The story of Kraftwerk is not dissimilar to that of any other band; like many, it stems from pretty ordinary beginnings. There’s not an awful lot to do in Düsseldorf, and there was even less back in the late 1960s.

At this time, other key, just-beginning German acts around the country were operating independently of each other… and yet they’d all eventually come to be insultingly labelled as ‘krautrock’ as a whole.

Back in Düsseldorf, Florian Schneider (flutes, synthesisers, violin) and Ralf Hütter (organ, synthesisers) met as students at the Robert Schumann Hochschule.

Participating in the local experimental music and art scene, they formed Organisation with Basil Hammoudi (glockenspiel, conga gong, musical box, bongos, percussion, vocals), Butch Hauf (bass and something mysteriously called ‘shaky tube’), and Fred Monicks (drums and percussion), although this was not Schneider’s first foray into music, having been in the amazingly named PISSOFF in 1968.

Two become four

The transition into Kraftwerk began pretty much immediately. Heavily influenced by art duo Gilbert and George, Hütter and Schneider sought to make Kraftwerk a life and art experience.

The first two albums – Kraftwerk (released 1970) and Kraftwerk 2 (1972) – were produced by Conny Plank and were mostly experimental freeform affairs.

As Hütter explained to Uncut in 2009, “We were finding Kraftwerk, setting up the Kling Klang studio, finding musicians to work with, discovering composition, discovering the German language, human voice, synthetic voice.

“Me and Florian had our Kling Klang studio since 1970. And one day we said: ‘OK, there must be a mothership, a laboratory, a studio HQ where we put things together.’”

By the end of 1973, Wolfgang Flür had joined the pair. Flür had form already, having been in an early band with Michael Rother called The Spirit Of Sound in the late 1960s.

Another figure significant at this point was Emil Schult, who would work with Hütter and Schneider on the comic and artwork for the next album and would contribute much to Kraftwerk’s visual identity.

By the end of 1973, Hütter and Schneider had released Ralf And Florian. A move towards synths and drum machines, this was the genesis of what Kraftwerk were to become.

Kraftwerk took a giant leap forwards in 1974 with the release of their fourth album, Autobahn.

While not a fully electronic affair – there were still violins and flutes in the mix – Autobahn was a distillation of all their ideas to date, with a predominantly electronic-based sound, as well as more Vocoder, as on the title track, mimicking the “fun fun fun” of The Beach Boys.

Kraftwerk was now a quartet, with the addition of experimental musician Klaus Röder, playing treated violins (despite appearing on the sleeve of the album, Roder didn’t last long, and left before its release).

- Read more: Making Kraftwerk’s Autobahn

A radio edit of the title track, whittled down from 22 minutes to a more digestible four, saw it reach No.11 in the UK singles chart, and the album itself remains their highest charting release at No.4.

The band also made their first UK television appearance on Tomorrow’s World in September 1975, almost a year after the release of the album and five months after the success of the single in the UK.

The truth was, however, that Autobahn was something of a novelty hit in these territories.

The edit had been getting extended airplay, first in Chicago and then the rest of the US, but it was still seen as a weird bit of instrumental otherness to be filed alongside Hot Butter’s Popcorn or even Lieutenant Pigeon’s honkytonk piano theme Mouldy Old Dough.

Wave power

Any plans by Kraftwerk to capitalise on that new fame wasn’t evident with the follow-up, 1975’s Radio-Activity.

Hütter had become fascinated with the number of privately-owned radio stations in the US and was very into the idea of the band having its own private station.

Of course, the term “radioactivity” had another connotation, and in case you missed it, there were tracks entitled Geiger Counter and Uranium (in the early 1990s Kraftwerk would update the title track for The Mix album to prevent the song being seen as a hymn to nuclear power, mentioning Chernobyl, Hiroshima and Harrisburg – all sites of nuclear-based catastrophes – and prefixing the chorus with “Stop” ahead of “radio-activity”).

Radio-Activity was the first album to be performed by the ‘classic’ Kraftwerk line-up of Hütter, Schneider, Karl Bartos and Wolfgang Flür.

It was also the first Kraftwerk album to be entirely self-produced by Hütter and Schneider in their Kling Klang studio.

The independence went further: the music was published by their own Kling Klang Verlag company, giving them much greater financial control over the use of their songs. At Kling Klang, they had become fully self-sufficient in their own world.

