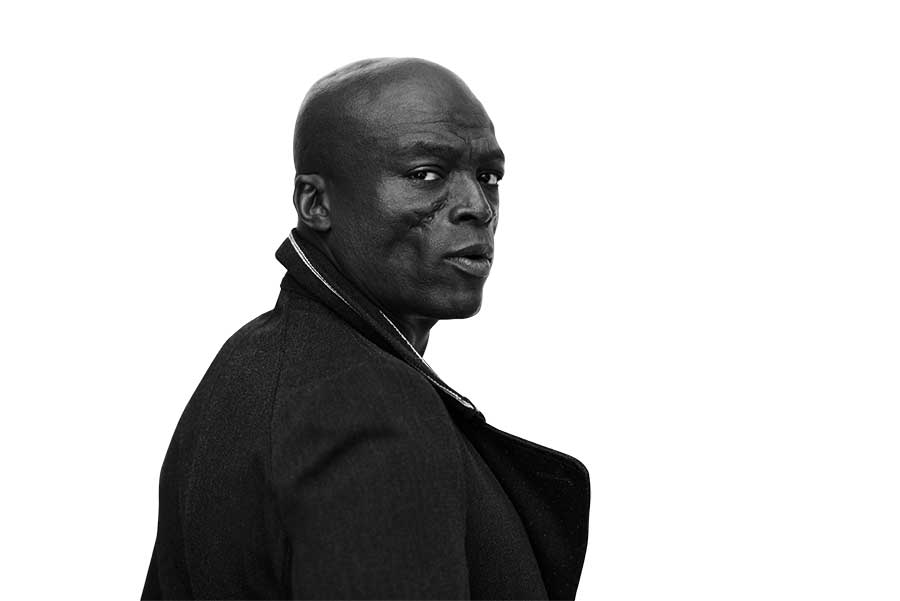

A beautiful singer with the looks to match, Seal always seemed destined for stardom. But a new reissue of his self-titled debut album is time to remember that stardom once seemed light years away for one of the finest vocalists Britain has produced. In a rare interview, Seal recalls how the stage used to terrify him, while Trevor Horn reveals their unlikely bonding influences. “It’s been a hell of a run,” as Seal tells Classic Pop…

