We Heard A Rumour… – Bananarama Interview

By Classic Pop | August 3, 2017

We heard a rumour…turns out it’s true! Bananarama are back in their original incarnation after 30 years apart. How did that happen? Classic Pop finds out…

Welcome back from suspended animation on Mars – or rather, ‘Venus’ – if you haven’t heard: Bananarama have reformed. Yes, the girl group with edge – and an entry in the Guinness Book Of Records as the all-female outfit with the most chart entries in the world – are, as Smash Hits would have it, back, back, BACK. And they’re looking fabulous, all three of them, smartly dressed in matching black, sitting in a row on a bench seat in the restaurant of a London hotel. Indisputably Bananarama-esque. That’s the most striking thing about them. In fact, it’s Classic Pop’s opening gambit: to remark on how incredibly like Bananarama they look.

“That’s because we are [Bananarama],” Siobhan Fahey states the obvious in her husky drawl. It’s partly jet-lag – she has just flown in from Los Angeles, where she lives (she also owns a place in East London) – and partly just the way she speaks. You can imagine her coolly appending a “dahlink” to her sentence, in the manner of an aristocratic German dowager from a bygone era.

“We were best mates before we started… there’s always this bond” – Fahey

Meanwhile, despite the busy, bustling scene – it’s lunchtime at one of the capital’s chic-est eateries – the diners are feigning interest in their seared salmon and quinoa. That’s because Fahey is here with Keren Woodward and Sara Dallin, making this the first time all three ’Nanas have been spied together in public for 30 years, give or take their brief reunion in 1998 for Channel 4’s Eurotrash and a 2002 performance at London club night G-A-Y.

A little nudging of one’s neighbour’s ribs is allowed – after all, it is only hours since they announced that they will be reforming for a series of gigs later this year. Already they are all over the tabloids, broadsheets and social media like a new pop rash.

They didn’t always elicit such enthusiasm. There was a time when they were regarded as girl-pop lightweights next to the likes of ABC, The Human League, Depeche Mode and Japan. Even the most foppish new romantics – Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet – got a better deal from the media.

“It was really blokey back then,” Dallin says of the music press, which took against them in her estimation because “we were reasonably attractive females singing pop” and furthermore because “we weren’t female singer-songwriters like Annie Lennox [and] they didn’t know what category to pigeonhole us in”.

As a result, “We were never held in the same high esteem as those male bands.”

“Even though,” Fahey continues, “we constantly grew and developed as writers and stayed ahead.”

“There were very few women around in those days,” Woodward considers, “and the few that were had to be extra hard bitches, so there were lots of nasty articles about us.”

10 of the best

The hits that made the girls record breakers

Really Saying Something

A cover of a Motown song originally performed by The Velvelettes, this confirmed Bananarama’s love of 60s girl group pop.

Cheers Then

Despite failing to chart, this remains one of their best, a song about the end of a friendship that became even more poignant in the wake of The Split.

Cruel Summer

The one popular with tattooed boxers: the girls remember coming out of their hotel in LA, only to find Mike Tyson singing it to them.

