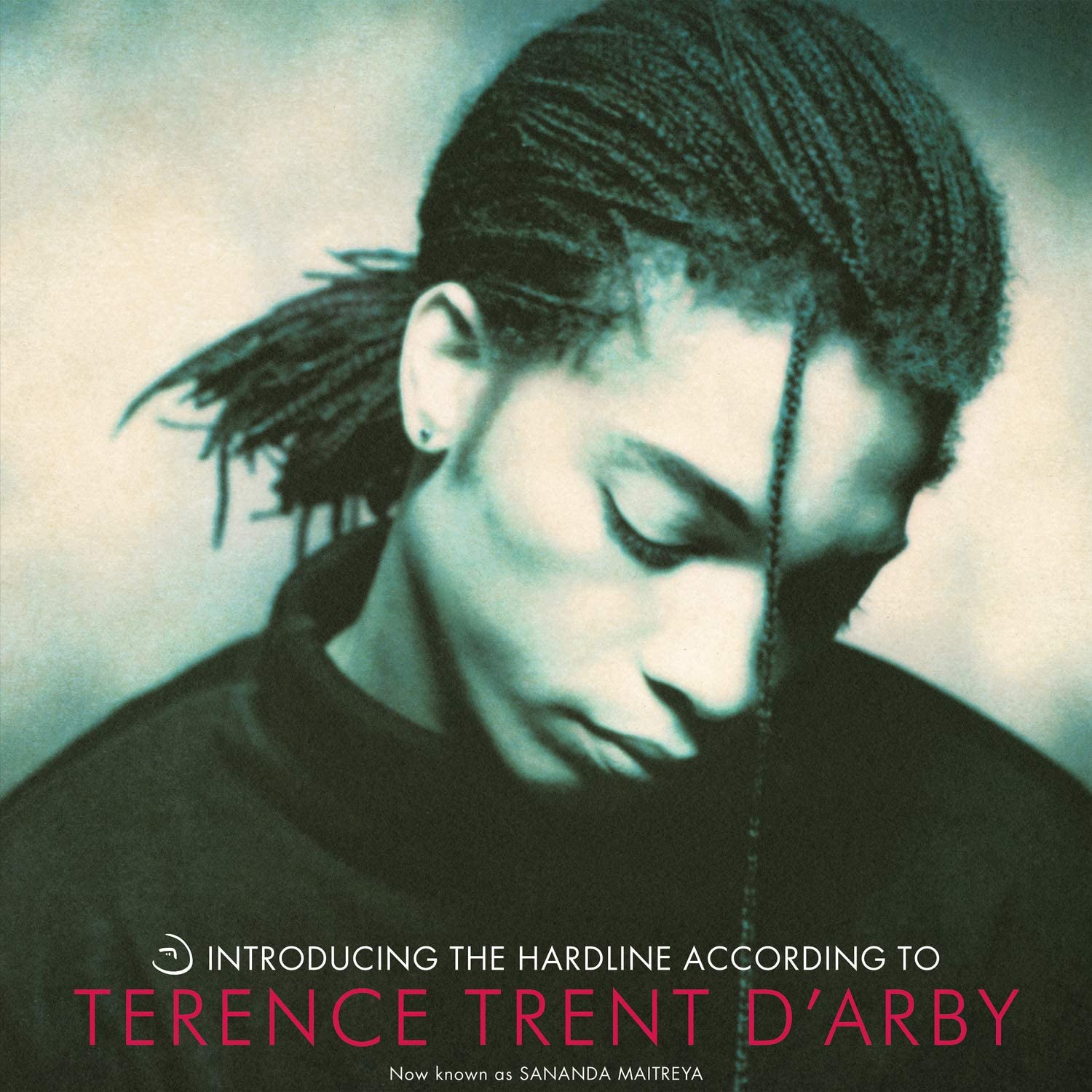

Introducing The Hardline According To Terence Trent D’Arby cover

Introducing The Hardline According To Terence Trent D’Arby saw the singer hyped as one of the 80s brightest stars. However, any potential he had was lost when he appeared to believe the hype more than anyone else…

Time has decreed that 1987 was a monumental year for our male pop superstars with the holy triumvirate of Michael Jackson, Prince and George Michael all delivering career-defining opuses in Bad, Sign O’ The Times and Faith respectively.

