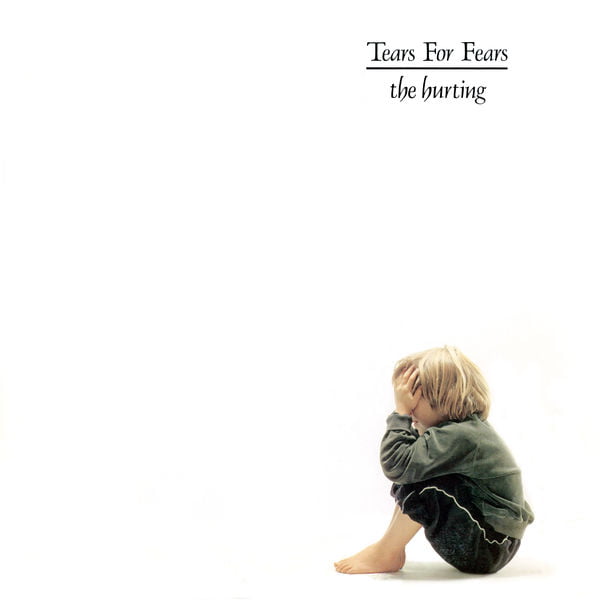

Making Tears For Fears: The Hurting

By Classic Pop | August 19, 2021

In 1983 Tears For Fears’ The Hurting introduced the world to a band that blended bleak musings on the long-term effects of childhood trauma with a razor-sharp synth-pop instinct. The result: an instant classic… By Wyndham Wallace

When Roland Orzabal was growing up – first in Portsmouth and later in Bath – his parents ran an entertainment agency for working men’s clubs. Among the guests auditioning at his home were singers, ventriloquists and strippers; even his mother was a stripper.

It was, you might say, inevitable that he’d end up on stage himself. But if this sounds like a boisterous childhood, behind the curtains things were less happy. Orzabal’s parents were at loggerheads: his father, a WW2 veteran, was far from healthy and given to fits of fury that drove his wife away after bursts of domestic violence.

But Roland was about to meet his future musical partner Curt Smith, who was also enduring a troubled childhood, growing up on a local council estate in a broken home where money was a significant problem.

“He was a lot more rebellious than I was,” Orzabal recalls, “which shocked me because I was a good boy at school and quite conservative as a character. We were out once in Bath, and a police car pulled up and said, ‘Come with me.’ Curt stole a couple of violins from the school for my birthday present. Not that I played the violin!”

Thankfully, Orzabal’s musical partnership with Smith would flourish in other ways and lead to the monumental 1983 album The Hurting.

That album – and, to a degree, 1985’s multi-million-selling follow-up, Songs From The Big Chair – were, as Smith puts it, therapeutic attempts to “find out why our backgrounds were so messed up”.

Tears For Fears: The Hurting – Mutual therapy

Orzabal found Smith’s recklessness as appealing as Smith found Orzabal’s intellect, but the two really gelled after Orzabal’s guitar teacher pressed a copy of The Primal Scream, by US psychotherapist Arthur Janov, into his hands. Orzabal was already buried in existentialist books by the likes of Sartre and Beckett, and this new addition to his library became his bible.

“Aged 17 or 18, I was an absolute convert to Janovian ‘primal theory’,” Orzabal says, though Smith adds that, “The fact that you’re screwed up because of your parents is hardly brain surgery. We were both slightly evangelical about it.”

Tears For Fears: The Hurting – Mad World

Nowadays, Orzabal jokes that his pious proselytism turned him into “a primal bore”. But, as the two of them sought to make sense of their psyches, Janov’s tactics – to revisit childhood trauma – provided a framework for their lives to such an extent that it would eventually give them a name for their band.

Tears For Fears, however, was not their first musical endeavour together. They’d already experimented with friends, playing everything from folk to rock, and signed their first deal at 18 with a moddish band called Graduate, known in Spain for their radio hit Elvis Should Play Ska.

