The Police Interview: ‘Being in The Police was like wearing a Prada suit made out of barbed wire’

By John Earls | March 4, 2020

Making Liam and Noel Gallagher look like The Chuckle Brothers, The Police were pop’s most famous brawlers, somehow making five iconic albums despite the hatred. They still loathed each other while making billions on their 2000s reunion tour. Or that’s the myth. What was life really like among the warfare? Stewart Copeland and producer Hugh Padgham recall crisis meetings, unlikely classics and… jogging trampolines? It’s a story even odder than the legend…

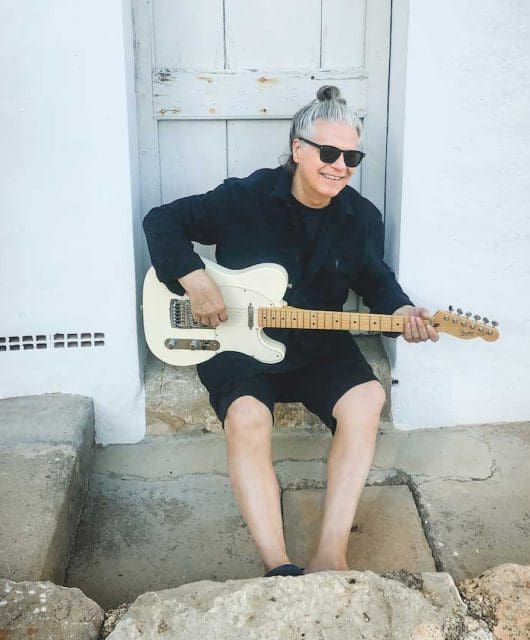

When Sting and Shaggy played in Los Angeles recently on tour for their joint album 44/876, sat in the front row together were Sting’s old bandmates Stewart Copeland and Andy Summers. All three of The Police in the same venue: over a decade since their reunion tour, does this mean another comeback is on the way? Er, not quite… “We sat in the audience so that we could make snide comments, watching him from the front so he could see us,” guffaws Stewart delightedly. “He’s pretty fucking good on stage, old Stingo.”

That year of reunion shows in 2007-08 was the third-highest earning tour of all-time, grossing £280 million. But it also saw one of music’s most infamously brittle bands bitch and moan about each other pretty much from day one. Could they bear to do it again? “There’s no reason why not,” considers Stewart. “We all get along really well and we’re all still in fine fettle. The songs are still really great! I’d be surprised if somebody doesn’t have a bright idea for how to do it sometime in the future, but it’s certainly not what anyone is thinking about now.”