One name frequently omitted yet worthy of inclusion in the list of that year’s incredible albums is Terence Trent D’Arby, at the time one of the brightest hopes of the music scene, whose debut album, Introducing The Hardline According To Terence Trent D’Arby matched his peers in terms of quality and success.

A one-man amalgamation of the artists he had been inspired by, Terence’s arrival on the scene was initially met with trepidation.

With a raspy, soulful voice that could seamlessly evoke Stevie Wonder, Sam Cooke and Otis Redding, a stage presence which alluded to James Brown and Mick Jagger, an androgynous visage akin to that of Prince and a backstory that placed him as a former boxer and soldier, many questioned whether he was indeed too good to be true.

He had been born in 1962 to a Minister father and teacher mother, both of whom sang gospel in church and encouraged young Terence to do the same.

When he got older, Terence, disillusioned by his strict religious upbringing, escaped first by going to college to study journalism, then training as a boxer before enlisting in the US Army.

After a short spell in Oklahoma, Terence was posted overseas to Frankfurt’s Third Armored Division, the same outfit Elvis Presley served at in the 60s.

It was while in Germany that Terence began his burgeoning career as a musician. He threw himself into Frankfurt’s vibrant bustling live music scene, eventually finding himself as the frontman of a band called Touch, which he described as “Earth Wind & Fire-meets-The Who”.

As his career in music progressed, Terence was unsuccessful in his request to be discharged from the army and forced to go AWOL. He spent his days hiding out in friends’ apartments and record shops and at night performed in clubs.

While touting Touch’s demo tape, Terence met Klaus Pieter Scheinlitz, a press officer at a German record label, who mentored the singer, introducing him to an expansive range of musicians and becoming his manager, trying to secure a record deal for Touch.

However, with Terence still obligated to fulfil his army duties, a lengthy battle ensued to get him released. He was eventually discharged from the army in April 1983 and free to pursue his music career.

Relationships within Touch were strained (“There was a lot of jealousy in the band,” Terence told Rolling Stone in 1988. “I was the frontman, and to be honest, I just wanted to be a star – I wanted a fast car and fast women. I just wanted to shake my butt onstage and get laid.”), the band broke up and Terence and Klaus moved to London.

Following a spell in another band, The Bojangles, a headstrong and focused Terence decided he would prefer to be a solo artist, eventually landing a deal with Columbia Records.

Beginning work on his album, Terence had already written a wealth of material and was clear in what direction he wanted to head.

However, recognising his inexperience, Columbia paired him with Heaven 17’s Martyn Ware, who had been working as a producer and helmed Tina Turner’s career-relaunching Private Dancer album.

Looking for his next project, Martyn had refused offers to produce records for Rod Stewart and Bette Midler, opting instead to work with new artists.

“I was actually just about to do another weird soul project when this tape landed on my desk from a new A&R man at Sony,” Martyn recalled to Emma Warren at the Red Bull Music Academy. “It was this tacky tape and it said Terence Trent D’Arby on it and I put it on.

“I’m literally about to sign the contract on doing this other artist and I put it on and went: “This is absolutely fantastic!” It was a bit rough, but the songs were incredible and the voice is incredible. So, I went down there and managed to persuade them that I should do his first album.”

Martyn and Terence hit it off immediately, both sharing a vision of what they wanted to achieve with the album, taking the honesty and authenticity of old-school rock and R&B and updating it so that it was soul music, but modern and not derivative of what had gone before.

Martyn was particularly impressed, not only with Terence’s immeasurable talent, but also his work ethic.

“We got on like a house on fire,” he says. “He used to come into the studio at least an hour before I got in. And he used to play Sam Cooke tunes and Otis Redding, and he sat there studying, as though he was studying a university subject.

“He used to study them in darkness, in the studio, listening to them, singing along to them, and saying: ‘This might be my only chance, this album, to try to get out what I’ve got inside me’. And he really wanted to know his subject thoroughly.”

As the recording sessions were coming to an end in March 1987, Terence’s career was launched with the release of his debut single If You Let Me Stay (one of the two tracks on his album not produced by Martyn).

A slice of uplifting soul just on the right side of retro, the record company were delighted when the single reached the Top 10 and, confident in the talents of their new artist, decided to give him a major push, arranging a hectic promotional schedule to ensure everyone heard about the next big thing.