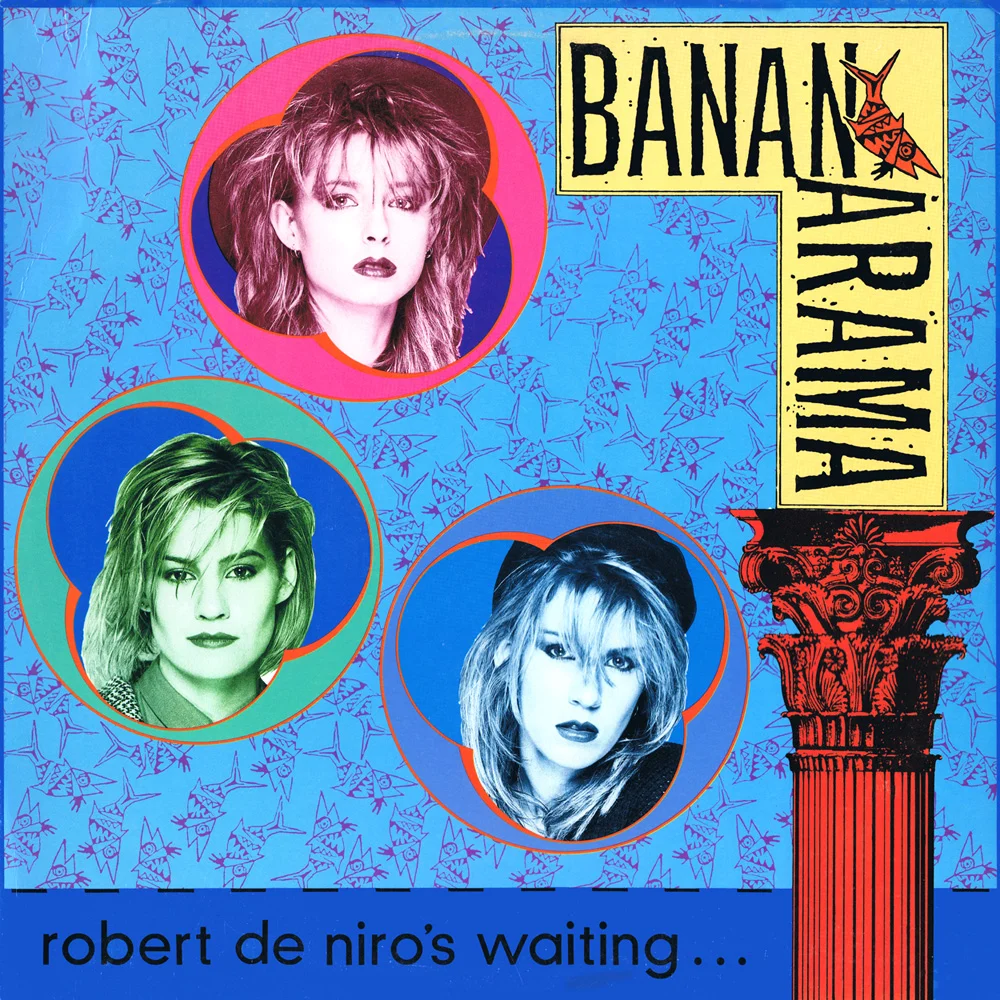

Robert De Niro’s Waiting

It’s not immediately apparent that this is a song about date rape, but as with many classic pop hits the feelgood veneer often masks hidden depths.

Young At Heart

The original version, from Deep Sea Skiving, with more of a Motown feel than the Bluebells hit.

