Thompson Twins albums

We look back on the albums of Thompson Twins and their frontman Tom Bailey…

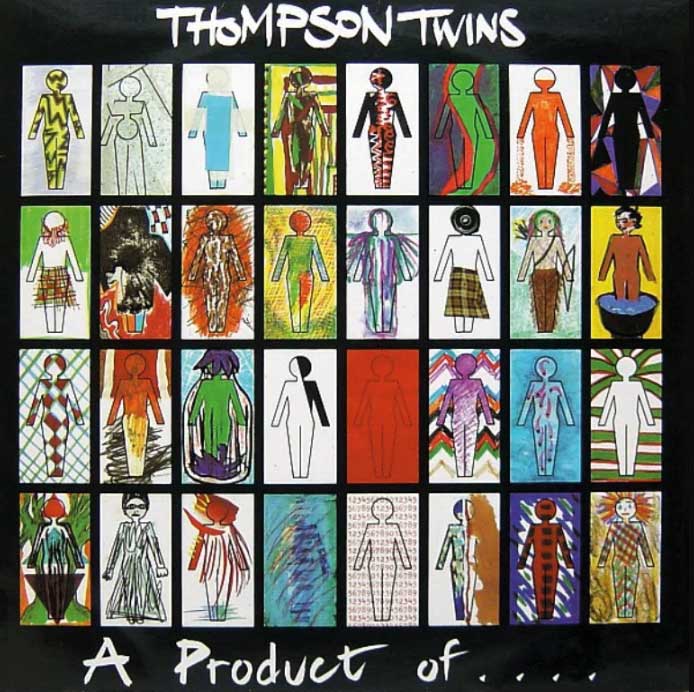

A Product Of… (Participation), 1981

Not Classic Pop’s words, but the opening sentences to the band’s first feature in The Face, published mere weeks before the release of their debut album.

Even then it was necessary to explain the story behind their ever-changing line-up, and those raised on the hits that followed – their opening UK Top 40 strike, 1983’s Love On Your Side, was the first of 10, though they saw no more after 1985 – normally recall them as a trio: Tom Bailey, Alannah Currie and Joe Leeway.

The band originally formed in Yorkshire at the height of punk, but by the time they’d self-released their first single in 1980, the not-entirely-promising, Television-like Squares And Triangles, founders Tom Bailey, Pete Dodd and John Roog were squatting in Clapham and on to their third drummer, Chris Bell.

He’d prove vital to their debut album – which, incidentally, sounds as little like the Thompson Twins of Doctor Doctor fame as they looked – because rhythm is at its heart, as it had been at their appealingly chaotic early shows, where crowds were invited to join in on stage.

Indeed, according to that Face article, two audience members, Leeway and Jane Shorter, subsequently joined the band to add percussion, though others insist Leeway met Bailey because both were teachers and Shorter, significantly, also played saxophone.

Currie, meanwhile, if not officially a member, is thanked for “playing and singing”, so yes: things were always ‘fluid’. A Product Of…, however, sounds like the work of a sophisticated, well-established unit, if one still paying off an overdraft to its influences.

In hindsight, A Product Of… could at times be The Police, with The Price’s groove slickly lazy and Anything Is Good Enough indulging their muso side.

A love for West African music is also apparent on the dubiously titled Slave Trade, which pre-empts Adam And The Ants’ experiments in the same theatre, and Oumma Aularesso, which might give Paul Simon’s later Graceland a run for its money.

They share this enthusiasm with their most obvious debt, Talking Heads, whose twitchy, tense but playful artiness thrives in opener When I See You’s spiky guitars, the New Wave-y Politics, whose jerkiness somehow remains admirably rigid, and the title track, with Shorter’s sax a vital embellishment. A product of participation for sure, then, and more than the sum of its parts.