What Columbia hadn’t banked on however, was Terence’s gargantuan ego and outspoken views.

Blurring the lines between ambition and arrogance, he gave a string of press interviews in which he boasted about his sexual conquests, proclaimed himself “a genius”, described his album as “better than Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” and “the most brilliant debut album by any artist this decade”, immediately establishing himself as a divisive character.

On the one hand, there were those who were repelled by his bravado, while others lauded his refreshing no-BS demeanour.

Terence later clarified his intentions in his first interview with Rolling Stone magazine. “The simple truth is I had to do my best to ensure that my album was going to win massive attention,” he said. “I had to make sure that would happen, by hook or by crook.

“As a former journalism student, I have some idea of what makes good copy and what doesn’t. I knew that when I boasted that The Hardline… was the best debut album by a male solo act in this century that the reporter would be sure to quote that. Jesus Christ, can you not see that that was a statement dying to be put into headlines?”

Proving the adage that there was no such thing as bad press, the attention and notoriety his comments earned him initially worked in his favour when Introducing The Hardline According To Terence Trent D’Arby was released the following July.

The album sold one million copies worldwide in its first three days on sale and topped the album charts around the world.

Over the course of the following year, it went on to spend nine (non-consecutive) weeks at No.1 in the UK, returning to the top spot each time he released a single from it.

Wishing Well, Dance Little Sister and Sign Your Name all became Top 20 hits and earned him Brits and Grammys (he won Best Male R&B Vocal in 1989 after losing to Jody Watley for Best New Artist the previous year).

Aside from being a chart mainstay, he was also lauded as an electrifying live performer.

As well as his own songs, he regularly paid homage to his idols in concert and in TV performances, performing Sam Cooke’s Wonderful World, The Rolling Stones’ Under My Thumb and Smokey Robinson’s Who’s Loving You.

Martyn Ware told the Red Bull Music Academy: “He performed live and could do everything. Every move you’d ever seen Prince do, every move you’ve ever seen the original soul artists do, even James Brown, he could dance like that. At that point he was completely straight, didn’t take any drugs, didn’t drink, he looked like a god.”

So where did it go wrong? Despite Terence’s undeniable talent and success, his grandiose statements and outlandish behaviour were to be to his downfall. As he arrived in the US to launch his career in his abandoned homeland in 1988, he found his reputation preceded him.

Influential magazines such as Rolling Stone, Spin, People and Village Voice all ran profiles taking him to task for his arrogance.

The biggest music magazine in the world, Rolling Stone was incensed when Terence had the audacity to only agree to an interview if he was given the cover. They ran the cover with the tagline, “A legend in his own mind”.

Although Terence defended himself by reiterating his earlier claims he was merely playing the media game and his statements were intended to attract attention to his work, his spoken words essentially overshadowed those he sang with such passion and eloquence.

His decision to take complete artistic control of his subsequent music was a brave move which backfired spectacularly from a commercial perspective.

He never came close to replicating the success of Introducing The Hardline According To Terence Trent D’Arby and “killed off” Terence Trent D’Arby to assume the identity of Sananda Maitreya in 2001, the name by which he still releases music independently today.

With Terence’s chart rivals Jackson, George and Prince all tragically gone now, a re-introduction to Terence Trent D’Arby would be more than welcome.

Introducing The Hardline According To Terence Trent D’Arby – the songs

If You All Get To Heaven

One of the album’s most dramatic songs, If You All Get To Heaven sees Terence sing from the standpoint of a sinner bemoaning the war and destruction of the world around him. Covering religion, politics, war and psychedelia, the song sees Terence proving himself as an accomplished, well-read lyricist with lines such as: “Young men must die to keep the old ones alive and to prove they’re studs once again”. The song’s temperament is intensified by the juxtaposition of Terence’s boyish falsetto of the verses against the dark, tribal chant of the chorus (featuring the unmistakable vocals of Heaven 17’s Glenn Gregory).