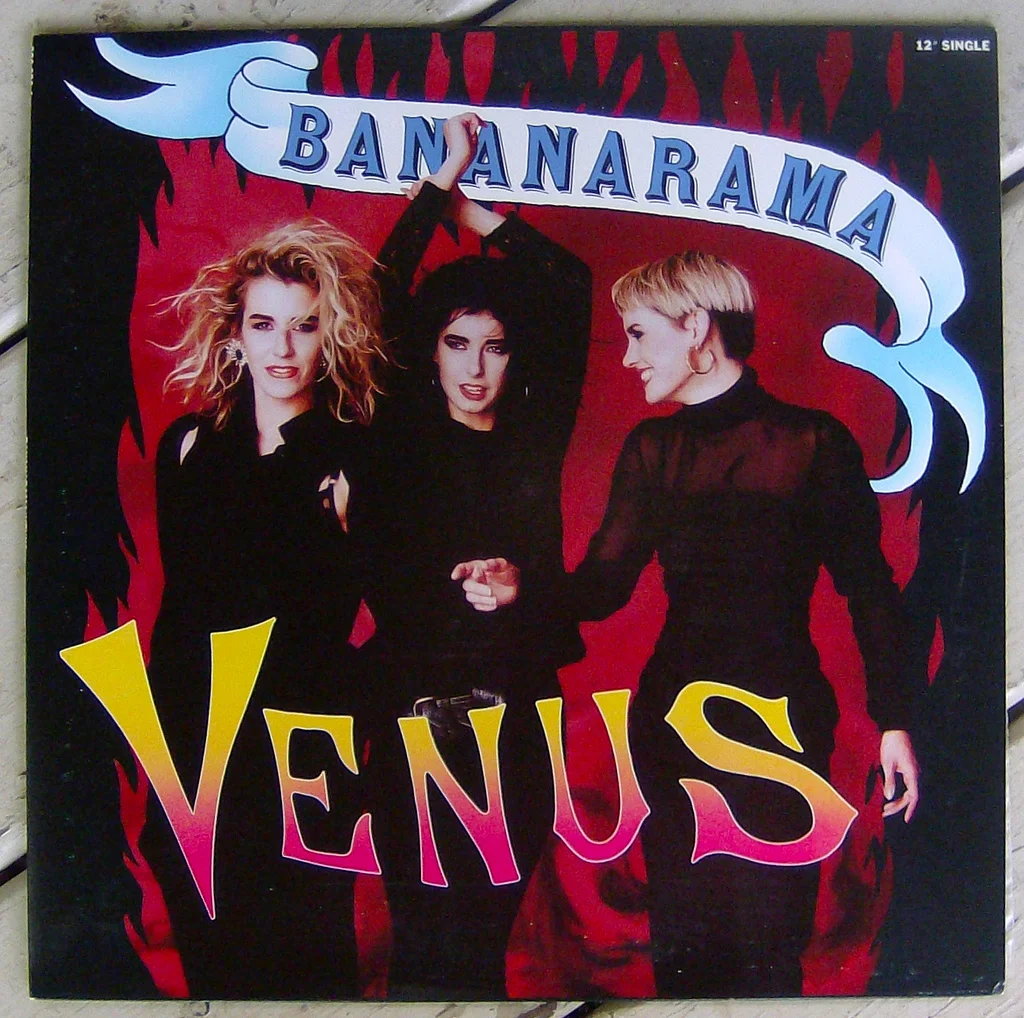

Venus

The song that ushered in Phase II of their career and reached No.1 Stateside.

I Heard A Rumour

One of Pete Waterman’s own favourites from the PWL canon, this was a classic dance-pop construction, the video an excuse to strike a pose (some have suggested Madonna wouldn’t have existed without the ‘Nanas: true story).

Love In The First Degree

Their biggest-selling single in the UK, and one of their three No.3s, along with Robert De Niro’s Waiting and their 1989 French & Saunders (alias Lananeeneenoonoo) team-up, Help!

Preacher Man

This was co-written by Youth of Killing Joke!

Move In My Direction

A return to commercial, and some say creative, form. From 2005, their highest chart entry for 16 years.

Just the tonic

There’s no nastiness today: Bananarama deserve their place in the 80s pop pantheon. Unlike the girl groups of a subsequent generation, Bananarama weren’t stage school brats, they were DIY types who invented their own look and penned their own songs. Their sweetly shambolic sassy-pop, aided and abetted by producers Steve Jolley and Tony Swain, belied their slickness and sharpness. In a way, they were the missing link between The Slits and the Spice Girls. They seem to warm to this positioning.

“People thought we were all about ra-ra skirts and we’d get very grumpy,” Dallin frowns. Magazines would, she recalls, typecast them as airheads, handing them balloons and suchlike during photoshoots, only for the poor snapper to be given short shrift. “And then,” she moans, “we’d be termed ‘difficult’.”

“It was,” Woodward decides, “a lose-lose situation.”

Dallin remembers turning up at interviews, only to be asked, “Have you thought about writing your own material?” It still rankles. “I mean,” she says, “for god’s sake…” Were they tempted to get physical?

“God, no,” Woodward says, horrified. Actually, not that horrified. “But I did dead-leg the man from D:Ream,” she recalls of singer Peter Cunnah from the 90s dance-pop troupe for whom Things most emphatically Did Not Get Better.

“He asked whether we’d ever thought about writing our own songs. He was halfway down the stairs when I dead-legged him – he went out crying.” She laughs, then stops herself. “I’m not proud.”

They did have their champions. They became friends with George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley of Wham!, as well as, unexpectedly, goth rockers The Cure (their bassist was a huge Bananarama fan), even Def Leppard – if there was a table, the girls would regularly drink the Sheffield metal band under it.

“Part of the reason we weren’t taken seriously is that we weren’t pretentious,” Fahey ventures. Would a cocaine habit have helped change that? “Not really, no,” she replies, flicking her hair. “It’s such a bad look.”

Instead, their favourite tipple was, says Dallin, vodka and tonic. Not that things got too excessive. “There’s nothing really horribly debauched or dark [in our pasts]. None of us ended up in rehab.”

“We went out and got pissed a few times,” Woodward admits. “Every kid does that growing up.”

“We’d go dancing – we did mental dancing,” Fahey chips in, wistfully.

