a major artist. They’d sometimes push him to write that hit song – ‘That thing you play on the guitar all the time? That’s a hit: write it!’ They pushed him to that, but he wanted it, too. He wanted to be a great artist. At the same time, he was a guerrilla warfare guy who wanted to make his own rules.”

Famously prolific, Prince had so many ideas it’s no wonder he sometimes had to be reminded which of them were potentially gold. Even 1999 itself was remarkably casual. Jones recalls being woken up by Prince while with him at his house in Minneapolis to record her vocals, with Coleman driving over in the middle of the night having also been summoned. “I’d been asleep, and suddenly Prince was going, ‘Can you come and sing on this?’ like it was urgent,” says Jones.

Famously prolific, Prince had so many ideas it’s no wonder he sometimes had to be reminded which of them were potentially gold. Even 1999 itself was remarkably casual. Jones recalls being woken up by Prince while with him at his house in Minneapolis to record her vocals, with Coleman driving over in the middle of the night having also been summoned. “I’d been asleep, and suddenly Prince was going, ‘Can you come and sing on this?’ like it was urgent,” says Jones.

“I was in my pyjamas, threw on my fuzzy bunny slippers and made a cup of tea while waiting for Lisa. I guess your voice is still waking up if you’re woken up like that and has a different tone, so maybe there was method to his madness!”

As was standard for the pair, Jones and Coleman shared a microphone to record their vocals. “Mine and Lisa’s tones worked well together anyway,” says Jones. “I knew not to interfere with the main singer’s voice, but to add whatever my own tonal abilities were – those were always the best backing vocals.” Coleman is full of enthusiasm for Jones’ talents, laughing as she recalls the pair recording the song’s explosive “paaarty!” finale.

“Prince was encouraging me, going, ‘Come on, Lisa, this is your bit!’” she says. “I was a little shy, going, [timid voice] ‘Ooh, party, woo-hoo.’ Jill really has the power. She was kicking my ass, singing all these great licks, and she added the fire we needed. My voice is a lot dreamier.”

In seeking to make the album appeal to as wide an audience as possible, Prince made his message clear that he was here to dance as well as rock out. “The word ‘party’ is key to 1999,” says Bobby Z. “He might sound tongue-in-cheek, but ‘That’s right – party’ is an important line, as he’s cleaning up the mess left behind by ‘Disco sucks’. He’s saying, ‘It’s the end of the world, but we’re dancing to Prince and partying. It was a message of ‘This is your moment, so live it up.’”

In seeking to make the album appeal to as wide an audience as possible, Prince made his message clear that he was here to dance as well as rock out. “The word ‘party’ is key to 1999,” says Bobby Z. “He might sound tongue-in-cheek, but ‘That’s right – party’ is an important line, as he’s cleaning up the mess left behind by ‘Disco sucks’. He’s saying, ‘It’s the end of the world, but we’re dancing to Prince and partying. It was a message of ‘This is your moment, so live it up.’”

The drummer says the song was inspired by watching on tour the otherwise forgettable 1981 Nostradamus documentary The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, voiced by Orson Welles, which predicts the apocalypse will happen in 1999. “All these movies we saw on VHS on the tour bus inspired Prince,” says Bobby. “The Idolmaker, an amazing film about Fabian, inspired Prince to create The Time. A huge part of creating Purple Rain was Quadrophenia – the different styles of clothing for mods and rockers fascinated Prince. We were immersed in culture.”

Maybe so, though Prince wasn’t above less artistic pursuits on tour. “Prince was big on Mattel Intellivision, which was infinitely better than Atari but not marketed so well,” states Dickerson. “Prince and I got locked in battles on Super Pro Football. We’d have running tournaments, getting to the point where we almost couldn’t wait to be done with the show, so we could get back on the bus and resume playing. Prince hated to lose, but it took him two tours to finally beat me. He got crazy about it.”

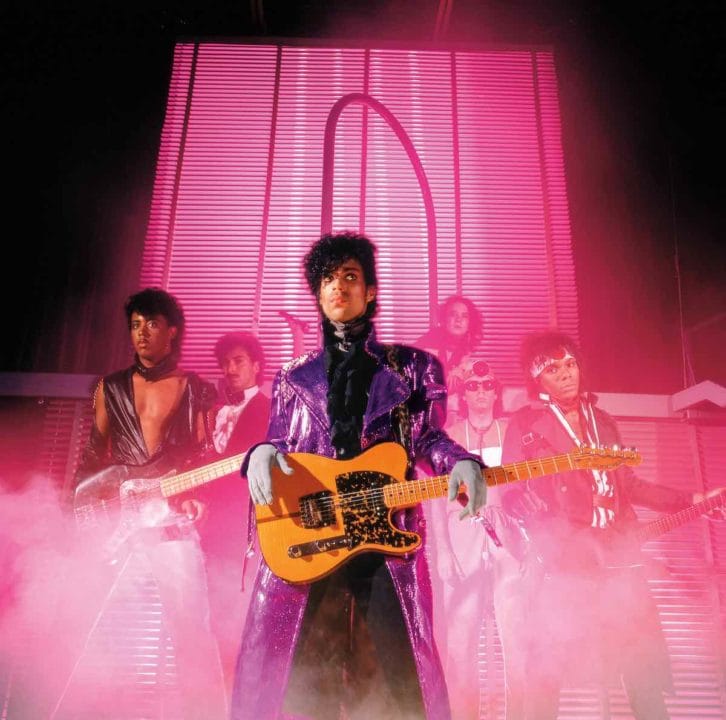

According to Bobby Z, Prince filmed mockumentaries “and all kinds of fun stuff” as soon as he got his first camcorder, but he also began filming band rehearsals. “Filming became one of Prince’s tools to get perfection,” says Bobby. “You learned that nothing got by him, because he watched that stuff 24 hours a day. I learned what my head and hands were doing for every stroke of the drum kit. All this gave him a bug to do more, be more creative with video. We became really good at rehearsing our performances for the videos.”

