Ultravox Quartet

As Ultravox’s Quartet album gets the deluxe reissue treatment, Midge Ure and Billy Currie recall the highs and lows of its creation with legendary producer George Martin

How’s this for a musical time capsule? It’s the summer of 1982, and in Air Studios, high above Oxford Circus, Ultravox – who are recording their latest album with producer George Martin – are invited into the next-door studio to witness a product demonstration of an exciting new music format called the compact disc.

“I think McCartney was in there as well,” recalls Midge Ure, four decades on. “I can’t remember if it was Phillips or Sony, but they played this thing and we all went, ‘Wow, that sounds amazing’…”

And if that’s not pure, distilled 1982 enough for you, mere weeks after Duran Duran had sailed around Antigua in pastel Antony Price suits shooting the video for Rio, Ultravox decamped to mix their new record on the Caribbean island of Montserrat.

“It was spookily beautiful,” says Billy Currie, the band’s multi-instrumentalist keyboard wizard. “I remember, just after we’d arrived, turning a corner and finding the entire road covered in about two feet of mangoes.

“I went a bit further, and came across some people who were living in a tree – actually living up there. It was pretty far out.”

In the 80s, of course, such lavish excess was par for the course for any band who were filling their label’s coffers.

And in 1982, Ultravox were at the top of their game: after failing to catch fire commercially with original frontman John Foxx, their fourth album, Vienna – the first with Ure as vocalist – had become a huge hit on the back of its iconic title track, with follow-up Rage In Eden also doing great business.

But when the four-piece – Currie, Ure, drummer Warren Cann and bassist Chris Cross – convened to record what would become Quartet, certain eyes at their label were already moving on to the next prize: America.

“I’m not sure if it was ever said at the time,” says Midge. “But I tend to think this was the album they thought might catch the American market.”

So who better to take the reins than the man who’d helped mastermind the ultimate British Invasion. At the time, though, dropping the band’s long-serving producer – krautrock and kosmische pioneer Conny Plank – in favour of George Martin was a controversial move among some Ultravox fans, who saw The Beatles’ studio guru as an overly safe, conservative pick.

“As a student, I’d spent many an hour flat on my back listening to Sgt Pepper, so he was a bit of a hero,” continues Billy. “But I was aware of the criticism and probably a bit affected by it myself, if I’m honest.”

- Read more: Ultravox – album by album

“He was old-school, compared to Conny,” reflects Ure. “Conny was this kind of mad, German hippie – and there’s George, in his shirt and tie. I think we did all have some doubts about ‘Will he have kept up with the technology?’

“But of course we get there and he’s bought himself a LinnDrum, he’s worked out the timings to put a delay on the snare…”

In fact, despite Martin bringing in engineer Geoff Emerick for the full Beatles experience, the band ended up being slightly disappointed by the lack of cut-and-paste studio experimentation.

“I think we were all probably hoping for a bit more throwing tapes in the air and glueing them together, backwards vocals, that sort of thing,” admits Midge.

“But that stuff has to come from the band. It’s not really for the producer to say, ‘Here’s my trick number three, we’ll put you through a Leslie cabinet’, or whatever. They don’t work that way.”

Either way, he was impressed by what he called “the most musical group” he’d come across in a while – which is probably a credit, in part at least, to Currie’s classical chops (a decade or so earlier, Billy had turned down a place at the Royal Academy of Music to join the rock and roll circus).

“He knew I could match him when it came to notation, scoring and stuff,” says Currie. “I think George thought, ‘We’ve got a proper musician here, a thinker’. So I enjoyed working with him, and talking things through with him.”

“George was such a pleasure to work with,” adds Ure. “He was like everything you’ve ever seen on the documentaries.

“He couldn’t get too ruffled about any harrumphing or infighting in the band. I’m sure he’d seen many an issue with The Beatles – we were rank amateurs in comparison! Walking into Air, you’d hear a bell ringing behind you and it would be George on his bicycle, with his hat on.

“He’d say, ‘Good morning, chaps’ and cycle right into the elevator, then turn around and cycle out of the other end. He was just a brilliant, wonderful eccentric Brit.”

Martin – who, according to Billy, “stuck to office hours” – was juggling Quartet production duties with Paul McCartney’s Pipes Of Peace album, and the former Beatle was one of many famous faces who dropped into the studio.

“McCartney telling us, ‘I like that Vienna, is a great memory,” smiles Currie. “But there were all sorts of people – Kate Bush came in, Pete Townshend… I remember Prince Charles coming in at one point to see George!”

So were the fans’ fears about this friend of pop royalty – and actual royalty – justified?

“I don’t know if we were playing it safe,” muses Midge. “But it was certainly a massive departure from Rage In Eden. That was a very dark, spiky, ominous record, whereas Quartet was much more polished and shiny. It was a very grown-up sounding record – maybe a little too grown-up.

“I think too many of the rough edges had been taken off, and that was probably partly to do with George. But I’m not complaining. You don’t go and buy a Rolls-Royce and then feel miserable because you’re driving a Rolls-Royce…”

“There’s a slight establishment safeness about it,” agrees Billy. “It’s much less intense than the previous two albums. I wouldn’t say it’s MOR, but we’re not creating anything particularly new – it’s a record from an established band, showing off what we’ve got.”