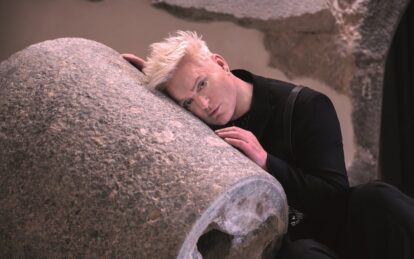

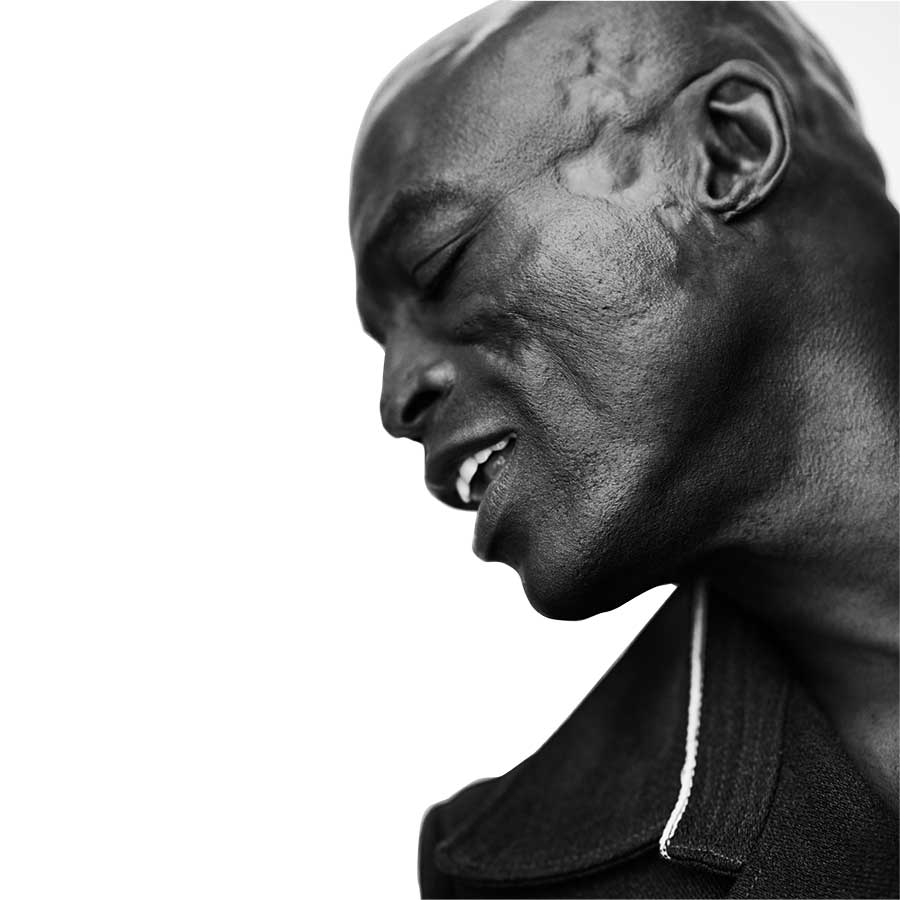

“Seal is a huge presence. The first time I met him, he had Cuban heel boots on, when he’s 6ft 5ins anyway.” So says Trevor Horn of his initial encounter with Sealhenry Samuel at the producer’s famed London recording studio, Sarm West.

That Seal sought to make himself even bigger than he was already is appropriate for a singer whose music has always been more grandiose and replete with memorable moments than such a classy vocalist needed to get by.

Where lesser talents seek to show off with vocal gymnastics, Seal knows that the song is the star.

Still, Seal’s longtime producer is right: Seal is a huge presence. Over Zoom from his home studio in L.A., the singer is relaxed for someone who rarely talks to the British press.

He’s unguarded, funny and likes a dramatic gesture into his laptop camera. He’s every bit as Seal as you’d hope, aware of his role in music.

“In people’s eyes, I’m a singer,” he notes reasonably. “Nobody wants to hear my political views. If people listen to Seal, it’s because they want relief. They don’t want me banging on about whatever.

“Therefore, my job is really simple: come up with good songs. Hopefully one or two great ones. It’s really that straightforward. It’s not like we’re performing open-heart surgery or saving lives.”

Seal has provided relief and a chance to shimmy ever since Killer with Adamski crashed to No.1 in 1990. An early example of a featured vocalist, the unknown Seal was an instant star.

As Trevor explains: “You can tell when the public is interested in someone. Buying a single, you’re just interested in the record itself. Buying an album? You have to be interested in the artist to buy their album, and I could tell the public were interested in Seal.”

- Read more: The birth of synth-pop

For all his obvious charisma, Seal was 27 when Killer got the public’s attention. In pop years, the Londoner was middle-aged to be introduced to the nation. Frankly, Seal, what kept you?

“That’s what I used to think,” he laughs. “Finding your voice, that’s the path of every artist. Before Killer, I wrote a bunch of songs I thought were great. On reflection, they were shite.”

Like a musical Doctor Who, Seal had tried a bunch of incarnations – most notably funk band Push – before finding his first niche in rave.

“I thought it was clear where I was going,” he admits. “But, when people came to see me play, they said the same thing: ‘He’s got an interesting voice, but what is he? If he’s rock, how come he’s black? Why isn’t he doing R&B or reggae?’ They weren’t interested.

“I thought they were all deaf, and my attitude was: ‘What’s wrong with you?’ The industry just didn’t know how to market me. Then someone gave me a cassette, and one play of that made me go: ‘Ohhhh! Now I see why it’s not happening.’”

The friend’s cassette featured Joni Mitchell, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix and Crosby, Stills & Nash. “I didn’t write a lick of music for a year, so I could soak up everything by these incredible musicians,” Seal reflects.