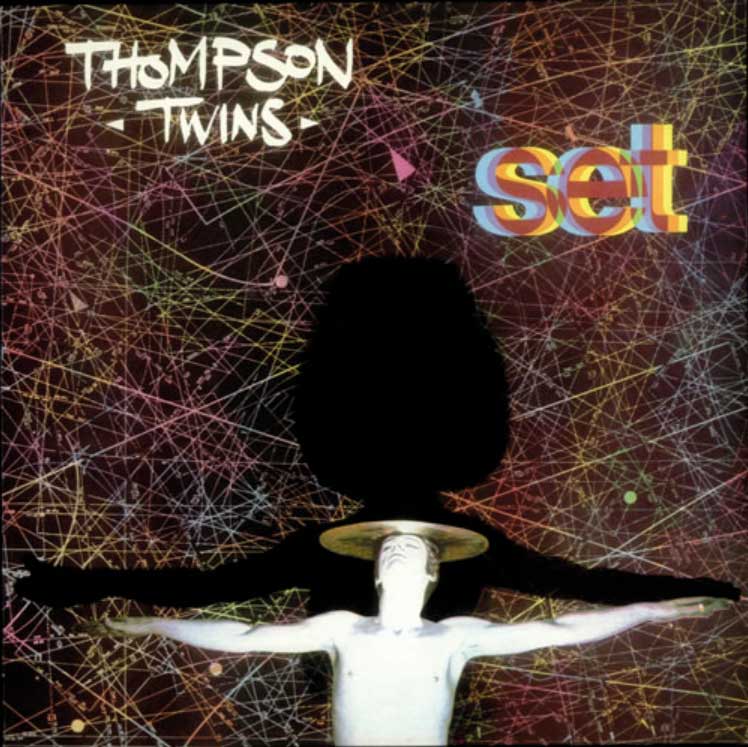

Set, 1982

Thompson Twins albums – Set

And then there were seven. With Currie now a full-time saxophonist and percussionist, and Matthew Seligman on bass – not to mention Thomas Dolby popping up on three tracks – Thompson Twins expanded their horizons on Set, aided by producer Steve Lillywhite, who helped leave their earlier squat sound behind.

They first made land in the US, where opening track In The Name Of Love – written urgently by Bailey to bulk out an album considered too short – settled at No.1 in Billboard’s Dance Chart for five weeks.

In fact, it became the title track to a US version which switched out three songs for three of A Product Of…’s, though the original performed better in the UK (No.48) than this semi-compilation did in North America.

The song, which combined familiar Talking Heads moves with a more recognisable Thompson Twins style, deserved its success, but so did the rattling, restless Living In Europe, which fared less well, perhaps thanks to bursts of PiL-like guitars.

Bouncing, too, paired a similarly high energy with a noisier, Teardrop Explodes jollity, and Crazy Dog was strident, even vaguely psychotic.

As for Tok Tok and Runaway, whose reggae stewed somewhere between The Police and The Specials, these confirmed they’d not left behind their African inclinations.

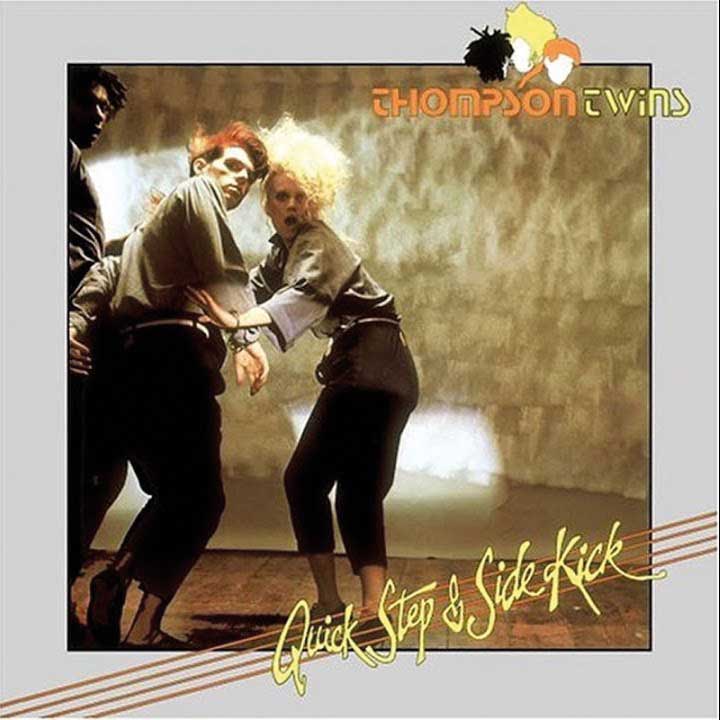

Quick Step & Side Kick, 1983

All change, all change. The Twins’ third album found them reinvented, with Bailey having – perhaps ruthlessly – split the band, only to reform it with Currie and Leeway.

