Some kind of wonderful – the music of John Hughes

By Steve O'Brien | January 5, 2023

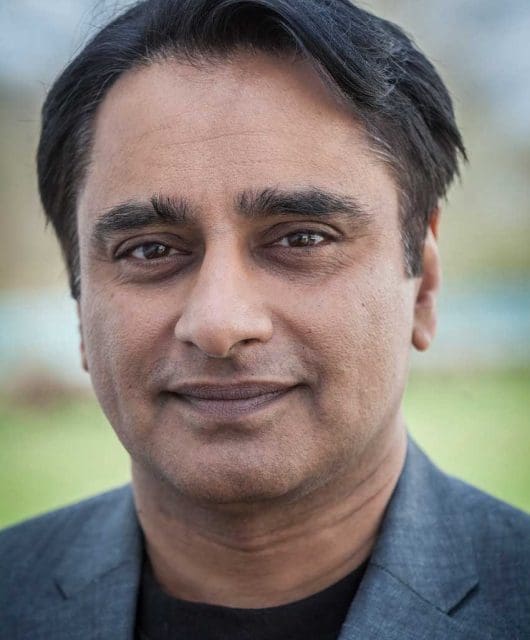

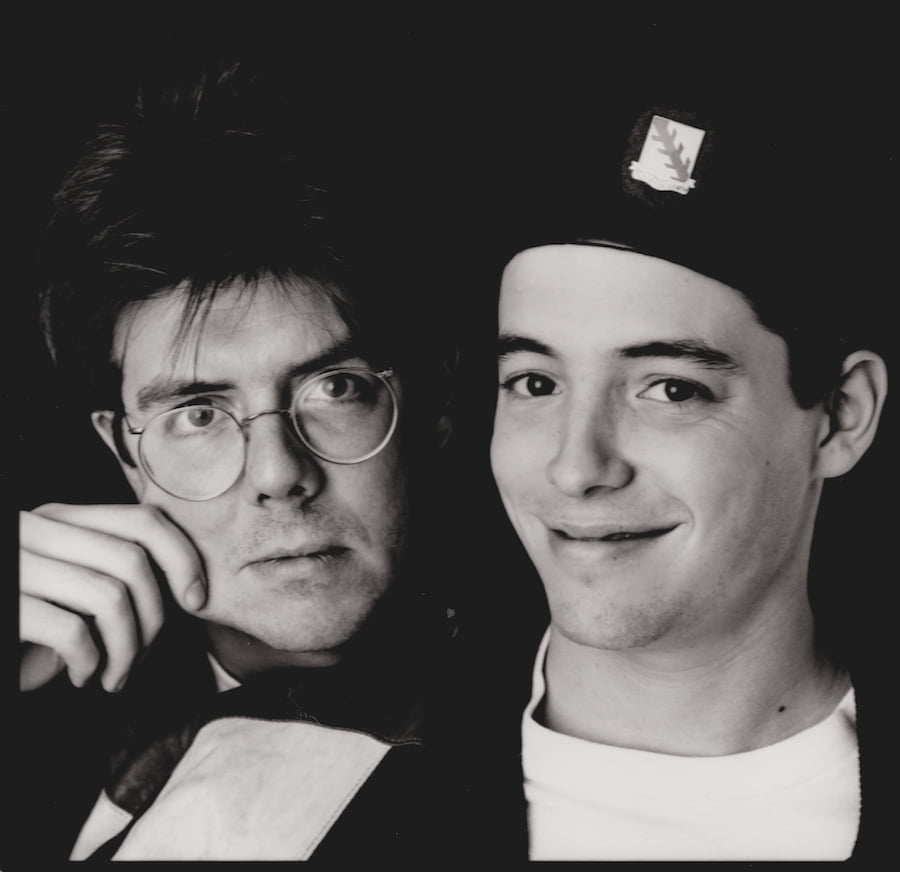

The movies of John Hughes featured some of the hippest artists of the 80s. As a boxset is released featuring tracks from many of his big screen classics, we meet the cult director’s music supervisor Tarquin Gotch and his son, John Hughes Jr

The movies of John Hughes featured some of the hippest artists of the 80s. As a boxset is released featuring tracks from many of his big screen classics, we meet the cult director’s music supervisor Tarquin Gotch and his son, John Hughes Jr

The closing moments of The Breakfast Club when Simple Minds’ Don’t You (Forget About Me) kicks in as the five high-school delinquents finish their Saturday detention.

Pretty In Pink’s Duckie sitting on his mattress, pining for Molly Ringwald’s Andie as The Smiths’ Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want plays on. Matthew Broderick miming his way through The Beatles’ Twist And Shout atop a parade float in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Indelible 80s movie moments paired with director John Hughes’ keen ear for pop.