“I eventually realised what all those great musicians had in common was that they played an instrument, and their instrument reflected their music as much as their voice. I thought: ‘I’ve got to get an instrument.’”

A friend showed Seal how to play the A and E chords on guitar. “The first song I wrote after that year away was Crazy,” he states. “The whole song came in 20, maybe 25 minutes.

“Not only was Crazy different from anything I’d written before, it didn’t sound like anyone. I knew instantly: ‘I’ve got one!’ For the first time, I sounded like me.”

Such a Hollywood moment was an important step that began in 1974, when an 11-year-old Seal first sang in public, performing Johnny Nash’s classic I Can See Clearly Now on a PTA day at his comprehensive in Kilburn, north London.

“I was terrible academically,” recalls Seal. “Everyone thought I’d amount to nothing and end up in debt or in prison. Even my parents didn’t see me [as I am].”

The only person who glimpsed Seal’s potential was “the cool teacher”, Mr Wren. “He was everything to me,” smiles Seal. “He wore the cool clothes, he had long hair – he was a musician who’d got a real job. Everyone else thought I’d throw my life away, but Mr Wren told me to sing that day.

“Neither my parents nor anyone at school had heard me sing. The stage was the scariest place in the world, and I just wanted to die. And I had to sing a capella. I only sang because I wanted to be like Mr Wren, and because I loved I Can See Clearly Now.

“When I sang, it was like a scene from a movie. I closed my eyes and you could hear a pin drop. The stage turned into feeling like home and I’ve never forgotten that feeling.”

If it took writing Crazy to get on the right path, the song quickly grabbed the attention of Trevor Horn’s wife, Jill Sinclair, who ran the business side of their record label, ZTT.

Horn reveals: “Jill was a big fan of Nat King Cole. She’d say she wanted to find a modern-day Nat and one day she told me she’d found him.

“Jill played me a demo of Crazy. Seal’s vocals had been put through phasers, so I couldn’t tell how good his voice was. But I liked the song, and the line: ‘We’re never going to survive, unless we get a little crazy,’ that was great.”

- Read more: Top 40 synth-pop songs

It should be noted that, when interviewed separately, Seal and Trevor are quicker to praise each other’s skills than take any credit themselves. They’re now friends more than singer/producer, each appreciating what the other does.

Trevor: “I used to bemoan how American producers generally had better singers to work with than English producers. Then I worked with Seal, and realised what it’s like to work with one of the best.

“You do whatever it takes to set the mood, then you keep out of his way and get a great vocal out of him. His voice is so good, I’d think: ‘I’ve got a lot to live up to, to get the backing right for him.”

Seal: “The art of making great records is so rare, and I never really understood what it was before working with Trevor. A great record has a beginning, middle and end: for both a song and an album.

“Trevor has an incredible ability to make great records. I hear collections of really good songs, but I don’t hear many great records now.”

Both men are perfectionists, with Horn famed for his lengthy recording sessions. He laughs when asked if there’s anything he’d change on Seal’s debut now, admitting: “I don’t think of ‘If only’ like that. It all seems equally incredibly important at the time when working on an album, when a lot of it isn’t half as important as you’d think.”

Seal’s idealistic streak is different, and means he’s often been unable to hear his old music without wincing: “I’m always critical of my own input, thinking I could have sung it better or written a better lyric.

“My heroes – Joni, Hendrix, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye – made great records and were never concerned, I never quite achieved their excellence.

“But that’s not the point, the point is what I was reaching for. So I am always going to be critical. It’s never going to be good enough.”

Seal laughs, aware of how maddening his frustrations can be. “I don’t think it’s the right way to approach music. I’d prefer to be happy and satisfied. But then, I’d also like a 737 jet.”

Admitting that he was initially nervous about the stories of “Ooh, you’ll be in the studio forever,” as he describes Trevor’s reputation, Seal moved into a flat owned by the producer and Jill opposite Sarm West to begin work on the album.