Possibly such economies allowed them to head for the Bahamas’ Compass Studios, where they teamed up with producer Alex Sadkin, who’d been working alongside Chris Blackwell on recent Grace Jones and Joe Cocker releases.

Their marketing, meanwhile, was now adorned with a distinctive, cartoonish, three-headed logo designed by Andie Airfix, who also provided, among other notable work, Def Leppard’s Pyromania, Hysteria and Adrenalize covers.

Rejecting guitars almost entirely, Sidekicks – as Americans knew it – benefitted from the now absent Seligman’s inadvertently persistent influence, since he’d originally been hired to free Bailey from bass duties so he could concentrate on keyboards.

With songwriting shared, Quick Step… focused on synthesizers and dance-pop, earning a cult following in the US which in turn helped it reach No.34, to be filed alongside other Second British Invasion acts like Soft Cell, The Human League and Duran Duran.

Though first single Lies nearly repeated the American success of In The Name Of Love – which featured on 1984’s Ghostbusters soundtrack – its slightly clumsily Eastern-influenced charms eluded Brits.

However, the album’s impact was greater in the UK, thanks to the success of Love On Your Side in early 1983, which made No.9 and opened the LP with its unforgettable, niggling riff.

Talking Heads’ anxiety was still in the mix, but now soothed by polished production and celebrated by horny synths, while We Are Detective – which peaked higher, keeping the album afloat post-release – balanced Currie’s deadpan spoken words and Bailey’s mischievous Terry Hall vocals with a terrace-chant chorus.

Watching may have been a less successful single, but the album version still boasted Grace Jones’ spooky backing vocals, while If You Were Here and Kamikaze conjured up moods which might not have entirely alienated David Sylvian.

True, Love Lies Bleeding may sound primitive, even ungainly, and Judy Do derivative, but on Quick Step… the Twins found their stride, earning a British platinum album in the process.

