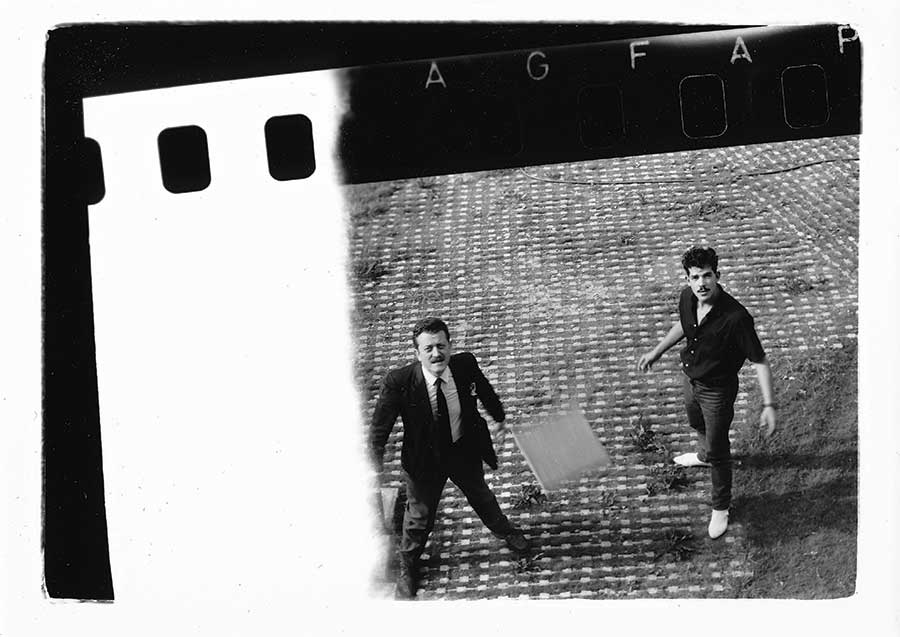

Shooting the video for Oh Yeah in 1985

After more than four decades together, “funny little Swiss boys” Yello are still innovating. In this interview from 2016, they talked to Classic Pop about stagefright, the dangers of success and the need to be “idiots” with each other…

To many, there’s something faintly comical about Yello. Their biggest hits Oh Yeah and The Race are deliberately OTT, wildly manic… and there’s always been the sense that they don’t actually need to make music.

What we know: singer Dieter Meier is from a wealthy family, and was already a millionaire industrialist when he joined the band in 1978.

Boris Blank had a more humble background, working as a truck driver before he formed Yello with his friend Carlos Peron, but he has a gift for making music for adverts and movies.

The band are known for clowning around in their videos and for Meier’s studiedly deep voice. The singer also had a reputation for his maverick art events: in 1972, six years before Yello formed, Meier installed a plaque at the train station in the German town of Kassel, stating that, on 23 March 1994 from 3-4pm, the artist would stand on top of the plaque. Sure enough, 22 years later, Meier honoured his promise.

Is Yello merely another sideline for the pair? Are songs such as The Rhythm Divine and Planet Dada just more exhibits in Meier’s conceptual art?

Talking to Classic Pop at their studio in Zurich, the pair say that they certainly try to have fun whenever they meet – but Blank’s work ethic in particular is demented by anyone’s standards, let alone for a supposedly dilettante band.

Aged 71, Meier runs a restaurant in Zurich, Ojo De Agua, which specialises in Argentine steak and wine. He greets Classic Pop by stating: “I wasn’t drunk last night, so I feel like a million bucks today.” If he’s a wine connoisseur, he also plays golf every day – “You can do that, if you make sure you find the time” – so he still looks remarkably trim.

Seven years younger, Blank, too, is in good nick, albeit with a slight ghostly pallor from constantly being in the studio. “Boris virtually lives in the studio,” Meier insists. “Our music comes about because Boris tries to find himself by creating music all day. He’s digging out the child within himself. The studio is Boris’ oxygen tent.”

“That’s true,” Blank nods. “I stick my head into music and sound so much that I could never stop now. It’s the oxygen I need to breathe.”

Dieter Meier and Boris Blank in the Pigalle Bar in Zurich’s old town, 1984

Today, Blank is happy to let Meier do most of the talking. His English, delivered in a sing-song voice contrasting with Meier’s deadpan baritone, is excellent. But he says: “Dieter’s English is so perfect and beautiful to listen to when he’s offering his perfect, beautiful philosophy.”

You also suspect Blank would rather be playing with the banks of keyboards and guitars arranged around Yello’s studio.

His love of the recording process helps to explain why it’s only now, 36 years after the release of their debut album Solid Pleasure, that Yello are playing live for the first time. In October, there will be four shows at Berlin art space Kraftwerk Studio.

Why now? “I always wanted to play live, but Boris was critical,” Meier admits. “He felt Yello could never be a truly live experience.”

Blank explains: “I thought it was always strange to be on stage shaking your ass, pretending to be live when you were simply pressing buttons on a laptop.”

