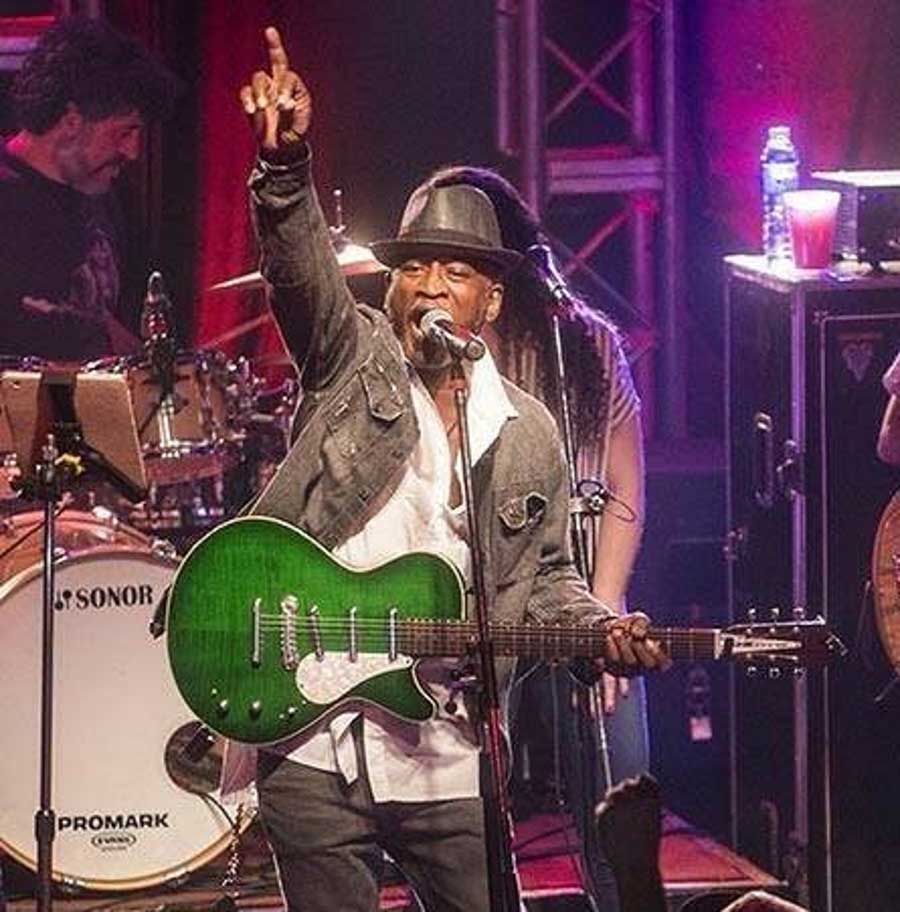

When British reggae was king: Musical Youth were formed in 1979 and still perform today, with just two members – Dennis Seaton and Michael Grant – left from the original line-up

Reggae may have been born in Jamaica, but it grew up in 80s Britain at a time of evolving multiculturalism, finding an unlikely ally in punk and becoming a mainstay in the charts. Classic Pop talks to some of its key players. By David Burke

For such a small island, Jamaica has made a mighty big noise in UK music. Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff and Toots & The Maytals crossed the Atlantic and conquered the former Mother Country in the 1970s. But more than that, they inspired the sons and daughters of an emerging Black Britain to remake the irresistible rhythms of reggae out of their own social and cultural experience, to incubate a uniquely British strain.

Producers Mad Professor and Dennis Bovell – also a member of Matumbi, he anchored Janet Kay’s 1979 hit Silly Games – and bands such as Aswad, Steel Pulse and Misty In Roots, were among the pioneers of this new sound, one that would bleed into the punk and pop movements with The Clash, The Police and Culture Club offering up their own individualistic takes. And, of course, UB40, whose myriad ethnic identities reflected a burgeoning multiculturalism. Their 1983 album, Labour Of Love, was exactly as its title declared – a paean to the reggae songs that were the soundtrack to their childhoods.