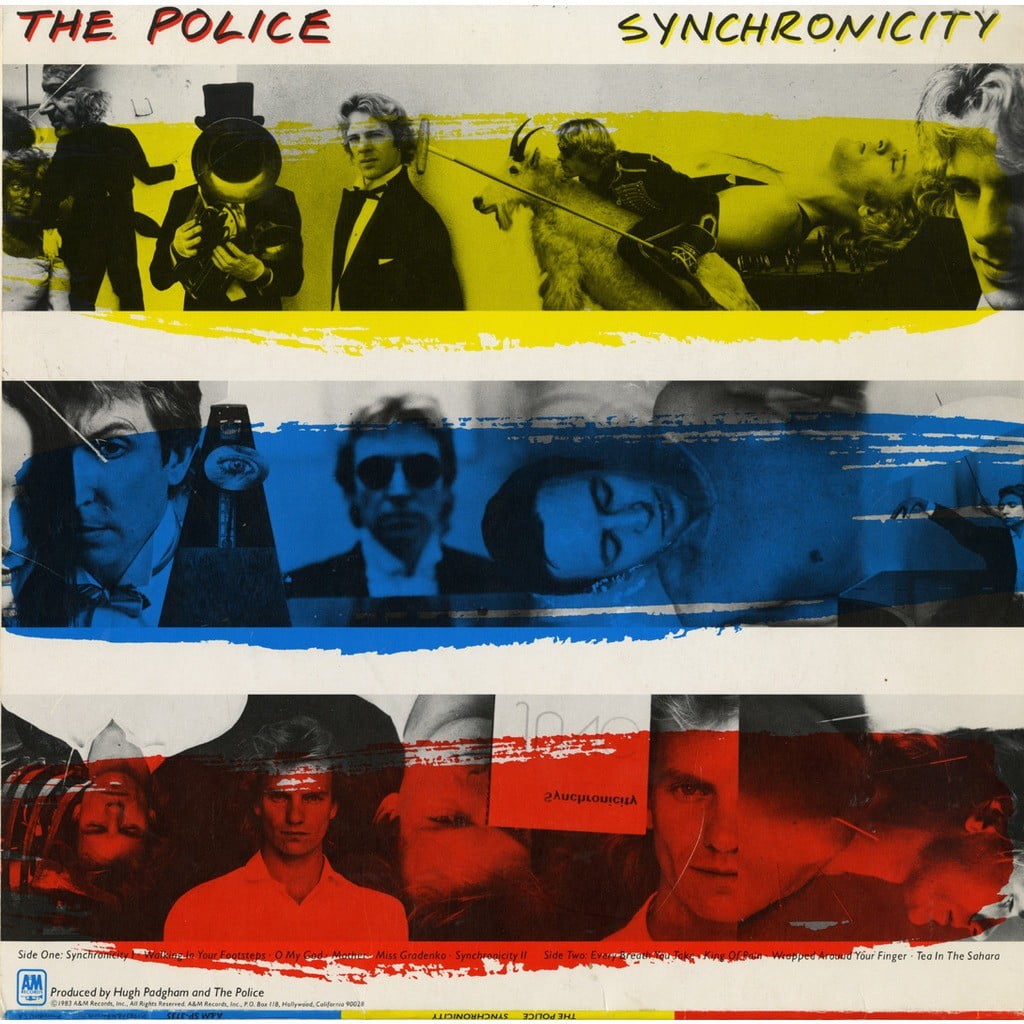

That’s as close as Stewart Copeland ever gets to being diplomatic about The Police. After all: “We all get along really well?” What? Sting, Stewart Copeland and Andy Summers get along? The same Police who loathed each other so much that their final album Synchronicity is the accepted benchmark of making a classic despite eternal hatred? “Sure,” insists Stewart. “Since we’ve been through the wars together and we don’t have any reason to fight anymore, we get on great.”

Stewart saw Andy the week before our interview in early November; Sting a couple of weeks before that. He delights in taking the piss out of Sting but, 40 years after losing the fight to be The Police’s pre-eminent songwriter, Stewart has a great affection for “old Stingo”, saying: “The English tabloid version of Sting? Sting is so far from that guy. As a rock star, Sting may appear a bit prim and earnest. But let it be known, Sting is not that guy.”

So everyone is all pals really. But Stewart is keenly aware that’s not what people think of The Police. “The avatar of The Police is that we fought all the time, and I understand that, because it’s an interesting story,” Stewart accepts. “The truth is, we fought very little. There was a lot of tension in our last two albums, but we weren’t fighting. Over dinner, we’d still shoot the shit and hang out. But in the studio, we were icily formal, mournful over the loss of our band’s camaraderie. It wasn’t open warfare, it was tension.”

So everyone is all pals really. But Stewart is keenly aware that’s not what people think of The Police. “The avatar of The Police is that we fought all the time, and I understand that, because it’s an interesting story,” Stewart accepts. “The truth is, we fought very little. There was a lot of tension in our last two albums, but we weren’t fighting. Over dinner, we’d still shoot the shit and hang out. But in the studio, we were icily formal, mournful over the loss of our band’s camaraderie. It wasn’t open warfare, it was tension.”

That tension was never more bitter than when recording Every Breath You Take. In May, it became the most-played song ever on US radio, overtaking The Righteous Brothers’ You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling. It’s been aired over 15 million times in the US alone, but nearly never got made at all. You could make a 10-part Netflix documentary about Every Breath You Take, from the moment Sting’s demo was first played at Utopia Studios in Primrose Hill, North London, to the rest of the band, plus manager Miles Copeland and Hugh Padgham, The Police’s producer since fourth album Ghost In The Machine. “We knew it was a hit as soon as we first heard Sting’s platinum demo,” raves Stewart. Hugh remembers being told by Miles at the playback: “There’s a goddamn hit if I ever heard one! Don’t fuck it up, Hugh!” The producer admits it would have been hard to fuck it up, noting: “I really think if my pet dog had produced Every Breath You Take, it would have been a hit.”