Though at the time Radio-Activity suffered poor sales and received few encouraging reviews, it is now considered one of their key works, as David Stubbs suggests in his book Future Days; “It’s only possible retrospectively to assess the colossal size of Radio-Activity as a milestone in electronic music, one that marks a precise and signal midpoint between Stockhausen and Depeche Mode.”

European canon

Kraftwerk weren’t the masters of the dancefloor just yet. Though respected outside Germany, the group still met with some confusion, even amusement, at home.

Fortunately, someone was about to change all that – and that was David Bowie. Bowie had weaved his way skilfully through the styles and trends of the 1970s, but by 1976 he was desperate to escape a spiral of drugs and paranoia (in the States, he was in the habit of stashing his urine in a fridge to keep it out of reach of witches).

Bowie and his equally strung-out friend Iggy Pop moved to Berlin, where Bowie threw himself into German music.

Bowie’s interest in Cluster, Neu! and Kraftwerk did each side several favours: it recast him as an avatar of aheadness, and his seal of approval helped legitimised these acts, whether they wanted it or not.

There had been discussions about a potential Bowie album with Kraftwerk and he even asked them to support him on tour (perhaps these projects’ failures are a blessing, as the band might have been grafted with a permanent Bowie association).

Kraftwerk were also fond of Iggy, having long been fans of the Stooges (it perhaps seems odd that the druggy, chaotic, freeform racket of the Stooges found fans in Hütter and Schneider).

- Read more: Karl Bartos interview

Bowie, Iggy, Hütter and Schneider enjoyed a mutual friendship largely based upon shopping for white asparagus and disco dancing, and Kraftwerk name-checked the pair on the title track of their new album, Trans-Europe Express – “We’re running into Düsseldorf city/ And meet Iggy Pop and David Bowie”.

The first few minutes of the title track of Station To Station pays clear homage to Trans-Europe Express, and the ‘Berlin trilogy’ is one of Bowie’s all-time career highlights.

With rock star patronage, Trans-Europe Express marked a great leap forward for Kraftwerk, and it also sat comfortably alongside 1977’s key cultural developments.

The punks liked Bowie and, by extension, liked Kraftwerk; and then there was the onset of disco, which had been tootling along nicely for a couple of years but went stratospheric in 1977 with Donna Summer’s I Feel Love, a piece of music that still manages to sound like the future.

Together, Giorgio Moroder and Kraftwerk, in effect, laid out the blueprint for pop as we would come to know it.

Ostensibly built around a train journey, Trans-Europe Express harked back to a gentler idea of the future, and also a less dependent influence, moving towards Europe as a whole.

The album dealt with the subjects of reality and artifice; The Hall Of Mirrors reflected the experiences Kraftwerk had as pop stars with Autobahn, while the conception of Showroom Dummies stemmed from an uncomplimentary live review.

As Hütter explained, “Showroom Dummies, that is the transition from human to dummy to robots, from posing and static to animation and motorising. We were on our way to robotisation… is that a word?

“We are mainly talking about ourselves in that song, we felt photographed to death. That’s why we brought in the dummies, and later robots, because they have more patience with photographers.”

Next year’s models

1978’s The Man-Machine saw the quartet refining their sound into a less minimal, non-organic state with – whether by chance or design – a noticeably increased element of danceability. The Man-Machine was significant in inspiring the oncoming influx of chart futurists such as Gary Numan, OMD and The Human League.

The cover, produced in black, white and red, was inspired by Russian artist El Lissitzky and the Suprematism movement.