Buy Life Moves Pretty Fast: The John Hughes Mixtapes (Deluxe Edition) on Amazon

If you were a teenager in the 80s, it’s almost inevitable that your life bumped up against a John Hughes movie at least once. Back then, while plenty of directors were making films for teenagers, barely anyone was making them about them.

Which is why those movies are recalled with such affection. The Breakfast Club, Some Kind Of Wonderful, Pretty In Pink, Sixteen Candles, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Weird Science, She’s Having A Baby… Classics one and all.

Music was always a vital part of Hughes’ features. He virtually invented the needle-drop soundtrack, so much so that Quentin Tarantino, Danny Boyle and Edgar Wright all owe him a huge debt. His soundtracks, however, were never about chasing the fashions of the time.

As great as the original Top Gun is, its OST hasn’t aged well. Look, though, at the tracklisting for the same year’s Pretty In Pink – The Psychedelic Furs, OMD, Echo & The Bunnymen, Suzanne Vega, The Smiths, Nik Kershaw – even now, that soundtrack rocks.

The difference was, John Hughes was as crazy about music as he was film and knew instinctively what song to marry to a particular scene.

“He would write to music,” Hughes’ music supervisor Tarquin Gotch tells Classic Pop. “He’d have it playing the whole time. I mean, even a lot of his film titles come from songs, so there’s a huge clue there how much music meant to him.”

Let’s rewind to 1985 and Gotch, who by that time had been an A&R man at Arista and WEA and was by now in music management, looking after The Beat, Stephen Duffy and XTC. Staying with his friend Kelly LeBrock in Beverly Hills, the actress invited Gotch over to Universal Studios while working on Weird Science.

Tarquin got talking to its director and, as he recounts: “John quickly realised an ex-A&R man and manager from London would have access to all sorts of British music that no one in L.A. could get, simply by the fact I knew it existed.”

While in production on Weird Science, Hughes was also busy prepping his next film project, Pretty In Pink, which Gotch was invited to become music supervisor on.

The Brit quickly became used to long phone conversations – often in the middle of the night – where Hughes would talk him through every scene of whatever movie he was he was working on, describing what he wanted the music to do. Gotch, in turn, would send Hughes piles of cassettes with possible songs to choose from.

“He would sometimes put the music in the script, but the reality of filmmaking, particularly before John became mega-successful, was that you can’t always get what you want,” Gotch says. “The Beatles in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off was the most hair-raising for me.

“They shot the whole thing before we got a yes from The Beatles, so you’re between this rock and a hard place. You can’t take the scene out, it’s got The Beatles, so you have to get it.” (Lead actor Matthew Broderick later recounted bumping into Paul McCartney, who told him, “You did well with my song.”)

The Fabs, however, weren’t a typical band to crop up in a Hughes movie. Despite his age (35 when he made Ferris Bueller…), Hughes was no nostalgist and had as much curiosity for contemporary music as that of his past.

“He always stayed young but with the recognition that he wasn’t young anymore,” Hughes’ son, also called John, tells us. “As he got busier and older, he just found young people to have around him that helped him stay on the pulse of what was happening in music. They’d make mixtapes for him, so he could continually keep current.”

This inquisitive nature meant that, Hughes didn’t automatically reach for the biggest hit of the day or some jukebox favourite from his youth for the soundtracks.

As well as being a devoted Anglophile (as a teenager he was an avid reader of NME and Melody Maker), he was always interested in up-and-coming bands and artists.

“I think part of why he went after smaller bands is when he was growing up he was moved around a lot,” says Gotch. “He didn’t have lifelong friends at school, so I think one of the ways he bonded with new friends was in his choice of music.

Being into hip imports gave you a certain cachet and attracted a certain sort of friendship group. So right from being a teenager, he was prone to go after those import bands, groups on the edge of success rather than the Led Zeppelins, Beatles and Pink Floyds.”

It’s those artists who are (mostly) celebrated on Life Moves Too Fast: The John Hughes Mixtapes, a 4CD/6LP boxset, compiled by Gotch, which collects together more than 70 tracks from 11 of the great man’s movies, including non-teen films, such as National Lampoon’s Vacation, The Great Outdoors and Uncle Buck.

Though it’s well packed, there were songs that Gotch had chased that he couldn’t secure the rights to. He regrets not being able to convince the Stray Cats to let him use Sixteen Candles, that featured in the film of the same name.

“I mean, I signed them and even knowing the band and being able to phone them up and say, ‘What the fuck…!?’ His voice trails off with exasperation.

Gotch has been working on this project for three years, alongside Hughes’ son, who looks after his father’s estate (Hughes Sr died in 2009). “I’ve been wanting to do this for a long time,” he says. “It’s been a labour of love.”