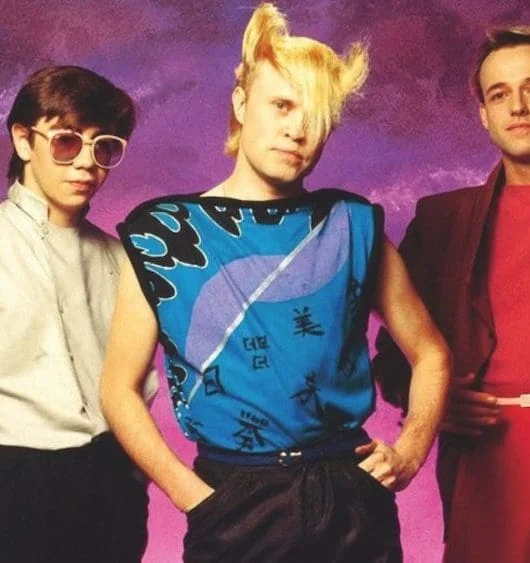

Interviewing Bananarama can mean dizzy reminiscences one minute, cultural theorising the next. They emerged out of the hothouse atmosphere of post-punk, when the dour introspection of Joy Division et al morphed into the bright colourmotion of new pop. Fahey, Dallin and Woodward absorbed the radical changes as successfully as the Martin Frys and Phil Oakeys.

“I think the 80s was the most individual decade there has ever been,” Woodward proclaims. “The 70s had glam rock, but the 80s had so many individual looks and styles. Punk gave people the freedom to express themselves.”

“The 80s were pioneering socially,” furthers Fahey, “because we were not doing what our parents thought we should do.” She giggles before her final flourish. “As Wham! said [in Wham Rap!], we were all just signing on and doing what we wanted to do: going out, dancing to music, forming bands and carving our own path.”

Fahey on Fahey

“After Bananarama, I was a bit lost for a few years, trying to express myself creatively. I’m very proud of all my Shakespears Sister records, all the way up to Songs From The Red Room [2009]. It’s just that I never particularly enjoyed the music business. As Hunter S Thompson said: “The music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs. There’s also a negative side.

“I did find you get treated like a commodity by record labels and the media, especially back then. All the early-80s artists – we all went into it for the love of music and I guess we’re all pretty iconoclastic…

“But this [reunion] is great because it’s nothing to do with record companies! It’s just a total celebration of what we created. It’s going to be really fulfilling. I can’t wait to feel the love.”

All The young punks

Many from that generation are now in control of the media. Hence the new-found respect for Bananarama. “The generation that grew up with us are now editing newspapers,” Woodward notes. “We’ve met quite a few in the last few days. There’s a new respect for us.”

Bananarama formed in 1979-80 in London, with old school friends from Bristol, Woodward and Dallin, and Fahey, who had, as the daughter of an army man, moved around a lot in her teens. Woodward was working in the pensions department of the BBC when Dallin introduced her to Fahey, who was on the same journalism course as her at the London College of Fashion.

Even at 15, Woodward had been impressed by punk – “I’d leave the house with long blonde Farah Fawcett hair and come home with it black and cropped” – as had Dallin: “My mother used to push me in doorways, embarrassed [by her hair/outfit combo].” Both, however, recoiled from the gobbing they’d see at gigs. “It was revolting,” they agree.

Fahey, being a little older, was more ready to embrace punk’s extremes. She remembers the late-70s as “a super-violent time that started with A Clockwork Orange” and an early boyfriend was Jim Reilly, drummer with Northern Irish punks Stiff Little Fingers. She loved the Ramones (“So exciting”), saw Wire’s first gig at a scout hut in Watford, followed The Clash on tour, watched aghast as skinheads laid waste to Hatfield Poly during a Specials gig, witnessed Sham 69’s last stand at the Rainbow (“It was insane, like a British Movement rally”), even slept on the floor of Kevin Rowland’s mum and dad’s house during the first Dexys tour.

Dawning of a new era

By the turn of the decade, Fahey and Dallin had evening jobs at London’s legendary Marquee club and all three were supporting, with a band called The Tea Set, the likes of Iggy Pop and The Jam. Around this time, they met Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols, who invited them to live above their old rehearsal room.

