Marilyn interview: “People want me back. That’s amazing”

By John Earls | March 4, 2023

For a singer who only released one album, Marilyn has made an indelible mark on pop culture. In 2016 he returned a new single, Love Or Money, produced with his fellow 80s troublemaker Boy George. That year, he talked about his comeback to Classic Pop…

For a singer who only released one album, Marilyn has made an indelible mark on pop culture. In 2016 he returned a new single, Love Or Money, produced with his fellow 80s troublemaker Boy George. That year, he talked about his comeback to Classic Pop…

Marilyn is looking well. It’s important to state that right away because, in the 13 years since he was last seen in public – as a contestant on Channel 4’s reality hairdressing show The Salon – it’s been no secret that Marilyn had reverted back to heroin.

When Boy George was arrested in 1986 for heroin possession, so too was his former housemate – well, squatmate. The charges against Marilyn were later dropped, but he endured a near-constant battle with heroin until finally getting himself clean two years ago.

Now that he’s “enjoying being alive”, Marilyn is not only looking great, but sounding great, too. He was often unfairly dismissed in the Eighties as a Boy George copycat, but Marilyn is someone who knows his way around a groove, as one listen to the booming, contemporary reggae pulse of comeback single Love Or Money will attest.

Sat on an armchair in his publicist’s office, Marilyn is more solid than you’d expect. His blond hair is neat and neck length; he’s wearing a black T-shirt festooned with necklaces, and looks almost like the lead singer of a glam metal band.

He’s quick to laugh, and when he does so it’s a delighted cackle, the sound of someone who’s waited 30 years to share his gossip and doesn’t give a damn who’s listening in. As Marilyn says of himself: “I f***ing stand for something, and I don’t think there’s a lot of that going on right now.”

But he needed to be clean before he could remind the world of his talent. “I wouldn’t be sat here talking to you if I wasn’t clean,” he insists. “When I wasn’t clean, the last thing I’d want to do is sit and chat to people, or talk about anything.

“I’d close the curtains, I wouldn’t care if it was day or night. I didn’t care or want to know what was going on outside. My life would be in my room.”

So what changed? His response is matter-of-fact. “I was bored of hospital visits and near-death experiences.” A small laugh. “They get boring after a while, especially when you can’t take the last step and just die. I’d think ‘Oh, what’s the point?’”

Since his last spell in hospital in 2014, Marilyn is finally ready to work on music again in earnest, writing and producing with Boy George and their friend John Themis, with a full album to follow Love Or Money.

“I don’t know if I’m excited to be back making music,” he ponders. “But I’m definitely excited to be clear-headed and healthy. And it’s exciting to recognise that people love me, because now I finally have the ability to love them back.”

Knowing that people care about his return has been the biggest revelation since he gave up drugs, he says. “I never put a lot of music out,” he allows.

Knowing that people care about his return has been the biggest revelation since he gave up drugs, he says. “I never put a lot of music out,” he allows.

“But people remember who I am. At the time, that worked against me. I was a lot for people to take in, and I was accused of being style over substance. But now, music is all style and no substance.” Another laugh. “So, finally, I’m ahead of the game!”

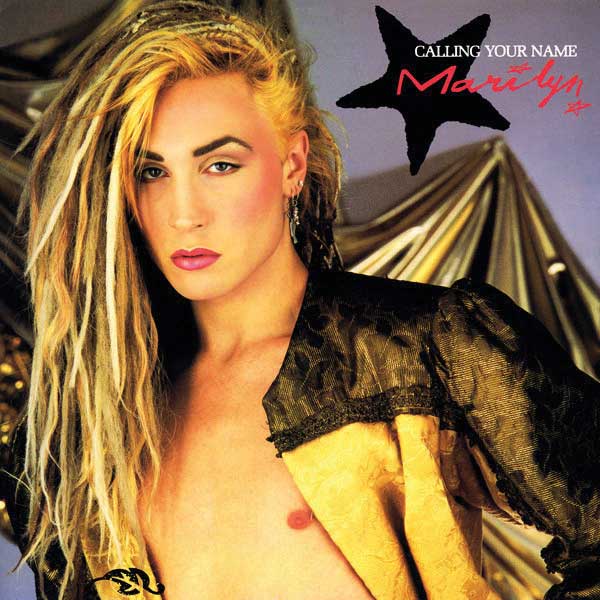

Marilyn was certainly hard to forget when he appeared with Calling Your Name in 1983. A more extreme, less cuddly figure than someone with Boy George’s mainstream appeal, Hertfordshire-raised Peter Robinson had taken the Marilyn nickname he was mockingly given by school bullies and used it to emphasise his androgynous beauty.

He may have only been 20, but Marilyn had already worked in LA as a PA to soap star Terry Lester, as well as appearing in Derek Jarman’s short film Broken English and Eurythmics’ Who’s That Girl? video.

- Read more: Top 20 double A-side singles

“I’d done a lot of life already,” he smiles. “I felt really old when Calling Your Name came out. I thought I knew everything. But that success was a lot for a 20-year-old to cope with. There was no time to process anything, it was just next, next, next, pressure, pressure, pressure.”

It didn’t help that Marilyn was battling against being marketed as a clone by Phonogram. “They wanted me to be the next Boy George, and that was never going to work for me,” he sighs.

