Producer Gareth Jones. Photo by Doug Dreger.

Music producer Gareth Jones has worked with some of the biggest names in synth-pop, including Erasure, Depeche Mode, Wire and John Foxx. In 2020, he talked us through his stellar career…

Vince Clarke has buddied up with many producers in his life, but there are some he returns to again and again. One of those is Gareth Jones, whose name first crops up in the Erasure story in 1989 as the co-producer of the band’s fourth album Wild!.

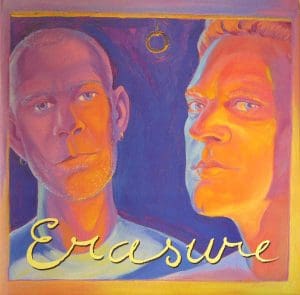

From here, he’d sprinkle his sonic magic over another six Erasure LPs, from 1995’s Erasure to 2013’s festive fave Snow Globe, with a clutch of remixes in between.

“Thirty years we’ve been working together,” Jones tells Classic Pop down the blower from his studio in France. “There’s nothing in my working life comparable to that.”

It’s not hard to figure out why exactly Vince Clarke was drawn to the 66-year-old electro-pop maestro.

Like Clarke, Jones was bewitched by music and the tech behind it from an early age, lapping up Beethoven and Bach and later The Beatles and Pink Floyd at the same time as he was indulging his inner geek, “mucking about with tape recorders”.

“I was fascinated by the sounds of halls and churches and big string sections,” he tells us. “I loved classical music as a teenager, but as my horizons expanded I discovered rock and pop.”

It was the work of George Martin in particular, he says, that would be the biggest influence on him as a music-hungry teen, particularly Martin’s trailblazing production on Revolver and ‘The White Album’, helping open Jones’ eyes as to what wonders the recording studio was capable of.

“Clearly there was more going on in these records than a band playing live in the studio,” he says. “Also, I was fascinated by the art of tape recording. So I was editing tapes, recording my mates at school and stuff with one microphone.

“It was somehow in my DNA, you know. And as soon as I got the chance to work in music studios with musicians then it was just like 24/7 365. I just felt like it was my calling, really.”

After training at the BBC, Jones got his break working as a sound engineer at Pathway in north London, a poky eight-track recording studio founded by producers Peter Ker and Mike Finesilver in the 1970s.

“I remember [producer and songwriter] Clive Langer coming in with Madness and we recorded The Prince and its B-side [Madness],” Jones remembers.

“And that was a great experience, and it got me more into studio manipulation because Clive had a [Roland] Space Echo that made really wonderful trippy echoes on things.”

Producer Gareth Jones. Photo by Doug Dreger.

It would be shortly after that, however, that Jones would have his first experience working on purely electronic music.

John Foxx, the then-recently departed Ultravox frontman, had booked into Pathway to record his debut solo album Metamatic, and approached Jones for his input. He remembers Foxx playing Warm Leatherette by The Normal, and being blown away by it.

- Read more: Top 40 Vince Clarke songs

“It was one of my introductions to modern British electronic pop,” he enthuses, more than four decades later. “There were a lot of influences going on on that record.”

Though unable to play any instrument himself, Jones says that his first explorations in electronic music proved “amazingly liberating”: “The Musician’s Union and general musos adopted machines a little bit later, but at the beginning, at least to the Musician’s Union, it felt like machines were cheating,” he points out.

“But for a lot of us, it was a liberating force. It allowed us to, dare I say, express ourselves without having the chops to be able to play amazing guitar or amazing keyboards, we could still make records that people would dance to or want to listen to.

“So this combination of tape and the emerging digital technology was very exciting to me, it allowed us to do shit we couldn’t have done otherwise.”

Call of the wild

The following years would see Jones involved in some of the defining albums of the era, including Depeche Mode’s Some Great Reward, Black Celebration and Construction Time Again, Einstürzende Neubauten’s Halber Mensch, Wire’s The Ideal Copy, the second Tuxedomoon album Desire, and a trilogy of Edgar Allen Poe-inspired albums by avant-garde diva Diamanda Galás.

“Diamanda knew Andy Bell somehow, and so told him I might be a good fit,” Jones recalls of how Erasure first entered his life.

“I helped on a lot of the vocal production on that record as well as the mixing, while Vince was in another studio at the time with the other co-producer working on the music.”

Jones says that he only met Clarke ‘occasionally’ during the making of Wild!, and that it was only on later records that he began working more directly with Clarke on the music side.

Surely it was a meeting of minds? Wasn’t there a tendency for both Jones and Clarke to kick back and geek out over their love of music tech with Andy on the other side of the studio, rolling his eyes?