He Bangs The Drums

He Bangs The Drums

The problems over recording Every Breath You Take arose precisely because it was so simple. Hugh explains: “If Stewart couldn’t be The Police’s hit writer anymore, he wanted to show off his drumming skills. And he couldn’t show off on Every Breath You Take.” The secluded Le Studio in Quebec, where Synchronicity was mixed, was so remote the only distraction was to go skiing. Sting would go in the morning, leaving Stewart with Hugh. But in the afternoon, singer and drummer would swap mixing duties. Hugh recalls: “One morning, Stewart came in and said, ‘I’ve got an idea. I want to overdub a hi-hat on Every Breath You Take.’ We got the hi-hat out, it’s played on the song, Stewart goes skiing at lunchtime and Sting comes in going, ‘OK, what fucking rubbish did you do this morning?’ Everything Sting said about Stewart had an ‘F’ in front of it. I played him the new mix of Breath with the hi-hat and Sting went, ‘That’s fucking awful, get rid of it.’ I told him, ‘If you don’t like it, shouldn’t you talk to Stewart about it?’ The response came: ‘No. It’s my song. I hate it. Get rid of it. Now.’ In those analogue days, if you got rid of something, it went to the great magnet in the sky. Sting stood over me, making sure I put the hi-hat track into the tape machine and wiped it. And of course, Stewart comes in the next day going, ‘Where’s my fucking hi-hat?’”

Hugh’s sympathies mostly lay with Sting by the final stages of Synchronicity. “It wasn’t that I wanted to take Sting’s side over anyone else,” emphasises Padgham. “I did it because I agreed with him. The problem with overdubbed hi-hats is that they often sound like overdubbed hi-hats, rather than anything necessary to the song. We needed to get the album finished and if the overdubs had got out of control, Synchronicity would have been like Brexit and never happened. It meant that, by the end of that album, I was not on Stewart’s Christmas card list. We’re fine now – I met up with them on the reunion tour, and Stewart is one of the loveliest, friendliest people there is.”

Stewart is quick to praise Andy Summers’ role in Every Breath You Take, too, noting: “The demo was obviously a hit, but it was nothing like the current version, as Sting was singing the chords over a Hammond organ. Andy went, ‘Guys, hello? We’re a guitar band?’ Andy is truly clever with harmony and worked out the song’s arpeggiated guitar figure. One of our favourite in-band riffs is that, when Puff Daddy sampled Every Breath You Take on I’ll Be Missing You, he sampled Andy’s guitar figure, not the melody or the lyrics. Me and Andy go, ‘Go on Sting, pay Andy his royalties’ and Sting will say, ‘OK, Andy, here you are’… not reaching anywhere near his wallet.”

Stewart is quick to praise Andy Summers’ role in Every Breath You Take, too, noting: “The demo was obviously a hit, but it was nothing like the current version, as Sting was singing the chords over a Hammond organ. Andy went, ‘Guys, hello? We’re a guitar band?’ Andy is truly clever with harmony and worked out the song’s arpeggiated guitar figure. One of our favourite in-band riffs is that, when Puff Daddy sampled Every Breath You Take on I’ll Be Missing You, he sampled Andy’s guitar figure, not the melody or the lyrics. Me and Andy go, ‘Go on Sting, pay Andy his royalties’ and Sting will say, ‘OK, Andy, here you are’… not reaching anywhere near his wallet.”

Every Breath You Take inspired the title of The Police’s new boxset Every Move You Make, which rounds up all five albums plus a B-sides compilation. Stewart admits he’s not played a Police album in full “since July 1983, or whenever it was that we’d finished mixing Synchronicity.” But he’s proud of how his band’s music has aged. “We made great records, despite the fact it wasn’t very comfortable to make them,” asserts Stewart, 67. “It’s only now that we understand what our conflict was about and acknowledge that everyone’s point of view was valid. And we had a very strong work ethic. Nobody ever shirked, nobody stayed at home. All three of us were always leaning forward – and that’s the personality in each of us that led to the conflict: one person was anointed the god of all music, while the other two were still pushy sons of bitches. In amongst all that tension, there was always a positive attempt to make it work.”