- Read more: Ultravox – The complete guide

Anthemic opener Reap The Wild Wind was selected as Quartet’s first single, landing just outside the UK Top 10 in September 1982. “That pissed me off a little,” admits Currie.

“It was originated by Midge at home, so it wasn’t a full collaboration, and we ended up banking on something which I thought wasn’t quite there.”

Follow-up Hymn fared better across Europe, and is arguably Quartet’s signature song. Nevertheless, it was Reap The Wild Wind that Ultravox chose to open their Live Aid set with three years later.

“We knew it was a banger,” insists Ure. “But we’d also worked out it was one of the songs we could play with the least equipment, because there was no soundcheck.”

“When we finally got together again to work on the next record [1986’s U-Vox, by which time Ure had also scored a hit solo album, The Gift, and a No.1 single, If I Was], it was all over,” says the singer. “Psychologically, we’d just lost it.”

And America? History records that Quartet – Ultravox’s third UK Top 10 album on the bounce – was indeed the group’s highest-charting long-player Stateside… but it still peaked at a lowly No.61.

“It was disappointing, because we’d got it into our heads that we wanted to crack America, and really, that was our chance,” says Billy. “But we were still as difficult as hell. We never did anything straightforward.”

“We were our own worst enemies,” agrees Midge. “With this album, we got up to 3,000-capacity theatres. But then we couldn’t go any further because the next step was to open up for somebody else, which you can’t do when your soundchecks last five hours and you refuse to use backing tapes. So it stalled, and then flatlined out there.

“What irked more than anything was that everyone who was behind us in the queue overtook us and became huge in America,” Ure adds, with a rueful laugh. “We were used as a battering ram.”

So while the likes of Simple Minds and Depeche Mode enjoyed stadium-filling success in the States, Ultravox went their separate ways after the U-Vox tour.

In the 90s, Billy put out a couple of albums under the Ultravox banner, but it would be more than 20 years until the classic line-up reformed for five years of shows and a new album, 2012’s Brilliant.

And that, we assume, is that… Isn’t it? “Well, we’ve said ‘never again’ before” notes Midge. “The reality is we’re a weird bunch. You know, we’re men – we don’t pick up the phone to each other. I see Chris now and again, I get the odd email from Warren.

“The last thing we did was opening for Simple Minds on their arena tour [in 2013]. Afterwards, we dropped Billy off at the station, gave him a big hug, said ‘Happy Christmas, I’ll speak to you later’ And that was 10 years ago…”

Currie is less ambiguous. “It’s a definitive full stop,” he says. “It was a different thing for me, because I was the one person who didn’t leave. Which kind of sums up my personality. I mean, it’s just not the done thing, for the instrumentalist to carry on the band, and I came up against a complete brick wall.

“It was very difficult. When we got back together, it was great – I really did enjoy it. But at some point you’ve got to draw a line under it, and to come out and say so.”

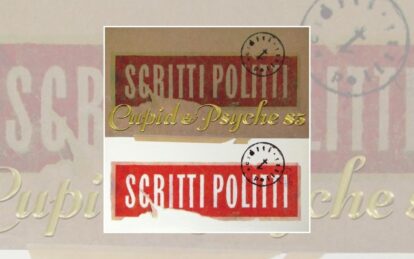

The band’s legacy is kept alive, though, not least through Chrysalis’ lovingly curated series of deluxe reissues of the Ultravox catalogue – of which the recent lavish 70-track, 6CD+DVD Quartet boxset – also available in various vinyl configurations – is the latest. “It feels good,” admits Billy. “It feels like you’re being really respected and appreciated.”

Among the highlights of a deluxe set boasting no fewer than 47 previously unreleased tracks is a new stereo mix of the album by studio alchemist Steven Wilson.

Ultravox Quartet

“The way he’s able to clarify, and clean, and create space between every note, is incredible,” marvels Ure. “It’s black magic. And I also love the fact people still respect and admire not just the music, but the artwork and the packaging. They’re real objects of desire, these boxsets.”

Could any of them have imagined back in 1982 when the compact disc was still a shiny new technological miracle, that such an object might one day exist? Midge shakes his head.

“Back then, a record came out and it had maybe a six-month lifespan, then it was gone,” he says. “It was never seen as anything with any real longevity.”

Most pop stars, it was assumed, would enjoy similarly mayfly careers. And yet here they are, more than 40 years on, still performing still composing, still playing in the musical sandbox, with a lifetime of memories: of working with George Martin, playing at Live Aid, and shooting the breeze with Paul McCartney, five floors above Oxford Circus…

“Whenever I’m in Glasgow, and have a few hours to spare, I go back to where I was born,” says Midge. “I walk up and down the same streets I walked when I was kid, wishing for all this.

“Because it’s so easy to take it all for granted. I have to remind myself: ‘I got my wish’. And here I am, coming up for 70, still doing it.”

At which point, presumably, all the setbacks and disappointments along the way get lost in the sweep of history? “Yeah, yeah,” nods Ure. “Even the bad bits were good. Now, even the arguments seem fun.”

All photos by Brian Aris

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.