Things that dreams are made of: The birth of synth-pop

By Classic Pop | October 20, 2022

Kraftwerk may have gotten there first, but it was the British groups of the late 70s and early 80s who picked up the electronic baton and ran with it. The likes of Soft Cell, Depeche Mode, Yazoo and OMD created a sound and defined an era. Classic Pop speaks to Gary Numan and Martyn Ware about this pioneering period for UK pop… By Paul Lester

There are arguments about who was first: was it The Human League? Was it Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark? Was it Gary Numan? But there’s no denying that the late-70s and early-80s was a golden age for British electronic pop music, or synth-pop.

Alongside The Human League and spin-off outfit Heaven 17, OMD and Gary Numan, were acts such as Associates, Japan, Visage, Simple Minds, Soft Cell as well as the likes of Fad Gadget, Depeche Mode, Yazoo, Eurythmics, A Flock Of Seagulls and Talk Talk.

There were also new pop groups (including ABC and Scritti Politti) and the New Romantics (Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet), all using cutting-edge technology: ARP Odyssey, Roland Juno 106, Yamaha CS-80, Korg MS-20, Oberheim OB-X, Fairlight CMI, Roland Jupiter-8, Minimoog, Sequential Circuits Prophet-5 and E-mu Emulator.

Groups doing similar work in Europe and beyond – from Belgium’s Telex, Germany’s DAF and Switzerland’s Yello to Japan’s Yellow Magic Orchestra and America’s Sparks – added to the sense that synth-pop was music’s new global lingua franca.

For a while, it seemed as though, to paraphrase Buggles, electronic pop killed the rock’n’roll star.

There is some debate about where electronic pop originated, but most agree that Kraftwerk were seminal.

- Read more: Top 40 synth-pop songs

The list of influences on Britsynth is exhaustive: from the avant-garde classical music of Stockhausen, John Cage and Steve Reich, to the innovations of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and the invention of the Moog and Mellotron.

The progressive rock of King Crimson and Pink Floyd, the krautrock of Can and Neu!, the drone-rock of The Velvet Underground and the early electronic experiments of White Noise, Silver Apples and United States Of America were all significant.

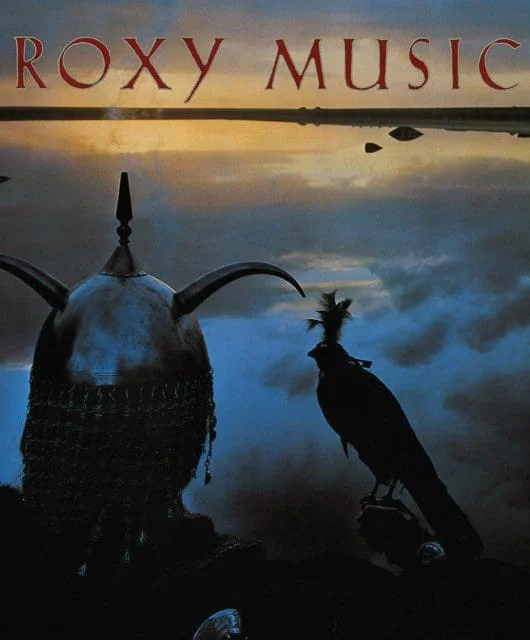

As was the soundtracks of Walter/Wendy Carlos and John Carpenter; the bubblegum beat of glam; the postmodern art rock of Roxy Music; the novelty bounce of Hot Butter’s 1972 hit Popcorn.

Also factor in the attacking sonics of Cabaret Voltaire, the forbidding synthscapes of Tomita and the motorik Eurotronica of David Bowie’s Station To Station – which brings us neatly up to 1976.

By 1977, beyond the twin landmarks of Bowie’s Low and “Heroes” (plus Iggy Pop’s attendant The Idiot/Lust For Life and Eno’s Before And After Science) and Kraftwerk’s Trans-Europe Express, synthesiser pop was being fully integrated into the various circuitries of pop (Space’s Magic Fly), assaultive New York punk (Suicide’s debut album), disco (Donna Summer/Moroder’s I Feel Love), UK new wave (Ultravox’s Hiroshima Mon Amour), even West Coast classic rock (The Beach Boys’ Love You, which was made virtually single-handedly using synths such as the Minimoog).

- Read more: The complete guide to Japan

Although they were little known at the time, the tentative bleeps and boosts of a Sheffield group appropriately called The Future, who came together in 1977, were incredibly prescient.