As Ali Campbell told Classic Pop in 2018: “The reason we formed a band was to promote reggae and to let people know what dub was. It was the love of my life. I couldn’t understand why people didn’t love it the way that I did.”

Babylon’s burning

Brinsley Forde, the scion of immigrant parents, was searching for his selfhood when he found that “roots music supplied many of the answers”. As he progressed through his teens, Forde became increasingly frustrated playing Jamaican reggae, which he felt had little resonance with his own experience in Blighty.

So the London-born singer began writing and formed Aswad. “The concept was to tell the story from our point of view,” he explains. “I learned of the life in Jamaica from the music. My life was in the heart of London. I could feel the rhythm had a different line, its own melody.”

In their early incarnation, Aswad articulated the Black British story on tracks like Three Babylon and It’s Not Our Wish. Theirs was a variation on roots reggae, and roots reggae was impelled by political awareness. So, was it their objective to become a mouthpiece for young black Britons?

When British reggae was king: Former Here Come the Double Deckers actor and Aswad singer Brinsley Forde MBE

“It would have been presumptuous to believe we would be the voice,” baulks Forde. “Truth is, we had no voice. We went through the British comprehensive system and suffered the injustice of not being educated. I suppose the system educates just a small percentage, leaving the rest ignorant.

“In their ignorance they will forever find it hard to appreciate, understand anything or anyone that is different to their way of life. For young black men, their only relief or sense of pride was provided through sports and music.

“Why were we never told of Lewis Latimer, Garrett Morgan, George Washington Carver, Elijah McCoy, Benjamin Banneker, Otis Boykin, Marie Van Brittan Brown? The list goes on and on of black inventors who have enriched the lives of all races. Would there really be a question of racism if the white race had not set themselves up as givers, providing everything that mankind needed? The truth is very different.”

Aswad did, however, like many British reggae outfits, take a lot of flak from those back in Jamaica for their perceived lack of authenticity. But Forde insists that originally they took their cue from the ancestral homeland, absorbing the music of The Skatalites and Rico Rodriguez (later of The Specials), alumni of the renowned Alpha Boys School.

“Our love of their music led us to pick up instruments in the first place. We copied them to get it right.

“I’m glad to say we have come full circle, telling our side of the story in our own way. Promised Land [by Dennis Brown, which samples Aswad’s Love Fire] is now a standard classic that every reggae and dancehall artist has used.”

They shifted musical direction from roots reggae to lovers rock on the 1981 album New Chapter, and continued to pursue a commercial path with exponential success thereafter, their apotheosis coming with the 1988 UK chart-topping single, Don’t Turn Around. “We all sang, so we were not really a one-dimensional outfit. We didn’t change, we just explored our options,” says Forde of Aswad’s musical metamorphosis.

Crossing further into the mainstream, they appeared alongside Sir Cliff Richard at Wembley Stadium and performed with Sting, before Forde quit in 1996 for what were ambiguously referred to at the time as “spiritual reasons”.

Well over two decades on, he remains vague about the reason for his departure – “We all have a path to follow in life and 1996 presented a fork in the road.”

There was, though, a brief reunion in 2009 for the 50th anniversary of Island Records. And happily for Aswad fans, Forde doesn’t rule out returning to the band – now fronted by founding member Drummie – on a more permanent basis. “We never say never. Doors are open on both sides. When the right time comes, it won’t be a problem.”

Black steel in the hour of chaos

Contemporaries of Aswad, Steel Pulse came out of the Handsworth area of Birmingham. Formed by friends David Hinds and Basil Gabbidon, they were an integral part of the Rock Against Racism movement.

Gabbidon, who was born in Buff Bay, Jamaica, and moved to Britain’s second city at the age of nine, grew up during the era of heavy rock and was exposed to Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple at college. Other formative touchstones included The Jackson 5 and The Isley Brothers – reggae didn’t appear on his radar until he heard Niney’s Blood And Fire and then Bob Marley & The Wailers’ Catch A Fire.