The band recorded one album, but the experience was most notable, Smith argues, for teaching them “what not to do: we learned that we weren’t made for travelling in two mini-vans. I don’t think we were comfortable in the live setting. And we don’t like being in five-person democracies where we constantly get outvoted by the others, even though we’re the only two that write songs.”

Inspired in part by Gary Numan, whose use of technology proved that you didn’t need a band to make music, they split from Graduate and set about recording as a duo.

Hooking up with local producer David Lord – who’d already co-produced The Korgis’ Everybody’s Got To Learn Sometime, and who’d soon helm Peter Gabriel’s fourth album – they demoed their first songs, including Suffer The Children, at Bath’s Crescent Studios.

A meeting at a “vegetarian disco” (in fact, the city’s enduring Moles club) with Ian Stanley – a “rich kid”, Smith says, who had his own studio and would go on to join the band on keyboards – allowed them to experiment with their sound.

Their publishing company from their Graduate days, run by Tony Hatch, composer of the Crossroads theme, helped get them signed. Only two showed interest: A&M, and Polygram’s David Bates, who recalls how he nearly let the band slip through his fingers after being played songs by the publisher’s representative, Les Burgess.

“Les’ job was to visit A&R managers and play them songs in the hope that one would be picked and used for a recording session,” says Bates. “As usual, I had no artists looking for songs. After he’d gone, I thought about one of the cassettes I’d heard. I ran after him, stopped the lift, asked for the cassette and told him I wanted to listen to it a couple of times over the week. After another play, I was sure the songwriters would be an interesting act.”

To the duo, the only surprise was that it took so long to get a deal. “We were sure of ourselves,” Smith smiles. “I remember arguing with A&R people that turned us down. I’d say, ‘Well, you’ll be sorry one day…’”

Tears For Fears: The Hurting – Change

But their confidence required stamina. The deal with Polygram was only for two singles, and neither 1981’s Suffer The Children nor 1982’s Pale Shelter (produced by ex-Gong member Mike Howlett) charted.

“Normally, you’re either a critically acclaimed band that are pretty deep,” Smith elaborates of the difficulties they faced making commercial headway, “or you’re a pop band, and never the twain shall meet. But we achieved that. We had the screaming girls, which is the pop side, and we had people analysing our lyrics. College kids who were deeper thinkers appreciated us. So it was a weird mixture and people didn’t quite understand.”

Tears For Fears: The Hurting – Worlds ahead

After further recordings with Mike Howlett left the band dissatisfied, they turned to Chris Hughes. “We didn’t know he was Merrick in Adam And The Ants,” Orzabal laughs. “We knew him from a band called Dalek I Love You. We just saw him as a record producer.”

As it happened, Orzabal had already spoken with Hughes in early 1982 after the producer had wandered past Bates’ London office during a visit that coincided with the duo’s embryonic sessions with Howlett.

“David shouts, ‘Come have a word with this guy on the phone,’” Hughes remembers. “I spoke to a quietly-spoken gentleman who was concerned about some recordings he’d made. I listened, tried to allay his fears and handed back the phone. Some time later, when discussions about producers were being held, the highly articulate Roland Orzabal said, ‘What about that guy I spoke to on the phone? I’d like to meet him.’”

To begin with, it turned out to be a felicitous collaboration, with Hughes working alongside engineer Ross Cullum, and its first real fruits were unexpected, as Bates reveals: “Chris called me one night and asked me to come by the studio and listen to a B-side they’d been working on. I was enthralled. This was no B-side. I wanted this out as soon as possible as an A-side. If this gave me a hit – small, low-end charts – it would give us time to complete the album without pressure.”

Tears For Fears: The Hurting – Pale Shelter

The song was Mad World and, as Bates continues, “It was like nothing out there: a little slow, maybe, but what a chorus! The sound was unique. I believed this was a hit. The hit we needed – the hit I needed.”

The band recognised they were onto something. “I remember Roland dancing around the studio,” Hughes recalls, “which would crop up as and when he got over-excited.”

It wasn’t only in the studio: the video also featured Orzabal’s unique moves and helped propel the record slowly up the UK charts, where it peaked at No.3 and gave the group their first crucial TOTP appearance.