“There’s an element of that,” he laughs. “Certainly at the start, I guess. But everyone’s all grown up now. Andy’s very interested in the studio these days. I’ve done a couple of remixes with him recently where he was very creative and hands-on about how they were put together.

“Obviously Vince is one of the grandfathers of British electro-pop, so obviously he’s a total geek, but I don’t know if he’s got much time for geeking out. I’m more likely to have a chat about how our lives are going over a glass of wine or a beer.

“There’s definitely a geek element there but when Vince is working he’s very focused and down to earth. He just gets on with the job. There’s not a lot of, ‘Shall we try this synth?’ or ‘Shall we do this?’ He just goes in there and makes his art.

- Read more: Pop Art – Vince Clarke

“With other colleagues I can get drawn down the geek rabbit hole more easily, but in my studio relationship with Vince, I doubt we’ve wasted much time talking about the equipment.”

Despite its commercial underperformance, it remains something of a fan favourite.

“It was amazing making that record,” Jones says of the project he co-produced with The Orb’s Thomas Fehlmann.

“In my mind it’s a concept album, it’s symphonic, all meant to flow together. It’s less directly pop, a bit less catchy… perhaps that’s why it did less well.

“We put a great deal of love into that record. Vince was living in London at the time and working out of his amazing, legendary round modernist studio that he’d built, and I was doing a lot of work with Andy in my little shed studio in east London, and we were trying to build the record to be this wonderful journey.

“I don’t think anyone ever said the words ‘concept album’ but in my mind that’s what it was and that’s what we made. There were some really long pieces on it. I do know it’s much loved.”

Did it hurt that it didn’t do so well commercially? Jones shrugs. “Any commercial success I’ve had has been kind of a gift from heaven, really,” he says. “I’ve never aimed at a bullseye, thinking ‘Right, I’m gonna make a hit!’ or anything like that.

“I’ve been lucky enough to have been involved with some super-talented pop songwriters and musicians and I’ve kind of been swept along by them and that’s very much the case with Vince and Andy.”

Jones worked his magic with Erasure on four further studio albums, 1997’s Cowboy, 2003’s Other People’s Songs, 2007’s Light At The End Of The World and then 2013’s Snow Globe (he also mixed the band’s 2018 album with Echo Collective, the orchestral World Beyond). Why does he think they keep coming back to each other?

“Quite often because they’ve heard something and because they know where they are with someone they’ve worked with before.

“Andy and Vince are extremely down to earth in person – really direct, no-bullshit, super-clever people, as friends and as colleagues.

“We’ve had a long relationship, so we know where we stand with each other. Sometimes that’s what you want when you’re producing a record, and sometimes it’s not.

“Sometimes you want the excitement of the new, the thrill of the unknown, sometimes you want to be in a team where everyone knows each other, and everyone knows each other’s strengths and weaknesses.”

- Read more: Erasure interview

Having worked with Erasure over such a long period, Jones is in a unique position to shed some light onto their relationship. To the outsider, Vince and Andy look like almost complete opposites, one serious and taciturn, the other playful and flamboyant, yet theirs is a professional marriage that’s lasted way longer than most.

“They’re just extremely good friends,” Jones says. “They have very different skill sets that complement each other fantastically in the sense that Vince can’t sing, and Andy hasn’t spent his life working with keyboards and synthesizers. There’s a lot of mutual admiration between them.

“I think in many ways Andy is Vince’s biggest fan and Vince is Andy’s biggest fan. As well as them being great colleagues and really good friends there’s a massive amount of support going on between them. I think they’d do anything for each other. It’s an amazing long-term creative partnership.

“In some long-term creative partnerships we all witness stress, but I’ve never really seen that between Andy and Vince. There’s not like a battle of egos going on. Which is one of the reasons they’re such a joy to work with. If there is ego, it’s left outside the studio.”

Regarding the future of his relationship with Vince and Andy, Jones says he’s just finished remixing some Erasure tracks and is currently talking with the band about “another little project” (despite much coaxing, he won’t reveal what).

Aside from that, despite being a year past pension age, he shows few signs of slowing down.

Earlier in 2020 he released his first-ever solo album, the haunting, Brian Eno-like (or, in his words, “this weird electronic record”) Electrogenetic, available via Bandcamp, while also writing new material as part of Spiritual Friendship (with Nick Hook) and Nous Alpha (with Christopher Bono). And that’s not all, it seems.

“Right now I’ve co-written and produced a record with a young woman here in Brittany, so I’m quite excited about that,” he tells us, with the infectious enthusiasm of an enthusiast with his first tape recorder.

“I’m just finishing that. Basically, I try to keep busy, and I try to keep out of trouble!”

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.