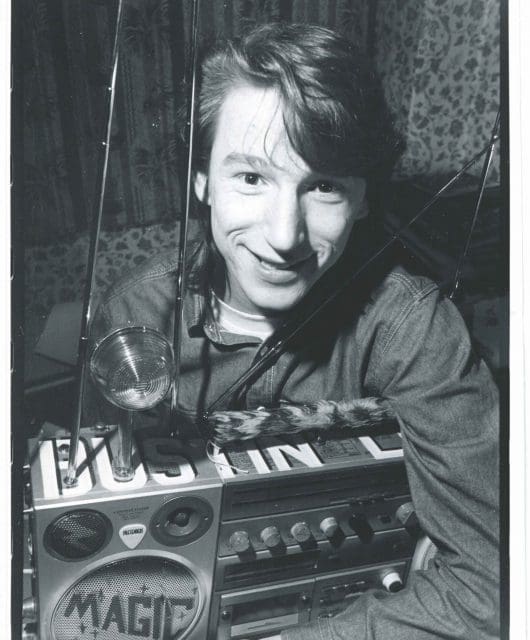

“I think Tarquin viewed it as a sort of legacy project,” John Hughes Jr tells us over Zoom from the US. “For him, it was obviously really meaningful, working on those films, helping arrange all the music for my dad. For me, it was a really natural idea, because it was something my father talked about before he passed away.

“I didn’t have to give it much thought knowing that Tarquin was involved as he was someone dad had trusted with his music in the past. It seemed like a good thing to do to honour him.”

Hughes and Gotch enjoyed a close working relationship that culminated in Tarquin moving to Chicago in the early 90s to run the director’s film production company/music label, Hughes Entertainment.

That Gotch was involved in the music and British helped their professional bond, but it was also that they shared much of the same taste culturally. Tarquin became Hughes’ go-to man for keeping his finger on the British pop pulse.

“In a world pre-streaming, being able to find any piece of music you want at the click of a button, being able to get your hands on demos or 12” mixes, or an instrumental mix, was a big deal,” says Gotch.

“So knowing that I could do all that for him made me valuable. Of course, it was the chance of a lifetime to work with an A-list film director, who I always thought was the Frank Capra of his time.”

“He used music and film in a very different way and people are still using music that way now,” ponders Hughes’ son. “At the time he had to fight about how loud he wanted the music up in the mix, because generally you didn’t put the music up that loud.

“The sound guys were saying, ‘I think it’s stepping on the dialogue a little bit’ and dad would say, ‘I don’t care, the emotion of the music is really feeling that scene and helping it.’ He changed the way music was put against pictures.”

Asked about his favourite musical moment, Gotch finds it hard to pick just one. He cites the Don’t You (Forget About Me) sequence from The Breakfast Club as well as the Twist And Shout section of Ferris Bueller… but it’s The Dream Academy’s Power To Believe in Planes, Trains And Automobiles, played as Steve Martin is recalling the fun times with John Candy’s character, that gives him the most joy.

“John shot Steve thinking in all sorts of different ways,” he says. “He needed to show that Steve had worked out that Dale [John Candy] had nowhere to go, no home to go to – The Dream Academy there was just perfect.”

Hughes’ name is synonymous with the 80s because he’d pretty much retired from film by the start of the 90s. Although he penned the screenplays to the various Home Alone sequels, he didn’t direct another movie after 1991’s Curly Sue. A giant loss to cinema.

“He was just tired,” Hughes Jr tells us. “He gave up so much of his personal life for making films that he just wanted to take a break. But he continued to sketch ideas and even write scripts, but I don’t think he wanted to get into a full-on production.”

Although his interest in moviemaking had waned, the 90s and noughties seemed to allow more time for Hughes to indulge his passion for music.

His son tells us that in his later years he’d be ‘hyper-focused’ on one particular genre and become obsessed in tracing it back to its roots. “He absolutely kept his obsessions about music,” he says. “He really wanted to understand the lineage of it, the history of it, taking it back as far as he could.”

Now 13 and bit years on from Hughes’ death, this new boxset is a fitting testament to a filmmaker who married music with the moving image better and more emotively than any director before him. And it’s a precious time capsule of an era in movies when, for a short time, the teen was king.

“If anybody wanted to know,” Gotch continues, “what it was like if you were a middle-class suburban kid in the 80s, before the internet and mobile phones, you only have to sit down and have the pleasure of watching John’s teen movies…” He pauses. “And hearing their great soundtracks!”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Steve O'Brien

Steve O’Brien is a writer who specialises in music, film and TV. He has written for magazines and websites such as SFX, The Guardian, Radio Times, Esquire, The New Statesman, Digital Spy, Empire, Yours Retro, The New Statesman and MusicRadar. He’s written books about Doctor Who and Buffy The Vampire Slayer and has even featured on a BBC4 documentary about Bergerac. Apart from his work on Classic Pop, he also edits CP’s sister magazine, Vintage Rock Presents.www.steveobrienwriter.com