Hot Fuzz

Hot Fuzz

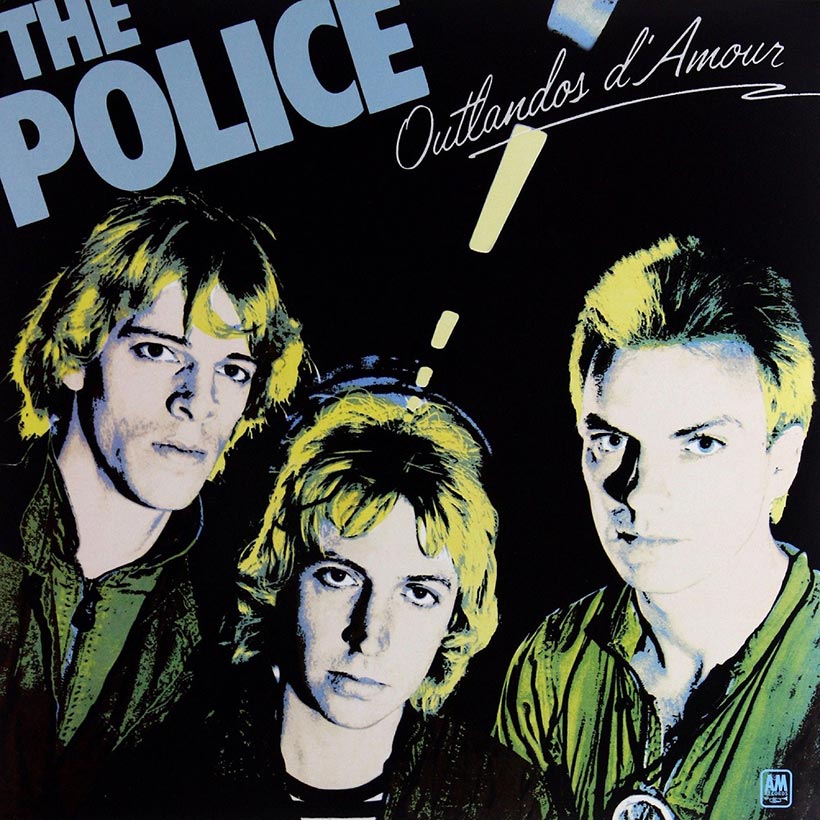

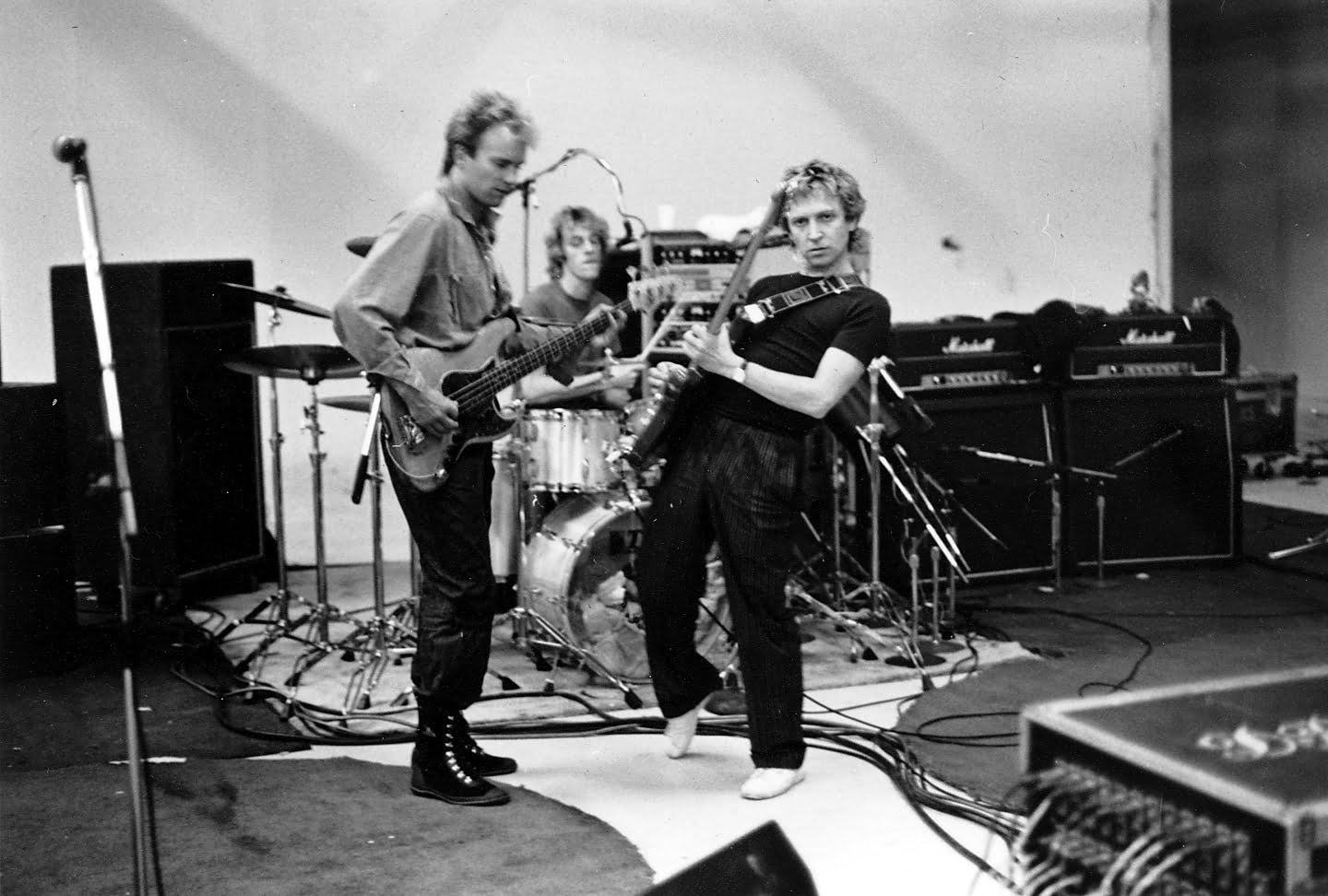

The Police’s story could have been very different. Stewart and Sting formed the band in 1977, when the singer/bassist moved to London and met Stewart for a jam session. They’d first met when the drummer’s old band, cult prog-rockers Curved Air, played in Newcastle on tour. Another former progger, guitarist Henry Padovani, was persuaded to cut his long hair and shave his beard off to fit in with the punk look. Andy, a decade older and a veteran guitarist for Eric Burdon and Kevin Ayers, quickly joined, too. “It was Andy who told me Henry didn’t fit,” recalls Stewart of Henry’s dismissal. “I didn’t believe him, but he was right.”

With just three people in the band, Stewart believes, “it gives everyone lots of room, while also requiring a great deal from everyone. With three musicians, you don’t step on each other’s territory.”

It’s easy to forget now, but Police classics Roxanne, Can’t Stand Losing You and So Lonely flopped when first released as singles. “We weren’t discouraged when those early singles failed,” Stewart insists. “Most bands assume they’ll make it, or else you wouldn’t be doing it. We had that same arrogance and youthful optimism. We were too young to be impressed at the great tenacity A&M Records had in sticking with us.”