Meier reveals Boris also suffered from stagefright, but explains it was cured when Blank demonstrated Yello’s interactive musical sampling app, Yello Fire, to a live audience.

“Activating the app, constructing pieces of music there and then, worked out so well for Boris that he lost his fear of being on stage.”

- Read more: Top 20 synth-pop deep cuts

Blank admits that played a part, but adds: “Also, there are many other musicians on stage with us at these shows: percussionists, singers, guitarists, trombonists, a great brass section. So it’s much more than just two guys with laptops. And that means it’s legitimate for Dieter and I to shake our asses. Dieter is one of the best dancers in Zurich.”

A full Yello tour is almost certain to follow, as Meier reveals: “If it works out and we enjoy it – and I think that will be the case – then we’ll definitely go on tour. We already have people interested in booking us. So hopefully one day, Boris and I will share a tourbus.”

Classic combination: Meier and Blank in Havana, Cuba, for the Desire video, 1986

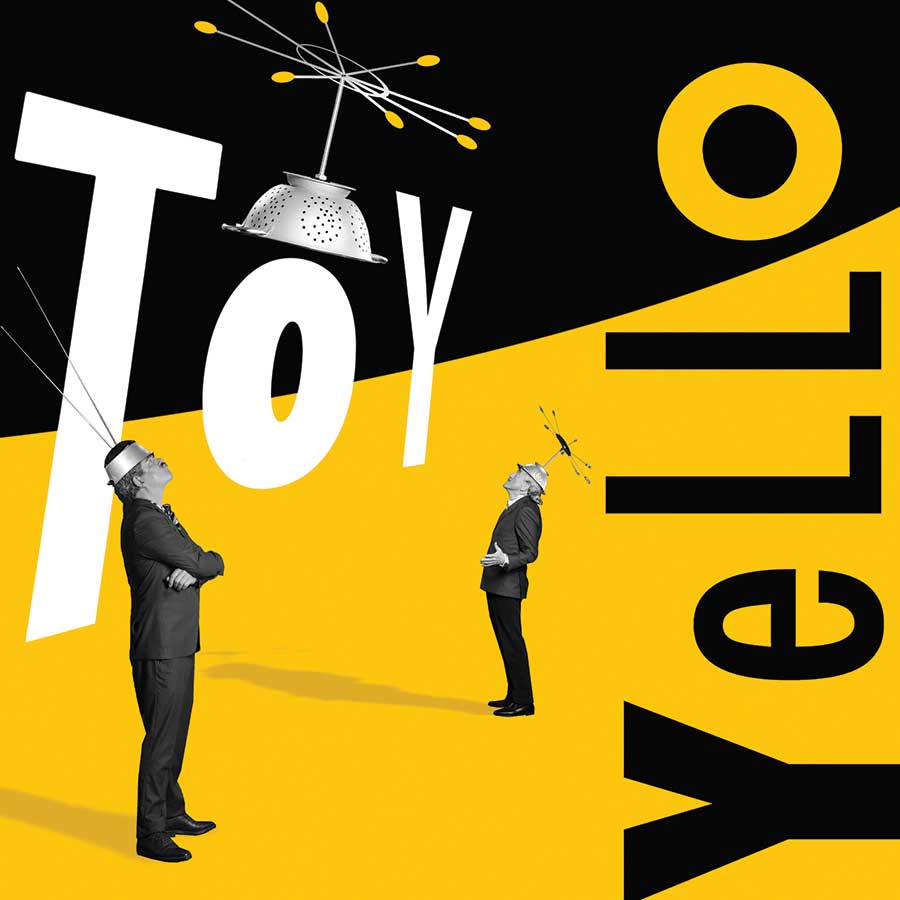

It helps that Yello are also readying one of their finest albums for many years, with the lively Toy. As exuberant as Yello’s best work, its 17 songs encapsulate their capacity for joy.

“We feel Toy is a very nice album,” says Meier, his speaking voice as rich as on his band’s music. “Our live show is big news for Yello, which in turn helps promote the album. Toy has a nice presence and is a good one for us to start our live performances for.”

Following a commercial peak in the late 80s, Yello withdrew into the background during the Nineties as Meier focused on his art. Today, the singer admits not all of Yello’s music has caught fire.

“You always believe when you’re making an album that you’re doing something new,” he considers. “But a year later, once you can reflect, you realise that you’ve disappeared up yourself. That’s not unique to Yello, it happens to every artist.

“You probably find a new door and a new room of music with your next album. But you can’t force that door open. It has to be an organic process, and those new worlds will either happen or they won’t. But we really feel we’ve opened a new door with Toy.”

The shows mean Yello’s public profile is at its highest since 1991’s Baby, which featured one of Associates singer Billy MacKenzie’s final songs, Capri Calling. Blank and Meier feel ready for more acclaim, but both are wary of being too successful.

“If you’re successful, you’re trying to feed a gorilla on your shoulders,” says Meier. “Sometimes you’re consciously feeding it, sometimes less so – but that gorilla needs feeding. If you’ve stopped having big success and you’re just a musician alone doing his thing, there’s no fear that you’re trying to make opportunistic music.”