Sounding like the output of the Warp label from circa 1990 (and not released until 2002, when producer Richard X issued them as The Golden Hour Of The Future), the raw-sounding tracks recorded by the members – Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh, both soon to be of The Human League, plus Adi Newton of Clock DVA – in a makeshift South Yorkshire studio represent the first serious attempt to forge a new kind of British electronic pop.

“I regarded it as a training exercise – we were just feeling our way,” Martyn Ware tells Classic Pop of his tenure with The Future, speaking from London’s Tileyard Studio.

“We were quite daring, even if clearly we weren’t very commercial. The market wasn’t quite ready for it. Besides, we didn’t want to be pop stars at that point. We had limited instrumental resources, not like today with millions of virtual synths. We were playfully avant-garde.”

Ware grew up on a diet of Bolan, Bowie, krautrock, prog, New York rock, proto-electronica and disco – “a real Bush Tucker Trial of mixed ingredients,” he laughs.

“We were pretending to be a band at that point, but never believed it could come true. We were just absorbing as many influences as we could, more interested in music as a credible hobby, not a career.”

Sound of the underground

Forty years ago, Ware’s competitive streak must have kicked in, because around the same time (1978) as the first post-punk DIY-synth releases by the likes of Daniel Miller aka The Normal (T.V.O.D./Warm Leatherette), Robert Rental (Paralysis) and Thomas Leer (Private Plane) – beneficiaries of the democratisation of the new technology – The Future changed their name to The Human League and issued their debut single, Being Boiled.

“We were on a mission,” Ware says, even if winning the race to issue the first British synth single was not crucial. He acknowledges the significance of fellow Sheffield proto-electronicists Cabaret Voltaire, who he describes as “our mentors and good friends, with a similar ‘fuck you’ attitude as us”.

“We weren’t looking to place ourselves in any peer cosmology. We didn’t feel competitive with anyone. In fact, we didn’t want to know what anyone else was doing.”

If 1978 was the year of the first leftfield Britsynth singles, 1979 saw those underground sounds infiltrating the mainstream for the first time: The Flying Lizards’ Money, M’s Pop Muzik, Buggles’ Video Killed The Radio Star and Gary Numan’s Are ‘Friends’ Electric? (with Tubeway Army) all reached the UK Top 5 and, in the latter two instances, No.1.

Numan’s success, in particular, was overwhelming – in 1979 alone he reached pole position in the singles and album charts twice each (with Are ‘Friends’ Electric? (with Tubeway Army) and follow-up Cars, and the attendant Replicas and The Pleasure Principle albums, both 1979) – it rankled with pop contemporaries The Human League and OMD who saw him as a Johnny-come-lately, although in truth he had been combining traditional instruments with electronics since Tubeway Army’s 1978 self-titled LP.

- Read more: The Human League – album by album

“I didn’t know they were there, really,” Numan laughs when Classic Pop enquires about his peers, over the phone from his home in Los Angeles. “I barely knew there was an electronic thing going on.”

He knew about Bowie, Eno and Kraftwerk, of course. More than anyone, he adored Ultravox and their frontman, John Foxx. “I loved the songwriting, the way they integrated electronics with more classic elements – it was a more advanced version of what I was doing,” he says.

“Even when I had success I thought Ultravox were better than me and I still do. People said I was copying David Bowie and I kept saying: ‘No, I’m trying to copy John Foxx!’”

He somewhat contradicts his earlier statement when he admits to being aware of The Normal and OMD, who, in 1979, issued their debut single, Electricity. “When I did my first [solo] tour I called up Daniel Miller because I loved what I’d heard him do.

“But he couldn’t commit to [supporting Numan on tour] because he was setting up Mute, so instead I asked OMD. I was doing my own thing, and we had this cool electronic band supporting me. It felt like a little wave of the future. It was really quite exciting.”

Infiltrating the mainstream

If 1979 showed early glimmers of synth-pop’s commercial potential, 1980 was the transitional year when post-punk realised it, too, could pursue this new gold dream of chart success.

Arguably the two signal events in this shift from the austere grey of post-punk to the bright, bold colours of new pop were the morphing of Sheffield electro terrorists Vice Versa into ABC, and The Human League’s bisection into, well, The Human League Mk II and B.E.F./Heaven 17. Associates, Simple Minds and others would soon follow suit.

Ware fondly regards the first two League albums (1979’s Reproduction and 1980’s Travelogue) and he rightly feels a lot of their pop sensibility was already in place before the split, on tracks such as Marianne (“A fantastic piece of pop writing,” he affirms).

That, plus the fact that they had a potential pop star in their ranks in the form of Phil Oakey, made them doubly upset when they failed to beat Numan to the chart punch.

