In the 80s, Hollywood turned its back on orchestral film scores in favour of jukebox-style compilations that sold in their millions – but did commerce win out over art? By Will Simpson

The relationship between movies and music is long and intertwined, from the live soundtracks that were performed to accompany silent films to the stirring orchestrations of the golden age of Hollywood. Just as a decent meal requires a sauce of some description, so films need music.

For decades, Hollywood had contracted out its supply to individual composers and many gained significant fame from it, their names becoming synonymous with certain cinematic genres. Ennio Morricone will forever be associated with the innovative way he created drama for Sergio Leone’s westerns. Likewise, John Barry will always be linked to the James Bond franchise.

But the 1980s saw the decline of the specifically commissioned score and the rise of the compilation soundtrack. Within a few years virtually every blockbuster sported one, from Flashdance to Footloose, Ghostbusters and The Goonies to the Rocky series. Indeed you can trace the shift through Sylvester Stallone’s boxing franchise.

Its first two instalments featured Bill Conti’s largely instrumental score. By 1985, the Rocky IV soundtrack is a star-encrusted compilation featuring James Brown, Kenny Loggins, Go West and Gladys Knight.

Expense was, of course, a major consideration here. Why commission a composer, hire an orchestra and block book studio time when you could farm the whole thing out to a record label, which could use existing material at a fraction of the price? Plus with pop music now the dominant medium of expression amongst international youth, they just seemed more modern, accessible, fun even.

Though the word had yet to be coined there was a synergy to this. Rather than a work of art in itself, the compilation soundtrack was a musical advert for the movie. And for the record companies, the likelihood was if the movie was successful, they would bag a hit single, or better still, successful album, on the back of it.

The videos to those singles were, essentially, free trailers. Every summer the upper end of the singles charts would be populated with movie tie-ins – Irene Cara’s Flashdance (1983), Axel F by Harold Faltermeyer (Beverly Hills Cop, 1984), Starship’s Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now (Mannequin, 1987). The most successful of these created a kind of feedback loop between movie and song, a trend that reached its apogee in the summer of 1991 with Bryan Adams’ 16-week reign of terror at No.1 with Everything I Do (I Do It For You) from Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves.

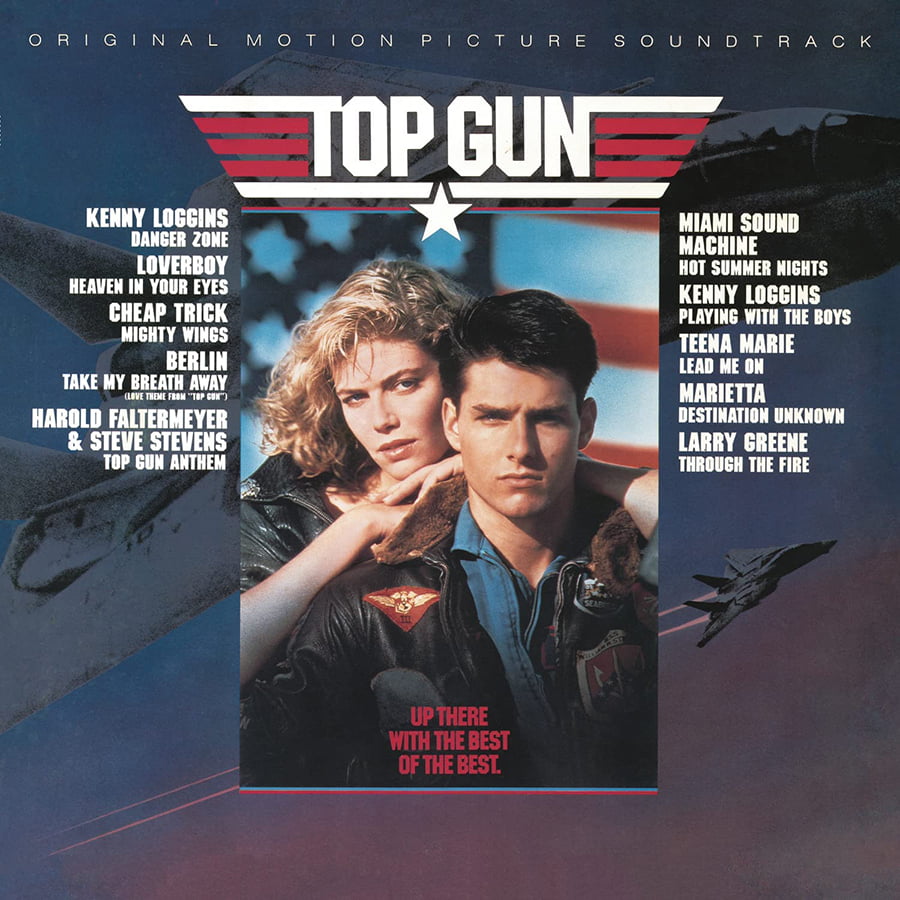

And comp soundtracks often did pretty good business themselves. The Top Gun soundtrack went double platinum in the UK alone. The Beverly Hills Cop soundtrack went to No.1 on the Billboard chart, whilst Footloose’s went nine times platinum in the US.