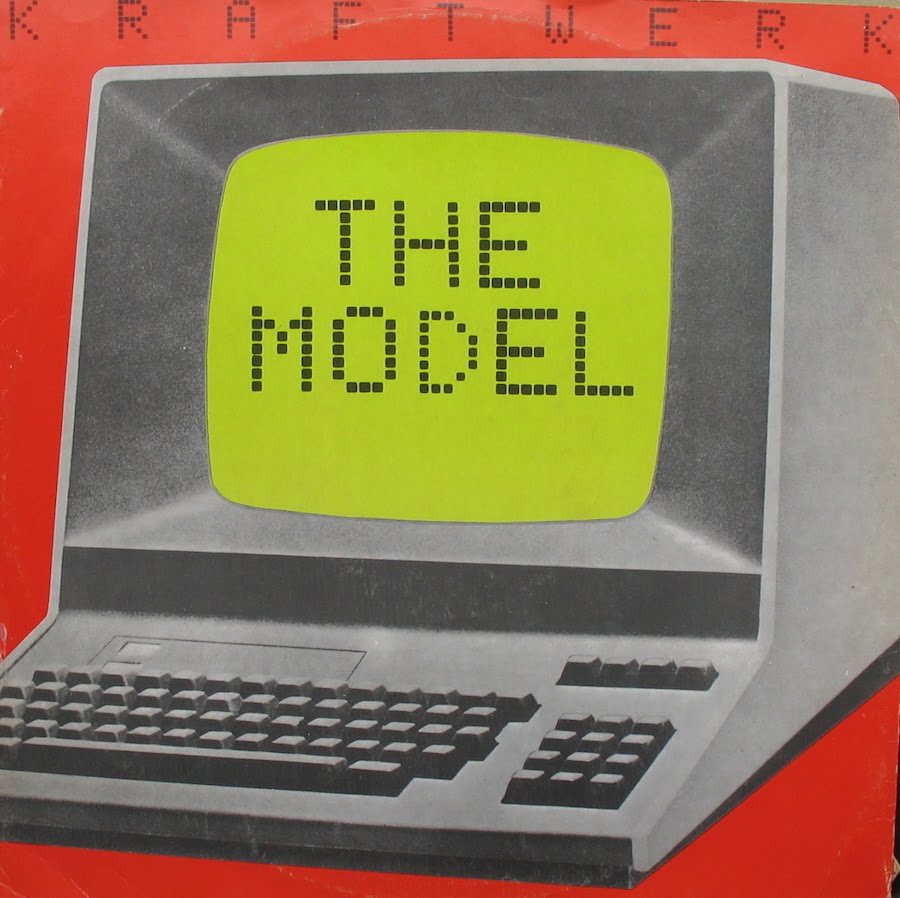

There was a slight creeping sense of democracy slipping in, with Bartos almost being co-credited for the first time on key tracks such as The Robots and The Model.

At this point there was a sense that Kraftwerk were now in an awkward position of playing catch-up after all the recent advances and developments in electronic music that had been kicked off by I Feel Love.

Still, what The Man-Machine may have lacked in foresight – despite its themes of science fiction and artificial intelligence – it made up by being the most human-sounding Kraftwerk album yet.

In some ways, the belated success of The Model redressed to a degree the imbalance of synth-pop’s big wave.

At one point in early 1982, both The Human League’s Being Boiled (which was buoyed by the nation’s new hunger for any League releases post-Dare) and Kraftwerk’s The Model would appear in the UK Top 10, with The Model topping the chart, as if to finally crown those two key records – I Feel Love and Trans-Europe Express – that had set so much in motion five years previously.

By the time Computer World arrived in 1981, Kraftwerk were back to being seen as very much of the moment.

The keenest students of the band – Soft Cell, Japan, Human League, OMD – had taken their sound and were flooding the charts with Musician Union-upsetting electronics and the strange and important sound of the synthesizer.

Computer World saw Kraftwerk take control of futurism and ideas that would soon be part of our very existence. From what once had seemed exotic and distant and enchanting, the computer had taken centre stage in human life.

Kraftwerk pre-empted online dating (Computer Love), an increasing dependence on numerals (Pocket Calculator, Numbers) and more.

Kraftwerk were seen as being pioneers of the music-making abilities of a humble calculator, playing them live mid-concert and dancing as if someone had just downloaded the moves into them, ironically, as Hütter claims: “We didn’t even have computers.

Even though the music was created by synthesisers and sequencers, it was analogue, pre-computer. We actually got our first home computers after the album was finished… the first Ataris.”

Changing gear

Behind closed doors, discontent was rife within Kraftwerk. Indeed, Wolfgang Flür’s contributions to the album were not used, though his presence on the artwork suggested he was still a band member.

1983 saw the release of the single Tour De France; originally recorded to be part of the next album, the song came out in the summer of 1983.

Featuring more complex sonic layers than Kraftwerk had before attempted, it was seen as something of a departure for the group after the two technological-heavy previous albums.

Hütter had long been a fan of cycling and had avidly followed the annual race for many years, sometimes even riding alongside it; he was also in the habit of taking a bicycle with him on tour to slip out for a bit of exercise.

Unfortunately, shortly after the single’s release Hütter suffered a cycling accident on the Rhine Dam and was unable to work with the band for some time.

The single was recorded in two versions, one English language and one German, with extra lyrics written by Maxime Schmitt, a French label associate.

Tour De France acted as an aperitif for the upcoming album, which was beginning to take up too much time to complete, partly owing to Hütter’s accident.