Read more: Top 40 80s debut albums

Read more: Adam Ant interview

But this had repercussions: now they found themselves interrupted by publicity duties, and the pressure of success weighed heavily on them. “The bar had been set quite high,” Hughes confirms, “both by the band internally and by record-company expectation. The culture developed, wrongly or rightly, that the longer it took, the more excellent it was.”

Additionally – according to Bates – Orzabal, Smith, Hughes and Cullum were all perfectionists. “A lot of the time, it was myself and Roland wanting it one way,” Smith remembers, “and Ross and Chris wanting it another way. So there was a two-against-two battle throughout the album.”

“The combination of that quartet led to a ridiculous amount of procrastination,” Orzabal confides. “There was a hell of a lot of pressure to get the thing done, so we’d be working seven days a week, until two o’clock in the morning. There was too much talk and too much theory. We couldn’t get anything onto tape if all four us didn’t agree. That’s the problem with democracy, isn’t it?”

Tears For Fears: The Hurting – The Hurting

In the end, it all proved worthwhile. Inspired by the likes of Bowie’s Scary Monsters, Talking Heads’ Remain In Light and Peter Gabriel’s third album (known as Melt), as well as by Janov’s primal-therapy theories, The Hurting was a pensive yet poppy concept album about childhood, which blended the duo’s explorations of their interior worlds.

“We were your archetypal shoegazers,” Orzabal claims – with a melodic sensibility. Its melancholic tone couldve kept them away from the mainstream, but somehow its universal themes of alienation and teenage confusion connected with a mass audience. “The reason it still has such appeal is that those are the feelings that surface,” Orzabal states. “A lot of people go through that phase. We were happy to take on semi-intellectual concepts and try to turn them into hits.”

The accessible nature of Pale Shelter and the fourth single, Change, meant their audience were prepared to indulge them in more challenging songs such as Ideas As Opiates and The Prisoner. This enabled The Hurting to knock Michael Jackson’s Thriller off the UK top spot and remain in the UK charts for 65 weeks, achieving platinum status.

The record even reached the ears of the man that had inspired it, Arthur Janov, though the duo admit that their meeting didn’t go well. “He was aware that we’d written the album based on primal theory,” Smith relates. “He came to a show and we felt like it was playing in front of God. He came backstage and he was incredibly nice, inviting us for lunch.”

“We were extremely nervous,” Orzabal adds. “It was the equivalent of somebody in Scientology meeting Ron Hubbard. Then we found out he’d written a musical. Yeah. Exactly. I just walked away thinking, ‘Hmm. Never meet your heroes!’ The words to the musical were just… worse than my own lyrics, actually!” “It seemed wrong,” Smith summarises, “because we held him in such high regard that it seemed to commercialise the whole thing. It’s like God turning up in a race-car driver’s jacket with sponsors.”

Tears For Fears: The Hurting – Pale Shelter

The Hurting stands as one of the great debut albums of the 1980s, beloved by artists as diverse as John Grant, Billy Corgan, Kanye West, MGMT, Swiss Beatz and Gwen Stefani. “Our audience goes from 16-year-old kids to 50-year-old parents,” Smith states happily. “I think The Hurting is geared – not intentionally, but because we were that age – towards adolescence. It talks about those dark years of 18 to 23 when you’re trying to find yourself. That, I think, is because it has a depth of emotion and meaning.”

“It is,” Orzabal concludes, “the one true Tears For Fears record. The band’s name, the whole ethos: everything we believed in was summed up in that record.”

Read our feature on the making of Tears For Fears’ Songs From The Big Chair

Read more: Roland Orzabal interview

The Hurting – The Songs

The Hurting

The Hurting was inspired musically by Curt Smith’s recollections of a show by Bristol band Electric Guitars. “Curt described their music,” Orzabal recalls, “and I wrote the guitar riff.” The song was later sampled for Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas? “I found that amusing,” Smith laughs, “‘cos they didn’t invite us!”