That said, even an expertly-compiled soundtrack couldn’t rescue a dodgy film. How many of us were hooked in by the romantic beauty of Bowie’s Absolute Beginners only to discover that the accompanying movie stank like a pair of week-old socks?

There were two turning points in this trend. The first was The Graduate in 1968. Featuring Simon And Garfunkel songs that had already been issued on their first two albums, it was the first time that ‘pop’ music had been used in a mainstream Hollywood film outside specific artist-led flicks like A Hard Day’s Night. The soundtrack sold more than two million copies and picked up a Grammy.

Read more: Debbie Harry on film

Read more: Who’s That Girl – Madonna on film

Then a decade later came Saturday Night Fever. A double album of Bee Gees songs with a smattering of disco hits from around the same era, it shifted an incredible 40 million copies worldwide: the biggest-selling soundtrack of all time at that point. Previous holders of that title had been cast recordings of musicals (The Sound Of Music, West Side Story et al), but Saturday Night Fever was as gritty as any 70s kitchen sink drama. Hollywood lifted its nostrils and sniffed the possibilities.

But whilst the trend undoubtedly got cash registers ringing did it produce better soundtracks? Or even better pop? So many of the comp soundtracks were little more than merchandise. Often they would contain one or two marquee names, alongside a host of lesser lights that the record label often didn’t know what to do with but stuck on there in the hope that something might land.

Sometimes it did – Go West gained a commercial second wind through the inclusion of The King Of Wishful Thinking in Pretty Woman. But even a place on the Beverly Hills Cop soundtrack couldn’t rescue Junior Giscombe by 1984. Did her inclusion on the Top Gun soundtrack make any difference to the career of Marietta? Who? Exactly.

Some soundtrack comps hedged their bets slightly. Doubtless many Madonna fans purchasing the Who’s That Girl album weren’t thrilled to find that fewer than half the tracks were by the Queen of Pop, the rest being filled by such distinctly unroyal artists as Duncan Faure and Michael Davidson.

Then there were the hybrid soundtracks that fell between two stylistic stools – Back To The Future’s mixed original songs by Huey Lewis And The News, Eric Clapton and Lindsey Buckingham with an orchestral score by Alan Silvestri. Most punters skipped the album altogether, and bought The Power Of Love single instead.

At least Huey Lewis had other hits. Movie comps had a habit of throwing up one-hit wonders forever associated with/tarnished by that one film: New York hip-hop duo Partners In Kryme traded in whatever cred they might have once had when they took the Turtle dollar. Meanwhile, Berlin were a hip LA synth outfit that lost any claim to coolness once Take My Breath Away became a worldwide hit. Its huge success caused ructions within the band and they split not long afterwards.

Despite the wave of comp soundtracks, the traditional craft of the movie composer didn’t wither away entirely. Some of the biggest movies of the decade sported orchestral soundtracks – ET: The Extra-Terrestrial, the Indiana Jones franchise (John Williams) and Aliens (James Horner) were the work of Hollywood veterans still at the top of their game.

During the decade they were joined by figures like Brad Fiedel (The Terminator) and Vangelis, whose synth-based approach worked perfectly for Blade Runner and, more surprisingly, Chariots Of Fire.

What did the 80s compilation soundtrack produce apart from a lot of old CDs in charity shops? Not much, I’d argue. If soundtrack curating is an art then it’s fair to say it didn’t come into its own until the following decade.

Quentin Tarantino was the game changer here, showing a crate-digger’s nous at how just the right blend of retro soul, half-forgotten hits and obscure 50s rock could be marshalled to provide something indisputably cool. In contrast, by the mid-90s soundtrack comps were starting to look like lazy corporate sell-outs. Not cool and – to an increasing number of punters – not worth the cover price either.

So movie soundtracks evolved once more. Come the 21st century many old school film composers – Hans Zimmer, Alan Silvestri and John Williams – are still working in Hollywood. Some of the newer faces in film scores have moved over from the world of pop. Danny Elfman is best known these days for his work on many of Tim Burton’s films and, of course, The Simpsons. Not bad for the ex-singer with LA new wavers Oingo Boingo.

In recent years he’s been joined by Clint Mansell, former frontman of Pop Will Eat Itself (Moon, Black Swan), ex-Red Hot Chili Pepper Cliff Martinez (Only God Forgives, Drive) and Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood (There Will Be Blood, The Master).

And the 80s comp soundtrack? Perhaps its fate will be to one day be revived as 20th Century kitsch; a memento of the days when record labels and movie distributors carved up the world between them and punters would cheerfully part with £15 in exchange for one big hit and a whole heap of filler.

Read more: The story of MTV

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.