Electric Café finally arrived in 1986 although, befitting its troubled gestation, the album had gone through a handful of titles; the name would be changed once again in 2009 when it was reissued as Techno Pop, which had been the working title from the start.

The record was produced by French-born, New York-dwelling DJ François Kevorkian. To compound difficulties further, and probably fed up of not featuring on another album, Wolfgang Flür finally unplugged his equipment and left Kraftwerk in 1987.

Mix and remix

By the early 1990s, Kraftwerk’s work would start to play more of a part in dance music, with the group being feted by the likes of Orbital, sampled by Chemical Brothers and even touring with U2.

Soon they were firmly back in vogue, playing dance music festivals and issuing a sort-of reswizzled ‘Best Of’ with 1991’s The Mix, where, not for the first time, they rebooted and rerecorded selected ‘hits’ with varying degrees of success.

Also ahead of the 1990s, Wolfgang Flür was replaced in the live context by Kling Klang studio hand Fritz Hilpert, who had also engineered The Mix.

Karl Bartos also departed in the early part of the decade, and so – keen to keep Kraftwerk looking like a quartet – Hütter and Schneider recruited Fernando Abrantes.

At the end of the decade came another career waymark, the song Expo 2000, based around an a capella jingle and recorded for the Hannover Expo 2000 world’s fair in Germany.

A single was issued in December 1999 which expanded the jingle into a fully-fledged piece of music. Expo 2000 was later reworked to remove all Expo references and titled Planet Of Visions.

Kraftwerk’s last album of sort-of new material came in 2003 with Tour De France Soundtracks, released in honour of the bike race’s centenary celebrations.

Alongside a series of remodels of the famous title track came new tracks in the form of Vitamin, Aero Dynamik and Elektro Kardiogramm, co-written with Hilpert. The ensuing tour was celebrated with the group’s first live album, 2005’s Minimum-Maximum, compiled from shows from their 2004 tour.

During their world tour of 2008, which included a second triumphant appearance at Coachella, Schneider was absent from the line-up, with Hütter claiming he was working on other projects, and this was confirmed that November when Kraftwerk officially announced his departure from the group.

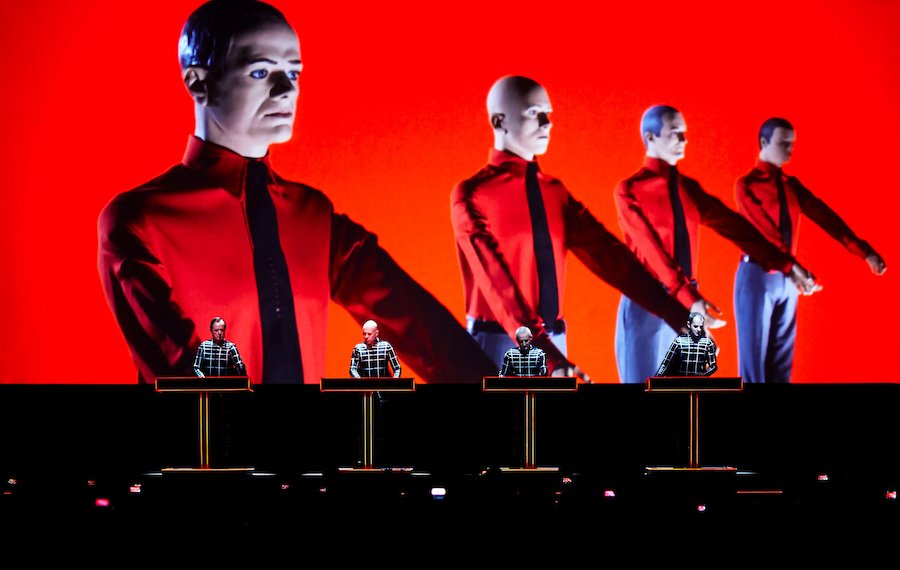

Throughout the next decade saw the touring quartet consisted of Ralf Hütter, Henning Schmitz, Fritz Hilpert and video technician Stefan Pfaffe, who became an official member in 2008.

Since then Hütter and his hired hands have continued to refine themselves into perfection.

With various tours, the reissues and an increasing level of absorption into the art world, Kraftwerk’s story is one that has transcends the band’s humdrum Düsseldorf beginnings.

It’s no overstatement to say that Kraftwerk initiated a revolutionary moment that has echoed through music ever since.

Now, more than half a century after the band was formed, it’s only right that they are saluted and celebrated as much as the other key signifiers of 21st century music.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.