Roxanne finally became a hit in the summer of 1979, when The Police were starting to get noticed on their first US tour. It charted when The Police were already booked to support comedy band Alberto Y Lost Trios Paranoias on tour. “When we came back from the States, we had no idea it had kicked off,” remembers Stewart. “We didn’t have any security, and there was a mob out there on the first show. Being mobbed was exciting, but our success was incremental. There was never a point where it suddenly got so big that we went, ‘Wow!’ For us, the first milestone was playing Dutch festival Pinkpop in ’79. We were on early in the afternoon, but we tore that place over and left it a smouldering ruin. We knew that it was a show to remember, if only for ourselves.”

Roxanne finally became a hit in the summer of 1979, when The Police were starting to get noticed on their first US tour. It charted when The Police were already booked to support comedy band Alberto Y Lost Trios Paranoias on tour. “When we came back from the States, we had no idea it had kicked off,” remembers Stewart. “We didn’t have any security, and there was a mob out there on the first show. Being mobbed was exciting, but our success was incremental. There was never a point where it suddenly got so big that we went, ‘Wow!’ For us, the first milestone was playing Dutch festival Pinkpop in ’79. We were on early in the afternoon, but we tore that place over and left it a smouldering ruin. We knew that it was a show to remember, if only for ourselves.”