“Imagine our dismay when, straight out of the box, Gary Numan had hits with some fantastic-sounding singles, going straight in at No.1 and on to Top Of The Pops. He [Numan] nicked our synth-based vernacular a little bit.

“We were like: ‘What the fuck happened there? That should be us!’ It came as an enormous earthquake for us. Everyone else piled in after us. We felt a little bit upset.

“This ramped up the pressure considerably for The Human League to have a hit album, and those tensions behind the scenes were what caused the split, really.”

Numan was unaware of any ill feeling, although he did read something Andy McCluskey said years later, perhaps tongue-in-cheek, about how he “appeared out of nowhere and stole everyone’s glory”.

“There was a huge wave of people after me,” says Numan. “Every record label around the world was trying to sign up their own [electronic pop act]. It became a very fertile scene to be part of.

“It’s difficult to know if [synth-pop] wouldn’t have happened [without me], and I rarely make any claims for my own importance, but I do think I opened the floodgates and made it easier for people like OMD and The Human League to get listened to.”

Numan believes his success was a case of right sound/vision at the right time. “People like pop stars,” he reasons.

“I was different enough to be considered new, but conventional enough to be accessible. I used guitar, bass and drums and new technology and subject matter. ‘Friends’ was about a robot prostitute! Not exactly your average pop song.”

- Read more: Vince Clarke’s side projects

Ironically, for all Numan’s synonymity with synths, much of his music was made using non-electronic equipment. “Replicas, my second album, has more guitars than anything,” he points out.

“There are songs on that album that have no electronics at all. ‘Friends’ – the first really big song in electronic pop – has guitar all over it!

“The Pleasure Principle was the only one of my albums to not feature guitar, and that’s because I wanted to make a point to the press, who had criticised Replicas for being somehow more ‘inauthentic’ than so-called ‘proper’ music. But I love guitar! I love all instruments.”

Blockbusters go head-to-head

Ware’s approach was also to combine electronics with “real” bass and drums. He and Ian Craig Marsh were fans equally of punk (even if they found it a little, in Ware’s words, “recherché”) and disco, of European electronica and black American dance music. They wanted to be part of the ongoing electrification of funk and disco.

With Heaven 17 – the pop group part of the hit factory/corporate behemoth that was the brilliantly conceived British Electric Foundation (B.E.F.) – they ushered in 1981 via the shiny, polemical synth-funk of (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang.

Ware credits Heaven 17’s (and The Human League’s) manager, Bob Last (of Fast Records), with “triggering the idea of a company with an imaginary self-fulfilling prophecy”, with a “logo designed to look like the sort of brass plaque you see outside financial institutions in the city”.

Meanwhile, Ware, Marsh and blond crooner Glenn Gregory – actually “three working-class lads from Sheffield” – were re-imagined, on the cover of Heaven 17’s dazzling debut album Penthouse And Pavement, as businessmen doing deals.

One of the greatest compliments paid to Ware was by Last, who compared his rubbery, spacey keyboard-playing to that of Parliament-Funkadelic founder member Bernie Worrell.

- Read more: The making of Penhouse And Pavement

Also flattering was the terror induced by the deathlessly perfect rhythm programming of the LinnDrum computer, which Ware describes as sounding: “Like real drums, but doing things that a real drum couldn’t do – that made musicians feel uncomfortable, even angry; they saw it as a betrayal of their craft.”

No year before or since has been so dominated by two albums: Penthouse And Pavement and Dare, the LP made in 1981 by the remaining members of The Human League (with new recruits Joanne Catherall, Susanne Sulley, Jo Callis and Ian Burden).

A blockbusting all-synths enterprise, Dare was recorded partly at Monumental in Sheffield – the same studio where Heaven 17 recorded Penthouse And Pavement.

“It was like an arms race,” Ware remembers. “There was a lot of competitiveness. I had to concede Dare was a very, very good album.

“The fact that myself and Ian got one per cent on retail on Dare, for giving them the rights to the band’s name, softened the blow.”

Penthouse And Pavement and Dare were the landmark LPs, but it was also a classic period for synth singles: Soft Cell’s Northern Soul revamp Tainted Love, Visage’s Fade To Grey and Japan’s Quiet Life.

You can add to those, Associates’ White Car In Germany, Scritti Politti’s The “Sweetest Girl” as well as the fast-developing Depeche Mode’s Dreaming Of Me and Just Can’t Get Enough.