According to Bobby Z, Prince filmed mockumentaries “and all kinds of fun stuff” as soon as he got his first camcorder, but he also began filming band rehearsals. “Filming became one of Prince’s tools to get perfection,” says Bobby. “You learned that nothing got by him, because he watched that stuff 24 hours a day. I learned what my head and hands were doing for every stroke of the drum kit. All this gave him a bug to do more, be more creative with video. We became really good at rehearsing our performances for the videos.”

The strangest of the album’s promos was the sexually explicit film for Automatic, which was never going to be shown on MTV. “Prince had lost his provocative shock value a little by then,” Jones believes. “He wanted to shock everyone a bit. The bondage and domination was art imitating life. Automatic was funny because, like 1999, it was another twisted, creepy girl song from Lisa and I. And I’m crying in it again – it’s so strange, Prince always had me crying on records! Prince wanted me to be very mysterious in his videos, like, ‘Who is this blonde woman showing up in the middle of everything?’”

The new 10-LP boxset for 1999 shows just how carefully Prince selected the 11 tracks for the original album. As well as B-sides and alternative takes, the box features 17 songs recorded at the time which had never officially been released, spread chronologically across two discs.

Michael Howe, the manager of Prince’s estate who compiled the set, explains: “The breadth and depth of what Prince was experimenting with at the time is remarkable. When you listen to the original 1999 album, you hear how coherent it is. But some of these other songs are prime material, too.”

Howe was Prince’s final A&R representative before managing his estate, mentioning Feel U Up, LGBTQ anthem Vagina and a “vulnerable, playful” alternative take of International Lover as personal favourites. Would he have fought to have those on the album if he’d been Prince’s A&R in 1982?

Howe was Prince’s final A&R representative before managing his estate, mentioning Feel U Up, LGBTQ anthem Vagina and a “vulnerable, playful” alternative take of International Lover as personal favourites. Would he have fought to have those on the album if he’d been Prince’s A&R in 1982?

“If I was Prince’s A&R back then, I’d have been very careful about volunteering an opinion in any forceful way on the creative side,” he laughs, adding: “I think his decision-making was remarkably sound. There are a couple of songs in the bonus material that are very special, but Prince’s overall process can’t be questioned.”

There’s a live album from Detroit and live DVD from Houston in the package, with only one rumoured recording proving elusive: an early version of Raspberry Beret apparently made three years before it appeared on Around The World In A Day. “I think Prince either wiped the original, or overdubbed so many elements on the final recording there’s no way to pick apart the DNA of what the 1982 version was,” Howe posits. “That’s a bummer, as I’d certainly love to hear the 1982 version and share it with the world.”

At the same time as recording 1999, Prince was writing and producing the debut albums by The Time and Vanity 6. “Prince was becoming the master of his own three-ringed circus,” explains Bobby Z. “Seeing them together was like you were being attacked by an army from Minneapolis, but really it was all this one guy.”

At the same time as recording 1999, Prince was writing and producing the debut albums by The Time and Vanity 6. “Prince was becoming the master of his own three-ringed circus,” explains Bobby Z. “Seeing them together was like you were being attacked by an army from Minneapolis, but really it was all this one guy.”

Coleman adds: “The character Morris Day plays in The Time was a facet of Prince’s personality. He’d fool around, look down his nose the way Morris does… It was very funny, but a part of his personality Prince decided he couldn’t use in his own work. Prince was great at distilling his personality, breaking apart pieces of himself and giving them to others so he could focus on what he wanted in his own music.”

Prince watched The Time every night. “Prince created a competitive environment between his bands,” says Jones. “He left frustrated with his own band more often than with The Time. They had a magnetism and all knew each other’s movements. I don’t recall many times when Prince’s band would watch The Time, and that was a big tell – he’d come back from seeing them and try to pump up his own band. But The Time were blazing. They burned Prince many nights on tour, and he knew it.”

Prince would sometimes party after a show, but he’d watch all three acts’ performances back on video early in the morning. “He’d either give you notes or recreate something in soundcheck he wanted to try out in the show that night,” says Jones. “It kept people on their toes. That rivalry and competition was good for him.”

It kept Prince on top, but Bobby Z couldn’t keep up, admitting: “I was on my bunk on the bus at 4am and all of a sudden I’d see Prince’s face in my bunk, saying, ‘You missed a cymbal on something.’ I went to his management and said, ‘Prince is a rock star now. Will you please get him his own bus?’ He was a little overwhelming, but loved to come back and be with us.”

The 1999 tour was Dickerson’s farewell. He missed the more freeform nature of Prince’s early shows. He’d also discussed getting Prince’s help to go solo when the time was right, rejecting an appeal to stick around for three more years to record and tour what would become Purple Rain. “People will often ask, ‘How could you walk away from the fame and money?’” says Dickerson.

“But if you’ve got contextual blues, none of that matters. My epiphany was, ‘I wouldn’t want to be around me right now, and I’m not doing my friend any favours staying in his band when I’m just miserable.’ It was time to go. I was able to make sure I gave my best at the shows, but it became more of a struggle. Prince and I had conversations about finding a way through, but it had become too slick for me.”

At least Prince had the perfect solution: he’d snuck the name of The Revolution onto 1999’s artwork in backwards writing and knew how to develop them. “The Revolution were an alternate society,” says Coleman. “We were these hippy purple people. Prince saw us as a cult, an alternative movement. His records were all-inclusive, mysterious, sexually provocative. He stirred people up and connected to a whole lot of people who needed that.” It meant the purple reign was just beginning.