It’s The Police’s second studio LP that ranks as Stewart’s personal favourite. ”Reggatta de Blanc might not be our greatest album, but it was the most fun to make, even though Sting only had 20 minutes to write it after the raging blaze of touring. The quality and inspiration were at their height and it doesn’t take 20 years to write three notes as perfect as the chorus of Don’t Stand So Close To Me. Our collaboration as a band was at its most fruitful and we were in our most creative phase,” Stewart explains.

Reggatta de Blanc and its predecessor Outlandos d’Amour were made above a dairy in Leatherhead, Surrey, with former doctor Nigel Gray producing. An eccentric who went on to produce Siouxsie And The Banshees before retiring in 1987, Nigel was an amateur who built his own Surrey Sounds studio. “Nigel was a great referee,” Stewart recalls. “Nigel would have had a much tougher job keeping us playing nicely on the later albums, but he was great at the human part – making sure all three voices were heard and having us enjoy the studio process.”

One Artistic Truth

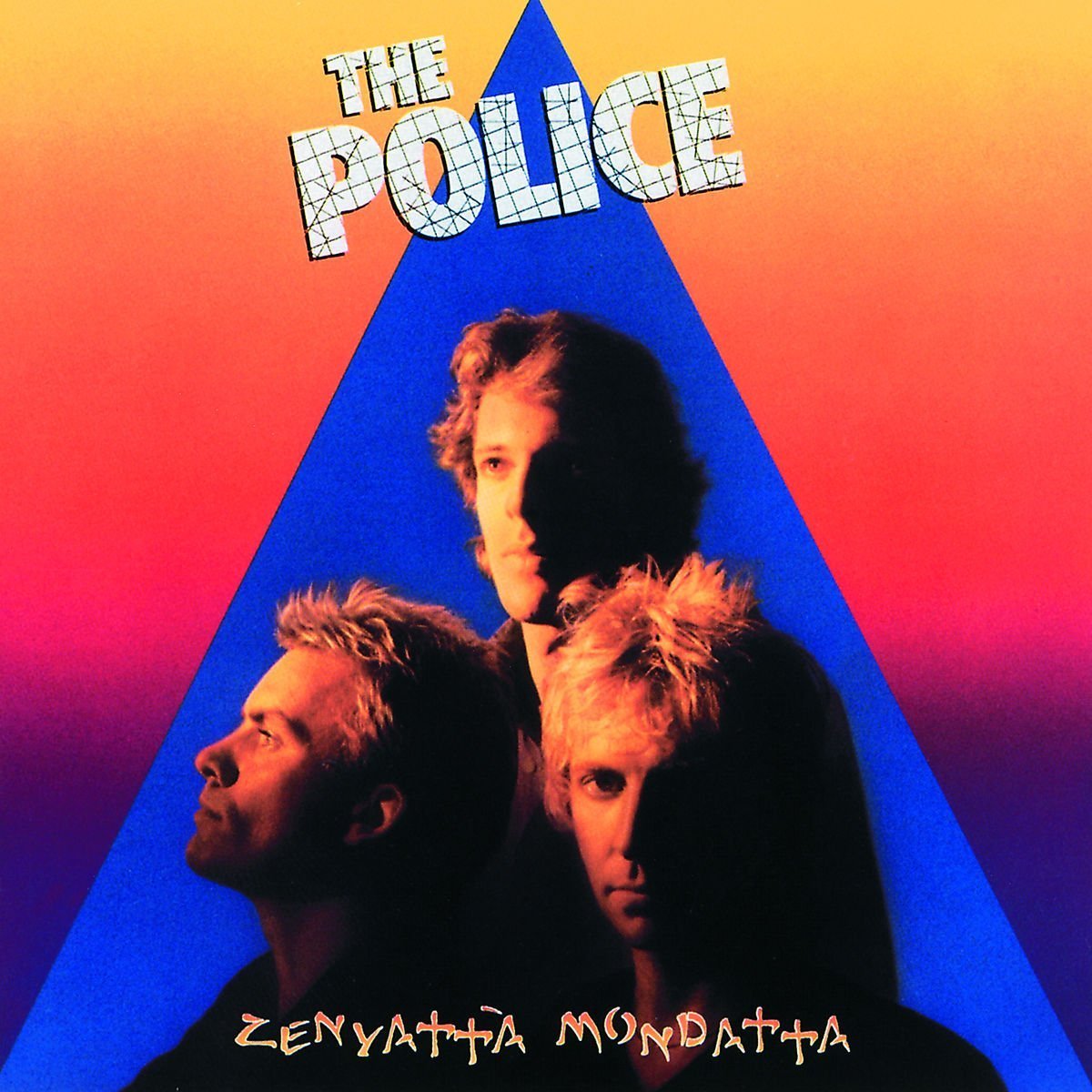

By third album Zenyattà Mondatta, tensions were rising. Made in the Netherlands for tax purposes, Stewart says: “By Zenyattà, Sting was very clear in his mind what The Police’s music should be. He’s pretty darned clever in his vision but, for Sting, there’s only one artistic truth. All his creative juices tell him this, but the other two mortals in the room also had their musical truths. The person writing those fantastic songs had every right to develop fully-fledged ideas of what the music should be, but the others should have got to mould the result, too. It was manageable on Zenyattà, but the wrong motives started to be assigned to each other: one person imagines the other is trying to smother them out of existence, while the other imagines the other guy is just jealous and trying to intrude.”

Keeping up their album-a-year output, it was time for a change of producer for 1981’s Ghost In The Machine. Hugh Padgham had been recommended to Sting by Andy Partridge after producing XTC’s album English Settlement. “Good three-piece bands always really excite me,” says Hugh. “The same as everybody, when I first heard Roxanne, I went, ‘Christ, what’s this?!’ I loved the simplicity of their albums before I worked with them. They sounded great, especially as they were made for two-and-sixpence. They wanted a change from Nigel, firstly as they wanted to expand their music and also because Nigel was a bit of a bad influence. Even though he was a qualified GP, Nigel introduced a coke problem. When Miles Copeland rang my manager to see about me working with The Police, his first question was, ‘Does Hugh do drugs?’”