“I feel privileged to have come up at a time when there was money in the music industry,” admits Seal. “There was never a time, whether it was 2pm or 3am, when I couldn’t walk over to Sarm West with some harebrained vocal idea in my head and not be singing it within a maximum of 15 minutes.

“That was how Trevor ran the ship. It was always: ‘When I’ve got the vocal, I’ve got the record.’

“Trevor didn’t suffer fools gladly, and the engineers had it drummed into them: ‘The vocal is the one thing I can’t control, so do not mess around with it. I want a mic set up permanently, just in case.’ Trevor never put pressure on me, as he’d say: ‘I’m not worried about you. Once the track is right, I know you’ll sing it right.’”

“Wendy had already played guitar on two songs,” Trevor recalls. “Lisa hadn’t been well for those songs and I’d never met her before. Then, when she arrived for Whirlpool, I set Lisa, Wendy and Seal up in a semi-circle and it was one of those great sessions.”

Even more fortuitously, for the complex rhythms of The Beginning Seal had asked Horn to track down a Detroit-based drum programmer who’d played with Inner City. “I was wondering how to find him,” says Trevor. “I went to the toilet in Sarm and passed a guy who was muttering at the Asteroids arcade machine.

“As it was my studio, I’d become pretty good at Asteroids, so I gave the guy a tip on how to get to the next level. We got chatting – and he was the programmer Seal had asked me to find. I told him: ‘There’s some work going in the studio downstairs if you fancy it.’ Just goes to show how random it can all be.”

By then, they’d become firm friends. “We both had the same sense of humour,” smiles Trevor. “We both liked old English comedians and were particularly fond of Frankie Howerd and Ken Dodd. You’ve got to get on with someone if you’re going to spend all those hours in the control room.”

Seal says of Trevor: “I still look at him as the older brother I never had, someone I can confide in. We have an unspoken communication after 30 years. We’ve seen each other at our highest and lowest.”

The singer credits Horn with instilling a good work ethic, ensuring that his music is done properly. Not that this method was always easy to grasp. Seal imitates the producer’s gentle County Durham accent: “Trevor would say: ‘I don’t have the record yet.’

“We’d be 27 versions in on Crazy or Prayer For The Dying, when I’d thought they sounded great 20 versions ago. I’d think: ‘What are you waiting for?’ But the first time I heard Crazy on the radio, I thought: ‘Ah, now I get it’.

“Crazy jumped off the radio and it sounded like it immediately belonged on the airwaves. That was the first inkling I got of what Trevor means by ‘the record’.

“Owner Of A Lonely Heart, the single made when Trevor was in Yes: if that comes on the radio, man, that’s a jewel in the crown. It doesn’t matter what song is on before or after, that song jumps off the radio and is right in your face. That’s great record-making.”

Seal cites his classic, Kiss From A Rose, as a textbook example of the pair’s attention to detail. Each of the hit’s many vocal harmonies has eight tracks, which Seal would record individually, six to nine takes for each track.

“The payoff would be when Trevor would pan those eight tracks from left to right in the studio,” beams Seal. “They’d sound beautiful. I worked with some American artists a couple of years ago, and they were shocked that that’s how I record backing vocals.

“Not just that I don’t use software, but the speed I can do it at. That’s what Trevor drummed into me. He taught me to think big and believe big – to be better.”

It’s an ethos Seal takes into writing songs, and helps explain why it’s been seven years since his last album of new material, 7. “I’ve never been one for releasing music for the sake of it,” he shrugs. “I don’t need to stay current or stay in the public consciousness.

“I make music when I have something to say. If I don’t, I’ll do something else I’m passionate about. I’ll go play tennis. “Thankfully, I have a body of work that’s representative of things I feel strongly about, that needed to be said.”

Seal might not need to stay in the spotlight, but he accepts he doesn’t return home to the UK enough. His last shows here were in 2018.