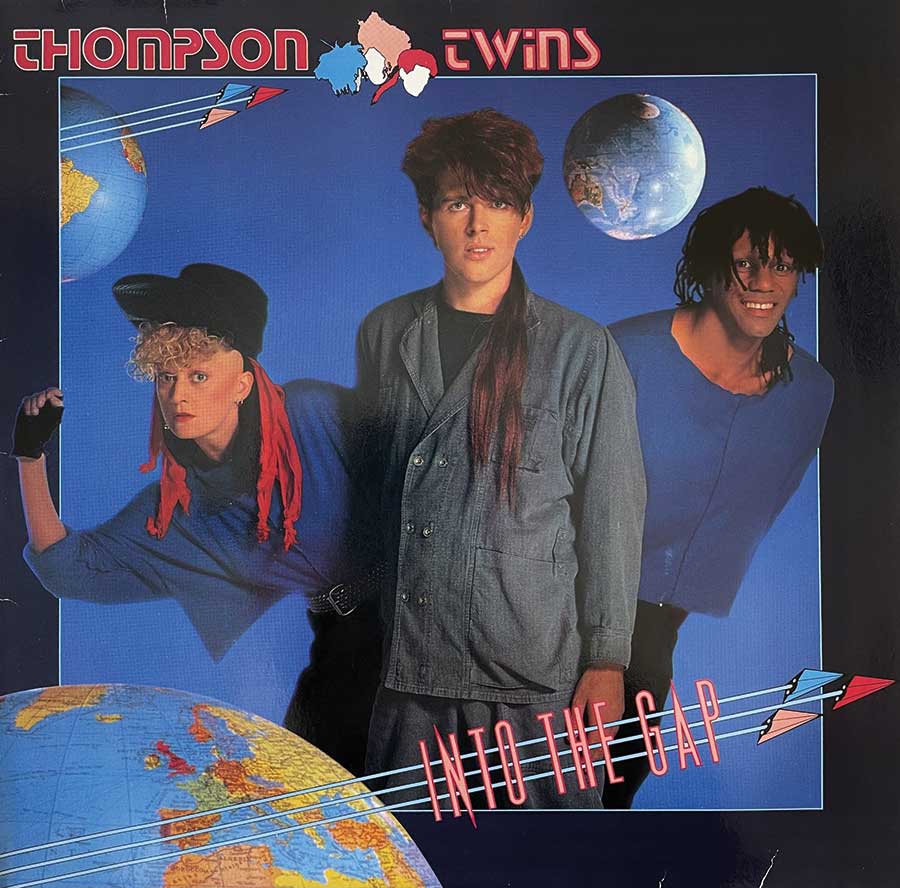

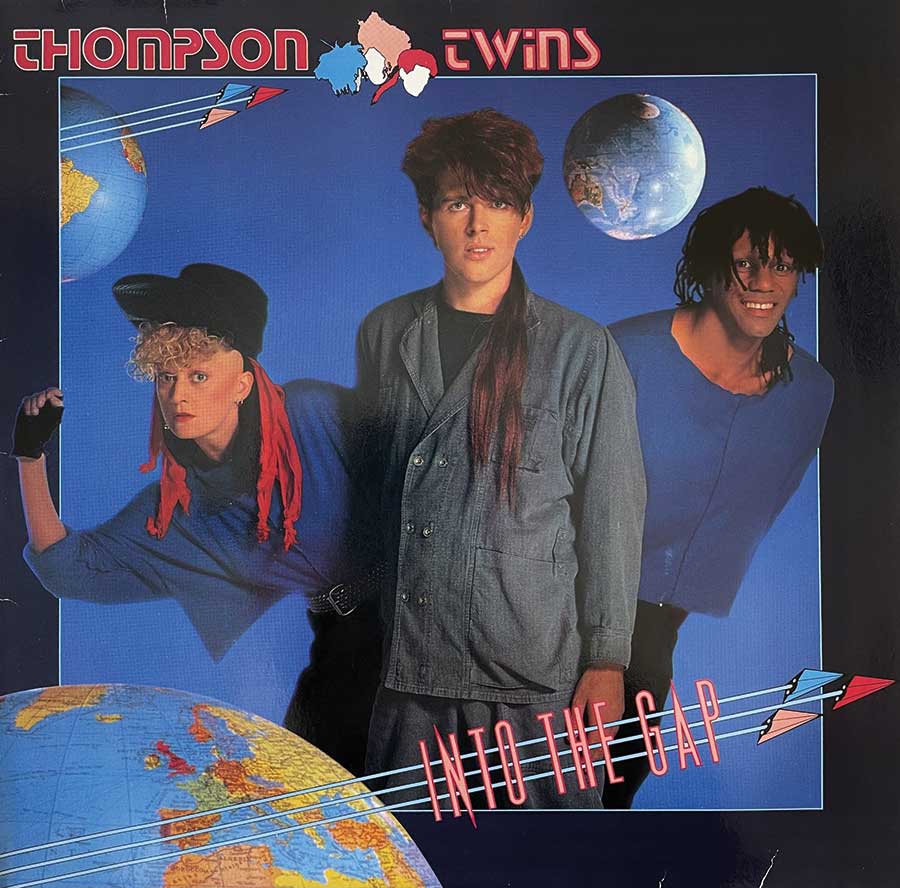

Into The Gap, 1984

Thompson Twins albums – Into The Gap

Familiarity breeds contempt, some say, and that may partially explain the sniffy response the Twins’ fourth album sometimes provokes.

Even Smash Hits complained about its “plodding tunes sung in a whiney voice”, while NME called it “1984’s most instantly kitsch mass program of monosodium glutamation of the brain”.

That they’d abandoned their unruly roots may have alienated early fans, and that their hair was deemed “surely the most hideous in the history of Western popular music” by the likes of Creem might not have helped.

If familiarity does indeed breed content, and that was true of their growing army of fans, the trio had every reason to be pleased with themselves after Into The Gap topped the UK charts and reached No.10 in the US.

Recorded again in Nassau with Sadkin – and with Bailey officially a co-producer – it arguably foreshadows OMD’s Junk Culture, released a few months later, epitomising an 80s synth-pop style that was only forsaken once indie music gained a once-unthinkable foothold.

Admittedly, some of their synth settings are a little dated to the modern ear, but this nonetheless represents the definitive Thompson Twins sound, and to the less condescending, Into The Gap‘s appeal is far greater than mere nostalgia.

For starters, despite silver-status single You Take Me Up’s gimmicky harmonica and melodica – which are anyway offset by lyrics addressing industrial labour – it’s often mysterious, with former African fancies replaced by subtle Eastern flavours on Top 3 hit Doctor! Doctor! and Sister Of Mercy.