Keeping up their album-a-year output, it was time for a change of producer for 1981’s Ghost In The Machine. Hugh Padgham had been recommended to Sting by Andy Partridge after producing XTC’s album English Settlement. “Good three-piece bands always really excite me,” says Hugh. “The same as everybody, when I first heard Roxanne, I went, ‘Christ, what’s this?!’ I loved the simplicity of their albums before I worked with them. They sounded great, especially as they were made for two-and-sixpence. They wanted a change from Nigel, firstly as they wanted to expand their music and also because Nigel was a bit of a bad influence. Even though he was a qualified GP, Nigel introduced a coke problem. When Miles Copeland rang my manager to see about me working with The Police, his first question was, ‘Does Hugh do drugs?’”

Transforming their previous miserly recording budget, Ghost In The Machine was made at George Martin’s studio AIR in Montserrat. “With hindsight, we know our strife wasn’t all that bad,” laughs Stewart. “At the time, it felt harsh and diabolical. But the results are great records we’re all very happy with. And the truth is, it wasn’t that diabolical. Being in The Police was like wearing a Prada suit made out of barbed wire.”

Expanding the sound meant horns and keyboards were suddenly all over songs such as Too Much Information and Rehumanize Yourself. “When Sting pulls out an instrument, something really cool will happen,” acknowledges Stewart. “When he first pulled out an oboe on tour, that had a cool feel, because he was only playing a couple of notes. But, because Sting should have been drowned at birth, five minutes later, he’s playing 20 notes. Thankfully, the sax is easy to play and there’s no disputing that what Sting played on Ghost In The Machine is all really cool parts.”

Hugh describes the atmosphere on Ghost In The Machine as “pretty good – a bit of healthy bickering”, apart from trying to make Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic. “Whatever we tried to record didn’t work,” recalls Hugh, also famed for his work with Genesis, David Bowie, The Human League and creating Phil Collins’ gated drum sound on In The Air Tonight. “We tried reggae, full-on rock, faux-reggae, whatever. It was the one track not gelling – we used the demo as the backing in the end. Stewart did an amazing job because, without a click-track to follow, he was able to put drums over the already-recorded demo and make it sound incredibly vital.”