Also worth singling out for praise (pun intended) would be Fad Gadget’s Make Room, New Order’s Everything’s Gone Green/Procession, OMD’s classy melodicism of Joan Of Arc and Souvenir plus Thomas Leer’s Four Movements, not to mention Numan’s She’s Got Claws, the League’s seminal singles Love Action and Don’t You Want Me and Heaven 17’s I’m Your Money and Play To Win.

Showcasing the new

In 1982, a slew of albums that served as showcases for electronic pop: ABC’s The Lexicon Of Love, Simple Minds’ New Gold Dream (81-82-83-84), Associates’ Sulk, Cabaret Voltaire’s 2×45, Depeche Mode’s A Broken Frame, Duran Duran’s Rio, Spandau Ballet’s Diamond, the League’s Love And Dancing and Soft Cell’s Non Stop Ecstatic Dancing.

The trend for forward-thinking pop continued into 1983, the year of Tears For Fears, Thompson Twins, Eurythmics, Howard Jones, Blancmange and Nik Kershaw.

While maybe not quite as fiercely innovative as the first wave, these fine electronic artists acted as standard bearers of the new sound. However,1983 was also the year of The Smiths and R.E.M. – the year that rock, in a sense, regained its earlier primacy.

There were electronic pop successes to come, for ZTT’s Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Blancmange, Propaganda and Art Of Noise.

- Read more: Essential Eurythmics songs

Synth-pop enjoyed something of an Indian Summer in 1985, with notable releases by Oslo’s a-ha (Hunting High And Low), Associates (Perhaps) Scritti Politti (Cupid & Psyche 85), Prefab Sprout (the Thomas Dolby-enhanced Steve McQueen), Kate Bush (Hounds Of Love) and early singles by Erasure and Pet Shop Boys.

But really, UK synth-pop’s heyday was 1978-1982. “I’d maybe stretch it to 1983 [the year of Heaven 17’s biggest hit, Temptation], but that’s essentially how I feel,” Ware agrees.

“People say: ‘That’s convenient, because that’s when you were most successful!’ We were just lucky to have been there.”

It was a no-holds-barred time, a free-for-all. And it was largely thanks to punk, Ware contends, when “record companies had no option but to relinquish egotistical control… They spent money, creative impetus was in the hands of the artists, and you got this amazing work.”

As the 80s progressed, the labels reacquired creative control, and focus groups and market analysis took hold: he cites as an example of poor judgment the decision taken for The Human League to work with Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis.

“That wasn’t a natural fit,” argues Ware, who also experienced the dull-wittedness of record companies first-hand with Heaven 17 in the mid-80s. “It was a Jam & Lewis album, with Phil singing on it.”

The knock-on effect

Even if synth-pop in its original incarnation didn’t survive, its DNA did work its way into hip-hop, Chicago house, Detroit techno, industrial and beyond, right up to today’s EDM and chillwave.

“I swear to God I never thought – nor did many at the time – that people would still be listening to that music 35 years later, except for its curio status,” Ware exclaims.

“In 2017, we did our first sellout tour in Britain and our first ever full live dates in America, which also sold out – it’s just insane. I don’t understand it. But I’m not complaining.”

Gary Numan finds his reputation as a synth pioneer hilarious: “It wasn’t until my third album that I actually owned a synthesiser,” he reveals, laughing.

“It’s funny: after Replicas I was doing interviews with music tech magazines, but I’d only spent a matter of hours with a synth. We made Replicas in five days; I had a synth for the first three of those days, then it had to be taken away cos we couldn’t afford it!

“It was all incredibly quick and rushed and amateurish because I didn’t know how they worked; I just twiddled the dials till they made a sound I liked.

“Tech magazines would ask me what oscillator I preferred. I didn’t know what the fuck an oscillator was! I ended up with a reputation for technical genius, but I just blagged my way through.”

- Read more: Top 40 Vince Clarke songs

Nevertheless, he can see how impactful his music, and that of his peers, remains. “It even infiltrated other areas: Queen used to have signs saying ‘no synthesisers were used on this record’. ‘Synth’ was a dirty word. Then they started using keyboards.”

Ditto their classic/hard rock contemporaries: Yes, Bruce Springsteen, ZZ Top, Van Halen… Suddenly, synths were everywhere.

“It’s true,” he says. “That early stage of electronic music has had a phenomenal reach in terms of what’s spun out of it: multiple genres. I find that absolutely incredible. When I was doing that stuff at the end of the 70s and start of the 80s, I had no idea this would happen.

“The fact that this stuff has been absorbed and influenced other genres in sometimes quite dramatic ways is mind-blowing.”

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!