“I’m really touched you refer to England as ‘home’,” he says, with a smile that seems to be 6ft 5ins in its own right. “I very much regard England as my home. When I come back to England, it’s the one place I know where I am.

“Not geographically, but where I am in life. If I’m talking to a cab driver, I know where I am with that banter. The missus and I have been talking a lot about spending more time coming back closer to… if not England, at least Europe.”

Seal’s daughter Lou is 13, while sons Henry and Johan are 17 and 16. “The kids are grown up now,” he says of his children with ex-wife Heidi Klum.

- Read more: The story of 1983 in music

“My stepdaughter…” He quickly corrects himself on how he refers to his new wife’s daughter. “Our daughter Imogen goes to a French school, which has annexes all over the world. Moving back wouldn’t be that difficult a transition.

“The older I get, the more I think about coming back. That affects the music I make, as it affects who you come into contact with. And I will be touring England in the very near future.”

Not only does England still feel like home, so does the stage. “The stage doesn’t feel like my only home,” he points out. “Home is where the heart is, and my heart is with my family: my beautiful spouse, my dogs.

“There’s a feeling of happiness and contentment. The stage does still feel like home, but only because right here, where I’m talking to you now, feels like home.”

Of course, that contentment doesn’t quite spread to being wholly at peace with his back catalogue. While Seal has just been reissued as a 4CD and 2LP boxset featuring remixes, rarities and a compelling live show from Dublin, the singer is unfussed about the prospect of additional future reissues… bar one.

“I’d like to remaster Human Being,” he frets, referring to 1998’s unfairly neglected third album, which disjointed Seal’s career when it only reached No.44 in the UK.

It’s an overlooked Balearic gem in both Seal and Trevor’s careers. “It got compressed twice: heavily in the experimental mix, and heavily again in the cut,” ponders Seal of the album’s sound. “But it’s a record that I’m very proud of.

“During the course of your career, you’ve got to make an album like Human Being: completely uncompromised, made for you and you alone. It was a difficult record to make, but probably my favourite time on reflection. So, that’s one I’d like to have remastered. The others? Nah.”

Horn names 2003’s subsequent IV as his favourite Seal album – “It makes me remember happy personal things and is one I had in the car for a while,” he notes – but is slightly wary of producing another with his friend.

Although Trevor’s planning to play bass in Seal’s band on a US tour of the first two albums in full, the prospect of producing a new LP is slightly daunting at 73: “I’d make another album with Seal if it was the right record and the right moment. But I’m getting on a bit, and the hours I put in when producing? I’m not sure I want to do that now.”

Trevor is similarly pragmatic about why he’s produced five of Seal’s albums, smiling: “Hugh Grant was once asked if he gets the pick of any film role he wants. His reply was: ‘It’s surprising how hard it is to find roles for what I do, especially as you get older.’

“What you do works with some people – and it just works for Seal and me. I like Seal’s voice so much, I can defer to it. We’ll change tracks around, but I know he’ll always sound great. Finding people you work with can be hard, so why not keep going with Seal?”

If Trevor isn’t ready to commit to a full album, Seal would need to find another producer to fit with. He’s starting to assemble the songs, at least.

At the start of our interview, Seal excitedly plays the demo of a new track, A Little Lie, that he has written with Chris Bruce, co-writer of State Of Grace from Human Being.

Even over our respective laptop screens, A Little Lie sounds a mighty catchy beast, unusually guitar-heavy. “This is going to be good when it’s finished,” enthuses Seal. “It’s probably an opener.”

With new songs and new love, Seal seems in a good place. He agrees. “Considering how difficult it was in the early part of my life, I’ve done well,” he muses. “Wherever it is we go to in the ether, I’ll look back with zero regrets.

“I’m not just talking career-wise, but everything: kids, divorce, loves lost and found, how active I am physically and emotionally – all of that.

“At 59, I find myself in a position where, if I got hit by a bus tomorrow, I’d think: ‘You could probably have done one or two things better. But bloody hell, what a run!’”

It feels like Seal still has plenty to say. And if not, he plays a mean game of tennis.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.