The Gap, too, leaned eastwards, adding tablas and snake-charmer synths, but Day After Day’s two-note riff betrayed Talking Heads’ influence again while adding a little Bowie funk, and No Peace For The Wicked’s malevolence was masked by the kind of lithe groove Duran Duran’s Notorious would exploit in 1986.

Storm On The Sea and Who Can Stop The Rain provided an unexpectedly melancholic close, but it’s the irresistible Hold Me Now, a UK and US Top 5 hit, which remains best remembered for helping close the gap between their squat roots and international stardom.

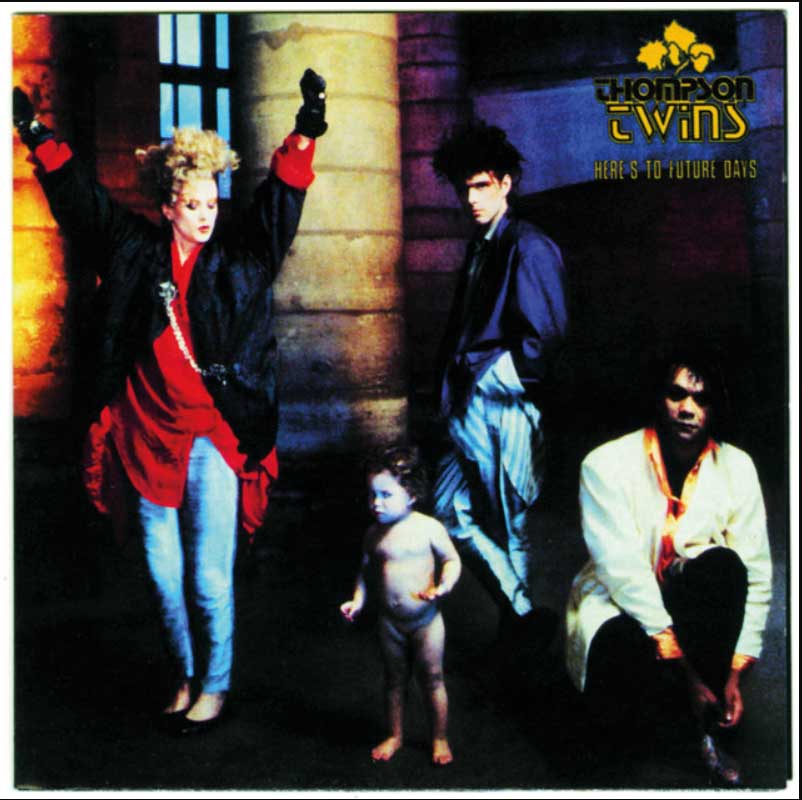

Here’s To Future Days, 1985

From the outside, with Into The Gap certified double platinum in the UK and a million-seller in the US, not to mention Alex Sadkin back on board to co-produce their new album, the Twins’ future now looked especially bright.

They returned in late 1984 with Lay Your Hands On Me, delivering healthy chart positions in the US and UK – their key markets – and by summer 1985 they and Madonna were guesting during each other’s performances at Live Aid’s Philadelphia leg, confirming their starry stature.

That single, however, was a somewhat anaemic re-run of songs like Hold Me Now, and, despite its religious themes, its gospel choirs were an ostentatious, excessive touch. (In 2014, Bailey told Yahoo Music firmly, “I’m not going to be singing it in concert.”) Behind the scenes, too, there’d been struggles.

Sadkin had been let go early in 1985, with Bailey taking over, and having immersed himself in the immeasurable possibilities of the era’s burgeoning studio technology – and with new single, Roll Over, already manufactured and the album nearly ready – he’d collapsed of exhaustion in the spring. Plans were put on ice.

Recuperating in the Bahamas – as you do – Bailey and the band decided to overhaul the record and roped in Nile Rodgers, who’d also join them and Madonna at Live Aid.

Listening to the cover of The Beatles’ Revolution they cobbled together for that show, one might have foreseen trouble ahead: like the studio version, it was bloated and unimaginative, and the album largely followed this pattern.

That they needed two 24-track mixing desks to accommodate the inordinate amount of material they’d accumulated is no coincidence.

King For A Day, for instance, was catchy but gauche, and Don’t Mess With Doctor Dream illustrated their needlessly abundant obsession with studio technology, employing vocal samples in a manner boldly reminiscent of Yello.