If You Let Me Stay

Here’s Terence in remorseful mode, imploring his lover to give him another chance after he hadn’t treat her as well as he should have. An infectious slice of retro soul evoking the classic sound of Philadelphia and vocal harmony groups such as the Temptations and Four Tops, If You Let Me Stay is Terence promising to change and right his wrongs before, on the song’s bridge, realising he’s fighting a losing battle, and giving up. “Your pretensions aim for gullible fools and who needs you anyway?” he sings, before prophesying his lover will regret not taking him back. He may have been right, as the song was his debut hit, establishing him as one of the 80s brightest new stars.

Wishing Well

A sparse beat inspired by David Bowie’s Let’s Dance is the driving force of Wishing Well on which Terence dances the blues, adopting a deep, seductive growl to deliver lyrics which he described as a “tone poem”, singing of butterfly tears and crocodile cheers. The song’s simplistic sonic tone is also evocative of Prince’s When Doves Cry, with just a beat and a voice delivering the verse before a simple musical flourish is added to the chorus. As well as reaching the Top 10 in the UK, Wishing Well was Terence’s major breakthrough in the United States reaching No.1.

I’ll Never Turn My Back On You (Father’s Words)

A song of unconditional love and support, I’ll Never Turn My Back On You… tells of a man who has made mistakes and let his pride stop him seeking help or guidance. The semi-autobiographical lyrics are a father’s testament to his son that no matter what, he will be there for him, despite their differences and conflicts. Musically, the song pays homage to one of Terence’s musical father figures, Stevie Wonder, with a soulful, playful reggae bassline reminiscent of Master Blaster (Jammin’).

Dance Little Sister

While I’ll Never Turn My Back On You… had been about being afraid to ask for help, Dance Little Sister was a switch in roles and saw the song’s narrator in the position of offering guidance, begging the troubled female in question not to give up. “Say now, share the weight and lay your cross down/ And let the long reaching arm of hope bring you around,” he sings. One of the funkiest, most upbeat songs on the album, its breezy dance beat conceals the song’s serious message.

Seven More Days

In the grand tradition of the legendary bluesmen that had inspired him, Terence used his songwriting as an outlet for storytelling, and Seven More Days is one of the most illustrious, with the artist seeming to be singing from the viewpoint of a prisoner yearning to be reunited with his love. “Grown men wither and they dry away, their lives compromised/ I’ve gotta hold on, struggle through another day/ to see the fire in my baby’s eyes,” he sings, claiming that: “society’s debts have been more than paid” and “the walls that divide us will come tumbling down”. Comparisons to Jericho are representative of the religious imagery that permeates the album.

Let’s Go Forward

A straightforward song about love over materialism, Let’s Go Forward is the moment on the album which sounds most like the glossy, polished soul of Luther Vandross and Anita Baker which was popular at the time, though Terence’s falsetto and the gentle shuffling rhythm are nods to Marvin Gaye’s Sexual Healing.

Rain

One of the album’s catchiest melodies, it is little wonder that Rain was originally planned to be the fifth single from the record, but was dropped at the 11th hour and relegated to promo single status instead (though it was a single in Holland). The song deals with the subject of history and legacy. As with many of the songs on the album, Rain manages to seamlessly incorporate a number of different styles within the song.

Sign Your Name

Terence’s biggest hit single behind Wishing Well, Sign Your Name is his classic love song. Terence claims to have written the track after waking from a dream in which he’d watched Sade perform. A simple drum machine, synths and lush string arrangement envelope Terence’s sensual vocal in which he pledges his devotion stating: “I’d rather be in hell with you baby/ than in cool heaven”. The song was a Top 10 hit for him around the world and was later covered by Sheryl Crow and Justin Timberlake in 2010.

As Yet Untitled

An impassioned, devastating song about the political and social situation in South Africa, As Yet Untitled was inspired by the plight of Nelson Mandela. Sung entirely a capella so as to emphasise the message of the song, Terence’s performance of the track at the Nelson Mandela: An International Tribute for a Free South Africa concert at Wembley Stadium in 1990 was one of the day’s highlights. The line: “When I return, I’ll be a stronger man” was sampled by Shut Up & Dance for their seminal dance track Derek Went Mad in 1990.

Who’s Loving You

Having been raised on gospel music by his Reverend father and singer mother, the first music that Terence discovered and loved of his own was the Jackson Five. Their cover of Smokey Robinson’s Who’s Loving You was one of their most notable recordings, and Terence included his version on the album as a nod to his own musical awakenings. Another stellar vocal performance from the singer, too.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.