Mad World

The first track recorded for the album, this breakthrough hit was inspired by the view from Orzabal’s Bath flat and originally slated as a B-side for Pale Shelter, until producer Chris Hughes and A&R David Bates recognised its considerable potential. “It’s a static melody,” Orzabal admits. “Curt’s voice made the song legitimate, or else it would’ve gone in the dumper.”

Pale Shelter

First demoed at keyboard player Ian Stanley’s studio, the band’s second single earned them, according to Bates, “little nibbles but no bite”. Among these was a John Peel session, broadcast in September 1982 (and included as part of the album’s 30th Anniversary Edition). A love song about parents rather than partners, Pale Shelter was, Orzabal says, one of the album’s more difficult compositions. “I had the verse for a long time but no chorus. My wife had this book on painting, and there was a Henry Moore work in there called ‘Pale Shelter’, about homeless people. I thought, ‘That’s good,’ so then I came up with a chorus and the song was complete.” Pale Shelter was later re-recorded by Smith for his Aeroplane EP, released in 2000.

Ideas As Opiates

The song that supplied the B-side to Mad World was also one of the album’s most challenging tracks and was named after a chapter in Arthur Janov’s Prisoners Of Pain, published in 1980, 10 years after his seminal The Primal Scream. “Now, who the hell would write a song called that?” Orzabal laughs, before recalling how it baffled John Peel’s engineers. “It contains different chords – a major third and a minor third together – so we played them and the engineer stopped the tape. ‘You’ve made a mistake!’ he said. ‘No,’ I said, ‘that’s how it goes.’”

Memories Fade

Featuring the key Janovian philosophy, “Memories fade but the scars still linger,” this track was liberally ‘sampled’, with largely new lyrics, by Kanye West for Coldest Winter on 808s & Heartbreak. “I was surprised because he didn’t really ask,” says Orzabal. “But when we do it live, we now use the Kanye West intro.” “As a tongue-in-cheek ‘F*** you!’” Smith adds. “We played live in Orange County a couple of years ago, and our nanny – who’s younger and looks after my two kids when we’re working – came backstage and said, ‘That’s fantastic you did that Kanye West song!’”

Suffer The Children

Originally recorded with producer David Lord at Bath’s Crescent Studios – “David heard the song,” Orzabal recalls, “put about three layers of keyboards on and it was all done!” – this also features Graduate’s drummer, Andy Marsden. It became the band’s debut single and was, oddly, compared to Joy Division by John Peel and NME. “If you listen to the keyboard sound and the actual melody,” Smith argues, “you can tell that it’s influenced by Gary Numan.”

Watch Me Bleed

In hindsight, neither Smith nor Orzabal show much affection for what is arguably The Hurting’s most conventional song. “There are three songs that, every time I think about having to maybe sing live, I cringe, ” Orzabal says. “One is Suffer The Children, the second is Ideas As Opiates and the third is Watch Me Bleed, because it really is one hell of a ‘woe is me’ song.”

Change

Released as a single two months before The Hurting came out, but dismissed as “one of those cheap pop lyrics” by Orzabal in a 1999 reissue, this was originally written for Orzabal’s wife to sing, until Smith heard more potential in it: “I loved the verse. I loved the simplicity of it. Lyrically, it’s nowhere near as deep as other songs but, having said that, you need some levity now and then. It brings balance to the record.”

The Prisoner

Another song inspired by Prisoners Of Pain, this unsettling, provocative track owes a significant debt to Peter Gabriel’s third album. “He would whisper behind the vocal to make it more creepy, and that’s what we did,” Orzabal reveals. “I love this song,” Smith adds. “You go from Change, which is relatively lighthearted, to The Prisoner, which is effectively noise. It’s dark and angry and sad, because of the vocal.”

Start of The Breakdown

Chosen as the album finale for its title as much as how the song closes – “It breaks down a bit,” Smith explains, “which is intentional because of the title. So it’s a falling-apart thing, which we thought was a great ending” – this offers one of Orzabal’s most personal lyrics. “It refers to my father’s nervous breakdown when I was two or three,” he says. “Not a happy song.”

Read more: Top 40 Kate Bush Songs