Meier admits that, in their early days, Yello were trying to be mainstream. The only problem was, they didn’t know how. “We’re two funny little Swiss boys,” he laughs. “So when we got successful and received big advances from record companies, we felt responsible for their cash.

“We wanted to prove we were worth their money. That can be dangerous – but Boris simply didn’t know how to feed the gorilla. He never really knew how to write a hit to order.”

So the mid-80s peak when Yello seemed to be on the soundtrack to every big film of the era was by chance? “Oh, it was a total coincidence,” Meier laughs. “Before Oh Yeah, then yes, there were songs that we and our record company were convinced would be big successes.

“But our biggest hits? They were from songs we never expected to be successful. The Race? We didn’t believe in that track at all. We threw it away on a video album at first, and the video took me 10 minutes. And as for Oh Yeah? Look at the lyrics.”

At this point, Meier begins singing, and Classic Pop can confirm he can still reach Oh Yeah’s centre-of-the-earth low notes. “’The moon – beautiful/ The sun – even more beautiful. Ohhh yeah!’ Those are lyrics that are not for a wider audience, are they?”

Although Oh Yeah never actually charted as a single, it’s familiar from generations of film soundtracks, starting with Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and Tom Cruise vehicle The Colour Of Money and extending to featuring in The Simpsons, American Dad and South Park before more recently It’s Always Sunny In California. Meier appreciates its appeal.

“Everybody understands the unconditional happiness of that song. You have no more wishes in life than feeling ‘Ohhh yeah!’ The message of life’s happiness is contained in those two words, and it’s like everything has worked out for you. But we still never thought it would be a hit!”

Like other Yello albums, Toy was constructed from around 70 “sound paintings” Blank constructed from thousands of sound ideas and unreleased past Yello demos, before the musician stripped them down to 20 ideas for Meier to begin working on.

“I’m not a traditional musician,” Blank ventures. “I’m more of a mood creator, building pictures or paintings with sound. I never think in advance what mood I want to create.

“I’m like a chef who’s planted nuts in the soil, grabbing them out again and putting them together. All my sounds and fragments come together somehow, but it always feels a miracle when a coherent album begins to emerge.”

- Read more: The story of 1983 in music

If Yello broadly conform to the synth duo stereotype of flamboyant frontman and reserved studio boffin on keyboards, then initially they were rounded out with third member and fellow keyboardist Carlos Peron. A longtime friend of Blank, the pair began Yello a year before Meier joined.

Peron departed after 1983’s third album You Gotta Say Yes To Another Excess to go solo, at which point it became easier for Meier and Blank to understand each other’s work ethics.

“In the early days, the problem was that Boris wouldn’t allow me to be an idiot,” Meier laughs. “When we start an album, I have to be an idiot. I sing along like a total dilettante until a little melody or a group of words emerges.

“When I climb into Boris’ sound paintings, I’m not so much a singer as an actor, telling stories and creating scenes that further bring those paintings to life for the listener. And my stories materialise by starting from scratch.

“If I have to prove I already know what I’m doing from the beginning, then that bores me. This process has become much more open between us, and now Boris actually helps me to become an idiot, which makes it more joyful.”

- Read more: Top 20 heroes of synth-pop

For Blank’s part, although he now revels in Meier’s idiocies, he does admit that he wishes his bandmate was more focused. “Dieter has got too many things going on around his ears,” he smiles. “He does too many things at the same time and never has enough time to spend in the studio.

“He’ll be in the studio and suddenly ask me ‘What’s the time?’ ‘Oh, it’s half-nine.’ ‘Oh shit! I need to go right now!’ But, after 38 years, we still laugh a lot together. We’re serious when we make music, but there’s a lot of humour and self-deprecation. We know each other so well that we can play with those ironies.”

Toy is Yello’s first album for seven years, following Touch in 2009. During the break, Blank made the album Convergence with jazz singer Malia and released the boxset Electrified of previously-unreleased Yello outtakes and solo tracks.

Meanwhile, Meier had to write his own music for the first time when he released the surprisingly strident dancefloor album Out Of Chaos. “Yello’s songs are 90% finished when I jump into Boris’ pictures,” he admits. “I’m a guest in his world. I need to have other things in my life, so that I can get an outsider’s perspective and objective view on what to do with his wonderful paintings.

“With my record, I had to play the songs on my guitar to these nice, professional musicians. Playing shows for Out Of Chaos was fantastic. I hadn’t been on stage in the 40 years we’ve been doing this, but creating a dialogue with the audience, I’ve never felt better in my life.”

With Meier admitting “I almost got addicted” to playing live, it seems that Yello could yet become a touring band. Whatever happens, it appears likely Meier will remain happy to let his friend do the basic brushstrokes of Yello’s music.

“Oh, but I love the studio so much,” enthuses Blank. “When I’m in my coffin and the undertaker is hammering the nails in, you can be sure I’ll be lying there, trying to sample the sound so that I can make a nice little uptempo track from the noise.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.