Future Days, meanwhile, was tiresome, You Killed The Clown was a sappy ballad, Tokyo was basically patronising, and the best one could say of Emperor’s Clothes (Part 1) was that Part 2 never turned up. Sadly, Here’s To Future Days turned out merely a pale imitation of former glory days.

Close To The Bone, 1987

Thompson Twins albums – Close To The Bone

“The Thompson Twins were never two,” The Face had written in 1981, but here they were half a dozen years later with just Bailey and Currie’s faces on the cover of their sixth album.

Leeway had quit, by all accounts amicably, to settle in L.A., and though this shouldn’t have affected the songs – his key roles had been lighting and set design for shows – Close To The Bone sounded like they’d lost their way.

To be fair, they had lost their way a little, having taken time off in Ireland, where they’d now settled, for personal reasons, not least the fact Currie had suffered a miscarriage the same day that her mother passed away.

This inspired the most personal song, Long Goodbye, with its poignant theme – “I’ve seen my future die, my whole past as well” – but though such candour might have explained the record’s title, it was largely absent elsewhere, and those lines might worryingly soon describe the band’s status, too. The album more or less bombed.

This, perhaps, wasn’t surprising. Although they’d not been strictly unconventional for a while, now they were loosely conventional, opening with Follow Your Heart’s tired transatlantic sentiments – “Don’t let no-one else do your livin’ for you” – which set the tone for a record of bland, vaguely funky dance-pop.

Get That Love, Still Waters and Savage Moon occupied territory currently being exploited with more vigour by Curiosity Killed The Cat, and Twentieth Century sounded most like The Kane Gang’s cover of Aretha Franklin’s Respect Yourself.

Elsewhere, too, it was barely indistinguishable from Sting’s contemporary solo material, and though never as clumsy as the famed police duo of Hergé’s Tintin adventures, from whom they’d borrowed their name, it was certainly no more resourceful.

That they’d turned in something at best unimaginatively serviceable was particularly disappointing given that Bailey had once told Rolling Stone his youthful musical awakening encompassed “odd things like very early Pink Floyd and a German group called Can”.

Big Trash, 1989

Thompson Twins albums – Big Trash

With Close To The Bone hammered by critics – for NME it was “commercial music of the most ordinary nature” – it was time for a traditional ‘out with the old, in with the new’ move, underlined by a new deal with Warner Brothers.

A bigger budget, however, instead provoked more ‘back with the even older’: Steve Lilywhite, who’d worked on Set, returned as co-producer, and Big Trash found Bailey and Currie calling upon guitars again as well as beefier rhythms.

A great improvement on its predecessor, with This Girl’s On Fire containing enough echoes of the older Twins to satisfy long-term fans, it nonetheless failed to prove distinctive.

Wild and Bombers In The Sky mixed contemporary funk-pop with mainstream rock, echoing INXS’ recent globe-conquering successes, and though Queen Of The USA was befitting of the emerging indie-dance sound championed by the likes of Jesus Jones, it nevertheless mined a similar seam.

Admittedly, the latter was boosted by spoken-word interventions from Debbie Harry, whose I Want That Man Bailey and Currie had recently co-written and whose Def, Dumb And Blonde album Bailey had co-produced.

On Rock This Boat, however, his own attempts to sound sensuous ended up half-hearted, and though Sugar Daddy provided a US dance hit, nothing here could quite revive their fortunes.

Queer, 1991

Thompson Twins albums – Queer

With Sugar Daddy having provided an invigorating sniff of the club success that In The Name Of Love had once enjoyed, and aware that after a decade in the game they might not be perceived as cutting edge, Bailey and engineer Keith Fernley began quietly providing white label 12-inches of a new project, Feedback Max, to London’s DJs.

In retrospect, it’s a shame that they didn’t pursue this strategy further. The first, Come Inside – whose keyboards and programmed rhythms predicted, among other things, Woke Up This Morning, Alabama 3’s Sopranos theme – perfectly suited the baggy era of Happy Mondays et al, yet when released under their own name, despite multiple formats and remixes, it merely grazed the UK charts.

The controversially titled LP was dropped from the UK release schedule altogether, but in the US – where the song, initially released anonymously, provided another Dance Chart hit – it came out as planned.