“It didn’t really click with me before then. Catch A Fire had guitars on it – guitar solos!” he recalls, still audibly excited all these years later.

“And the production was more than you used to get with simple Trojan records. It looked as if they were taking reggae seriously. I thought, yeah, I could get into this.”

When British reggae was king: Basil Gabbidon was a founding member of Steel Pulse

When it came to establishing their singularity, Steel Pulse drew on both rock and reggae influences equally. “I would call what we were doing, industrial reggae,” says Gabbidon. “You could almost hear the clang and the clatter of the British way of life – slightly more metallic, less warm. And the name Steel Pulse kind of worked really – it was the sound of steel.”

They paid their dues in pubs favoured by Jamaican ex-pats, not all of whom appreciated how the youngsters were trying to reimagine the music.

- Read more: The story of 1981 in music

“It didn’t necessarily go down that well unless we did something popular, like a John Holt tune. There were some places we played and we were told to get off the stage – ‘Play some proper music!’ They didn’t understand where we were coming from.”

But one bunch of people that did understand where Steel Pulse were coming from was the punks, who embraced reggae for its outsider-dom as much as for its banging tunes. Don Letts, disc jockey, filmmaker and former member of Big Audio Dynamite, would play reggae records at punk haunt the Roxy.

The Sex Pistols’ Johnny Rotten cited Dr Alimantado’s Born For A Purpose as a favourite record and was appointed talent scout for Virgin Records’ Front Line reggae imprint. And The Clash charted with their version of Junior Murvin’s Police & Thieves, while their (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais was penned about their experience at a reggae dance.

“The punks were against the system,” says Gabbidon. “They saw that reggae was against the establishment, Johnny Rotten especially. He used to walk around with a Steel Pulse badge on his jacket.

“We helped each other, helped to make each other legit. But one thing we didn’t like was, when we would play punk gigs, some of the people would spit. That wasn’t a cool thing. Not all the punks liked it. I know The Stranglers didn’t like it. We didn’t tolerate it.”

Rock against racism

Reggae and punk united under the Rock Against Racism banner, a response to the rise in racism on Britain’s streets, increasing support for the far-right National Front and Eric Clapton’s drunken rant at a concert during which he expressed support for Enoch Powell. Ironically, Clapton had previously taken Bob Marley’s I Shot The Sheriff to No.1 in the States.

“Rock Against Racism brought a camaraderie among different types of music and bands of that era,” remembers Gabbidon. “It brought us together.”

Steel Pulse fought the power on Ku Klux Klan and Prodigal Son from the incendiary Handsworth Revolution, their debut collection on Island Records. They were signed to the label despite Chris Blackwell’s reservations.

“I always wanted to go with Island. We wanted autonomy over our music. Chris Blackwell wasn’t sure at first. But we were signed up by one of his associates after we supported Burning Spear and blew the place away. We dressed different, we performed different, and she signed us up straight away, more or less, after we came off stage. Chris Blackwell was away in America and he wasn’t sure about us because we were British. He must have thought we were a bit soft or something! But he was very happy once things kicked off.”

And kick off they certainly did, as Steel Pulse broke through in America and supported Bob Marley & The Wailers on a European tour. The bigger venues – a far cry from the hostelries of the West Midlands – were daunting to Gabbidon.

- Read more: 40 years of 2 Tone

“You’d play a note and it came back a second later! We had three nights in Paris on the same tour and I was able to absorb the whole thing – the mass of people, the lights, everything. That was really exciting.

“What I learned from Bob on that tour was about performing – not to give up when you’re down. One thing about Bob – and Buju Banton, for whom I played guitar a few years ago – was no matter how much pain they were in, or if the band wasn’t playing well, they always performed as if it was their last gig.”