“George was my best friend, don’t forget. So I was having to say ‘You want me to have a career as being like my best friend? Do the same kind of music as Culture Club?’

“Culture Club were great, but it’s not my kind of music; I wanted something with more rhythm. The only reason to copy something was money, and that’s bullshit. It was like being a puppet.”

Having met in the New Romantic epicentre of Blitz, Marilyn and George began sharing a flat off London’s industrial Euston Road – the same street where his publicist’s office is today. “We used to be competitive and quite bitchy. We were all over the shop, really.”

What was the squat like? “No electricity, and we only had an outside toilet, which didn’t have a roof on. People would lob stuff at us from their upstairs into the toilet if one of us used it – cups of coffee, washing up. I don’t remember us ever eating as much as a bag of crisps there, come to think of it.

“We’d wait for the milkman to deliver at 5am, then steal all the milk off the doorsteps. We’d live off 50 pints of milk a day. And we lived in that squat for four or five years.”

No wonder Marilyn looked so hungry for success when he performed Calling Your Name on Top Of The Pops. He seemed a born star, but those record company battles made it hard to focus on the actual music.

By the time his sole album Despite Straight Lines appeared in 1985, most fans had moved on.

At least Marilyn got to have a blast making the single Baby U Left Me with Was (Not Was) in Detroit. “Their singers were so talented,” he enthuses. “Hearing people like Sweet Pea Atkinson, I’d be in the studio going ‘Oh my God, wow!’

“Don Was was funny, too, and great at getting the best out of people. Too many people around me were telling me how I should sound, but Don wanted to figure out how to get the song sounding how I wanted.”

How does Marilyn feel about Despite Straight Lines today? “When I was recording it, I was never happy. I always thought it could be better. If my songs came on, I was always ‘Oh, noooo’, as I could only hear the imperfections.

How does Marilyn feel about Despite Straight Lines today? “When I was recording it, I was never happy. I always thought it could be better. If my songs came on, I was always ‘Oh, noooo’, as I could only hear the imperfections.

“But now, whether it’s with age or distance and time, I think ‘Woah, I did a good job!’ And knowing that people want me back, that’s amazing.”

But before Marilyn came to that acceptance, he did try – briefly – to fit in. He even tried a steady job, but that ended in farce. “Trying to fit in was an exercise in frustration,” he says. “You get a lot of people looking down on you, and they’re taking delight in not giving you access to normality.

- Read more: The Story Of The New Romantics

“I asked for a job in Tesco, saying ‘I’d like to stack the shelves, please’, and the response was (haughty voice): ‘You? Work here? Oh, no.’ And I said ‘OK, f*** you. You stack ‘em! I’ll do what I want to do, then.’” He can laugh about it now, but the image of someone who sang on Band Aid being rejected by Tesco is horrible.

Around the time of The Salon, Marilyn had a musical comeback in 2003 with the single Hold On Tight, but he admits it was a half-arsed job.

“People would always ask me when I’m doing more music, but I wasn’t in the right headspace. I’d shrug it off, go ‘Nerrr, maybe…’ But I eventually thought ‘Oh, there must be something I can give.’

“So I got a friend to do three songs and press a few copies. It was a very small run, basically to shut people up. ‘You want new music? Here, have that.’ It wasn’t exactly ‘Here’s my new work, world!’”

That’s taken until Love Or Money, which sees Marilyn and George working together more harmoniously than ever. “We’re still mental, but in a much more aware way,” Marilyn cackles.

“We can still go back to our old ways, but we’ve grown up enough to say ‘No, I don’t want to do that’ if the other one is being annoying. It’s just experience, really. We never consciously decided ‘Let’s not do that anymore,’ but we do say ‘Er, that’s old behaviour, can you stop?’”

The next single is finished, and there are six other Marilyn and George songs in various stages of completion. The pair’s main bone of contention now is over listening to music. “I constantly listen to music,” Marilyn explains.

“When I go to George’s house to write, I try to put music on. He’ll be ‘Turn that off!’ and I’ll tell him ‘I can’t believe you don’t listen to music.’ George says ‘I just don’t listen to music when I’m working on it.’ ‘Well, I do…’”

If the other songs are of the same quality as Love Or Money, Marilyn’s second album will be worth the 32-year wait. But is the world ready for him at last?

“It feels like it must be, because I’m here doing it,” he responds. “But, yeah, I feel loved and recognised for what I stand for. There’s a lot of talk about ‘Be who you are, be different, think outside the box, don’t be controlled’, yet there’s a lot of manipulation going on.

“I’m not part of any tribe. The world is my tribe. I’m not part of any one group, I’m just me in the world. And that’s what I stand for: individuality, free-thinking. The world needs to be reminded that you don’t have to be a robot and do what everyone else is doing. There’s a place for that, but I’m at the opposite end of the spectrum.”

Marilyn has earned the right to be so forthright. How many other musicians were so out there, even in such a haven for misfits as the early Eighties?

How many have endured such a long time out of the public eye, only to return in such ready humour? And how many more have had rubbish thrown at them while sharing an outside toilet with Boy George?

Marilyn has the air of someone who’s about to give the world what for all over again. Tesco’s loss is music’s gain.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!