That said, despite follow-up singles in the pounding The Saint and anthemic Groove On, whose EMF swagger deserved to ape Come Inside’s success, neither could repeat the feat, and nor could the LP. Queer failed to chart anywhere.

It’s a shame, because, while this eighth LP can’t match their early-80s peak, it might have fared better were it not carrying a decade’s baggage.

Its emphasis on looped drum tracks and itchy percussion is particularly heavy, with both Bailey’s grunts and Currie’s distorted vocals boosting the title track’s appeal, while Shake It Down, albeit in slightly trite style, and My Funky Valentine, which added sax squawks and soulful keyboard flourishes alongside DJ scratches, also adopted a shuffling, Madchester-style beat.

The Invisible Man briefly disinterred their Eastern influences, too, nodding to the production techniques of William Orbit’s Strange Cargo project, but elsewhere things were tamer.

Strange Jane, later cannibalised for Play With Me (Jane) on the Cool World soundtrack, harked back to earlier times, if in less idiosyncratic fashion, and while Wind It Up packed a punch, its lyrics – “Wind it up, yeah, to a higher ground” – were painfully banal.

Not that it mattered: times had changed and the band had changed. Willingly or not, the Thompson Twins had outgrown their name.

The Stone, 1994

It was time for a new start. Bowing to the inevitable, Bailey and Currie decided to drop their venerable moniker and in 1992 relaunched as Babble, with engineer Keith Fernley – who’d helped craft the Feedback Max style – making up the trio.

This time they pursued the ascendant chillout sound that parts of Queer had hinted at, with Tribe, Spirit and Sunray Dub again indebted to William Orbit’s recent work and the trance-y, breezy Beautiful graced by a laid-back Q-Tee rap and perfect for an Ibizan beach bar.

There were hints, too, of Primal Scream’s Screamadelica in You Kill Me, while the title track leaned on mystical influences collected during a trip to India, with extensive use of tablas and Bailey’s melody mantra-like.

On Space they utilised a slowed down beat to add menace to snarled, mid-Atlantic vocals and, on the psychedelic Drive, for which Currie’s unusually atonal voice seemed to have been beamed in from space, Bailey – who’d once warned “Don’t mess with Doctor Dream” – even sounded stoned.

Ether, 1996

Though Bailey and Currie moved to New Zealand in 1994, Ether suggested little had changed otherwise. Babble’s second album opened with the trippy The Circle, which turned once more to Eastern influences and might have been mistaken, had they delivered it to London’s DJs, for a William Orbit remix of Primal Scream.

The same could be said of Sun, a celestial slow-burner on which Bailey sang particularly like Bobby Gillespie at his most baked, and Come Down, whose lyrics definitely sounded like the Scotsman’s, too.

Predicting Bailey’s work with International Observer, meanwhile, Tower’s dub was deep, and its name prompted a rare chuckle: Tower of Babble, geddit? – and, though it was their last album together, the band offered vocal duties on the deliciously lazy Just like You to Kiwi singer Taisha Kuhtze, and on Love Has No Name to Teremoana Rapley, before bowing out with a moody instrumental, Dreamfield. If they departed without fireworks, they departed with class, kings – and queens – for more than just one day.

Science Fiction, 2018

And now they were one. In 2014, having moved to France with a new wife after divorcing Currie in 2003 – and having busied himself in between with International Observer’s dub explorations – Tom Bailey began performing Thompson Twins songs again, something he apparently enjoyed as much as audiences.

After a while, though, he told Classic Pop in 2018, “You can’t just rest on nostalgia if you want to be somehow vital to yourself.”

Though Science Fiction might not have invigorated everyone, it was far from the “denial of the march of time” that The Times described, and anyone who welcomed Tears For Fears’ comeback in 2022 – and who enjoys Beatles-inflected tunes, evident in Ship Of Fools and Bring Back Yesterday – will find plenty to admire.

There were pleasant reminders of the past, not least in the title track’s squidgy synths as well as Bailey’s vocals, but for those who’d grown up with TT’s work, it seemed like a more logical step than anything since… Future Days.

Bailey also appeared to be enjoying himself, with If You Need Someone upbeat and What Kind Of World given a Caribbean twist, while if Blue was more dispirited, it was also heartfelt.

It’s been a long journey from that 70s Clapham squat to Science Fiction four decades later, but Bailey’s clearly not ready to settle.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.