Gabbidon left Steel Pulse after four albums, just missing out on their 1986 Grammy for Babylon The Bandit. “I was exhausted. I started the band and I was doing all the running around from the very beginning. I just got worn out, basically. I was having dark dreams and stuff like that. It was a constant back and forth and there was no time to develop the music.

“That’s why Handsworth Revolution has a different sound to the other albums. You could feel it growing out of the ground. It’s very organic. To do that you need to get back to your people, get back to your own yard, and we weren’t able to do that enough.”

David Hinds is still at the helm of Steel Pulse, while Gabbidon maintains a largely live profile in Birmingham and beyond.

“I just see myself as an ordinary guy, like everybody else, but people say to me that we changed a lot of people’s lives. I know we’ve had an influence. In a sense, we were one of the first reggae bands to come out of Birmingham, and then others followed like Pato [Banton], UB40, The Beat, Musical Youth. Birmingham became the centre of reggae. I feel good about Steel Pulse. We were at the beginning of a wave. We were pioneers, I suppose.”

Youth culture

Pioneers whose success provided the impetus for a quartet of Brummie schoolkids to make their own tilt at the big time. Musical Youth already possessed some pedigree – Junior and Patrick Waite’s father had been in Jamaican rocksteady crew The Techniques, who enjoyed a string of local hits in the 60s. A second pair of siblings, Kelvin and Michael Grant, completed the line-up, before Dennis Seaton was drafted in on vocals.

Musical Youth cut their teeth in West Indian working men’s clubs up and down the country, but never let their aspiring career get in the way of their education.

“School was very important to us all, and the education authorities ensured that we attended with the minimum of fuss. We were only allowed to work 49 days out of the school year, due to us being minors,” explains Seaton.

When British reggae was king: Musical Youth in 2019

An appearance on John Peel’s BBC Radio 1 show secured them a contract with MCA Records – and then, in 1982, came Pass The Dutchie, their adaptation of Pass The Kouchie, a song by The Mighty Diamonds. It went to No.1 in the UK, selling four million-plus copies, and No.10 in the US, where it was also nominated for a Grammy Award.

The “kouchie” that The Mighty Diamonds sang about was Jamaican slang for a pot that held marijuana – Musical Youth’s “dutchie” was a rather more innocent cooking pot. They subverted the lyric with the refrain, “How does it feel when you’ve got no food?” – a question that was all too relevant in Thatcher’s Britain.

After a couple of minor hits, their move away from reggae into R&B terrain arguably did for Musical Youth – as did friction over finances and personal problems. By 1985, Seaton had had enough.

“I became a born again Christian and, after an ill-fated tour of the Caribbean, I became disillusioned with the band and its direction. They wanted to play as many gigs as possible, but with the work restrictions and an inexperienced manager, this didn’t help our growth.”

He embarked on a brief solo career, worked in the car rental industry and earned a music degree. Plans to reform Musical Youth in 1993 were halted following the death of Patrick Waite from a heart condition at the age of just 24, while he was awaiting a court appearance on drugs charges.

“I was aware of Patrick’s problems. When I finally got to speak to him it was a very sombre moment as that was our last conversation,” says Seaton.

“The good thing is that I had encouraged him to get back to playing his bass. Patrick was a quiet member of the band. He was a true friend who would follow you to the end of the earth. For his age, he was one of the best bass players in the world.”

Seaton and Michael Grant reconciled in 2003, and have recorded a brace of albums as Musical Youth since then, including 2018’s When Reggae Was King.

“For over 40 years, British reggae has turned a generation into reggae lovers,” declares Seaton of the impression left by Aswad, Steel Pulse and Musical Youth.

“It changed the face of the British music scene and it’s rare to find anyone who doesn’t have a special place for reggae in their hearts and their record collections. It’s unfortunate that the current popular radio stations and our record labels don’t support it as they did in the past.

“Even the Grammy Awards has a section for reggae, but not our own BRIT Awards. Fortunately, reggae is a world heritage, so it will be preserved forever – and I must say amen to that!”

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.