The album gave Hugh his first taste of Sting’s unusual approach to recording. “Sting thought the studio was creatively boring, so he’d want to do everything as quickly as possible,” Hugh explains.

The album gave Hugh his first taste of Sting’s unusual approach to recording. “Sting thought the studio was creatively boring, so he’d want to do everything as quickly as possible,” Hugh explains.

“’Slapdash’ isn’t quite the word I’d use, but he didn’t mind mistakes. It didn’t happen very often, but if he sang out of tune, he’d always growl, ‘Why?’ when I said, ‘We need to do that line again.’ He’d make me play it back to him, me thinking, ‘Why don’t you just do it again?’ The other thing that was quite irritating was Sting’s jogging trampoline.”

Ah, Sting’s jogging trampoline. A brief early-80s fad, the jogging trampoline was 3ft across and simulated running when the ‘bouncee’ attached sandbags to their arms and feet. This was before treadmills, OK? You can see Sting bounce about on his jogging trampoline in the Synchronicity tour film. “At shows, it looked like a punk-pogo,” says Hugh. “But Sting wanted to use it in the studio, too. You’d think that, recording an album, you’d want your bass to sound as clean as possible. But no, Sting wanted the vibe. Which I understand, but it meant he was jumping up and down on a trampoline, when the studio floor at AIR was sprung anyway. The whole bloody floor was jumping up and down and I’d be thinking, ‘Christ, the tape recorder isn’t liking this!’ Because Sting was jumping up and down, there’d be mistakes in his playing. In those days of 24-track studios, you’d either have to force Sting to do it again or, if he wasn’t around, I’d have to get his bass roadie Danny Quatrochi to punch it in.”

Ghost Busting

And then came Synchronicity. Stewart graciously accepts Sting didn’t need to make The Police’s fifth album. “By Ghost In The Machine, we’d got as big as we were ever going to get,” he admits. “Sting very generously stuck it out for one more album than he had to. For our career, we broke up at exactly the right time. We didn’t see the other side of the parabola.”

Which is easy to say now. In 1982, literally nothing had been recorded in the first fortnight of making Synchronicity. Miles Copeland flew over for a crisis meeting. “It was shocking,” says Hugh. “I wasn’t used to such incredibly babyish behaviour. Sting and Stewart were infantile. Poor old Andy was left piggy-in-the-middle, though he could be pretty grumpy himself. It was scary, too, because it was my job to get the record made.”

The emergency meeting was held at AIR’s swimming pool. As Stewart says of their surroundings: “We were in paradise, creating our own hell. But in the bitter despond of that trench warfare, we could all hear that this music was fucking great.”

For Hugh, the arguments are partially what makes the album so good: “Side one, where the fast songs are grouped together, has an incredible energy, which I think was borne out of anger.” He credits Sting for the precision of songs like King Of Pain and Wrapped Around Your Finger, enthusing: “We’d mute out parts so the chorus comes in bigger as a contrast and to make songs breathe more. I give Sting huge credit for that, as it was mainly me and him mixing in Quebec.”

For Hugh, the arguments are partially what makes the album so good: “Side one, where the fast songs are grouped together, has an incredible energy, which I think was borne out of anger.” He credits Sting for the precision of songs like King Of Pain and Wrapped Around Your Finger, enthusing: “We’d mute out parts so the chorus comes in bigger as a contrast and to make songs breathe more. I give Sting huge credit for that, as it was mainly me and him mixing in Quebec.”

Although The Police re-recorded Don’t Stand So Close To Me and De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da in 1986 for a hits compilation, there’s been no new music since Synchronicity. Stewart doesn’t believe there should be, after an abortive attempt during the reunion tour. “What made the reunion tour worthwhile was seeing the effect we had on the audience,” summarises Copeland. “So long as the audience went crazy, there was a good reason for us to take each other’s bullshit: ‘This is why I put up with you, motherfucker.’ Going into a studio, there’s none of that. Rehearsing was bad enough, but at least we know how Message In A Bottle goes. Any arguments, you’d check the record: ‘What people have paid $300 for sounds like that, so that’s what we’re going to do.’ End of argument. A new record? No audience, no affirmation, no reward. Just hell on earth.” The Police like their Prada suits a little more comfy these days.