They alternated between that space and a room at the YWCA, where they got used to rats, an outside toilet, and no bath. It was a “free and bohemian” time, Fahey sighs, one of Dickensian squalor, and minor crimes such as bunking the tube. But they wouldn’t have changed a thing. “When you’re young, you like that sort of lifestyle,” Woodward says. “If you’d offered me a furnished flat I wouldn’t have wanted it.”

“I think the 80s was the most individual decade there has ever been” – Woodward

“It was a time of secondhand clothes and secondhand furniture, when we had no responsibilities and nothing to lose,” Fahey adds. “There was an underground swell of iconoclastic kids with a DIY fashion aesthetic. We all knew and influenced each other.”

They remember meeting Boy George early on, as well as a young Steve Strange, with his green spiky hair, giant Doc Martens and what Fahey remembers as a “Nazi great coat”.

Dallin recalls the transitional moment, circa 1980, when dour post-punk became a site for flamboyant peacocks, “when things all got a bit blousey”. Fahey believes the new romantic movement began a little earlier.

“Billy’s [London club] was 1978 and that was the complete inception of what became new romantic,” she insists of the burgeoning Euro-electronic scene. “Punk wasn’t authentic anymore, and everyone started going back to Bowie and listening to Kraftwerk.”

Girls aloud

It was a time of experimentation, hence the cover version of Swahili song Aie a Mwana that the girls, now calling themselves Bananarama after a millisecond as Pineapple Chunks, recorded as their debut single. John Peel played it and, as Dallin declares, “the rest is history”. They turned down overtures from The Clash’s Bernie Rhodes and the Pistols’ Malcolm McLaren to manage them. Only girls were allowed (indeed, their manager became Hillary Shaw, who later looked after Girls Aloud).

“We were living in a shared council flat, all three of us, with no money,” Woodward reminisces. “We’d got no [record company] advance, and we were still signing on, even though we were in the charts.”

Fahey relates having to go to the DHSS “with headscarves on”, so they wouldn’t be recognised after Top Of The Pops – by 1983, they’d had Top 10 hits with It Ain’t What You Do (It’s The Way That You Do It) and Really Saying Something (both collaborations with Fun Boy Three), Shy Boy, Na Na Hey Hey (Kiss Him Goodbye) and Cruel Summer. Theirs was a perfect pop trajectory, and best of all they were in control.

Woodward on Woodward

“There were some dark times in the 80s. People say, ‘Oh, you were depressed.’ We just went through life and were growing up. You have your ups and downs. Thank God we had the three of us as support, because I can see how, as a solo artist, you didn’t have that comfort blanket around you and you could go completely insane.

“There were moments when I thought, God, I just can’t do this anymore. I had a child in the middle of it – trying to cope with being a mum, being a friend, carrying on my life as normal, and doing the pop star thing as well. There’s a time when something’s got to give – I was only 25.

“I never ended up in the Priory, though. We may have had a reputation as party girls, but it never revolved around drugs. It was always a few drinks and a dance. That was our release.

“We did change after Wow! We made Pop Life, which was a big departure, and I came into my own, both as a performer and as a person. After Siobhan left, Sara and I did the world tour and it was the most amazing experience… Now we’re doing it with Siobhan!”

Top of the pops

In January 1984, they renegotiated a better record deal and bought three adjacent houses in Kentish Town, knocking through the gardens for a taste of the Beatles-circa-Help! life. They were on a roll. There were six singles on 1983 debut album Deep Sea Skiving (including poignant non-hit Cheers Then) and five on the self-titled follow-up. Fahey co-wrote Young At Heart with then-boyfriend Robert Hodgens aka Bobby Bluebell, and it became a No.8 hit in summer 1984 for The Bluebells.

They started writing songs about date rape (Robert De Niro’s Waiting), the Irish Troubles (King Of The Jungle) and drugs (Hotline To Heaven), even as they were dismissed as purveyors of fluffy pabulum. They were the only females apart from Shalamar’s Jody Watley invited to appear on Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas? -– actually not that surprisingly, the musicians they got on best with in Basing Street Studios that day were Status Quo.

It wasn’t all fun, love and money. In 1984, there was a crash of the emotional kind, after three years of non-stop recording and promoting (including in the States, where Cruel Summer was a Top 10 smash), and living in and out of each others’ pockets, finally took its toll.

“We were tired,” as Woodward puts it. In a one-on-one interview later on, she elaborates: “There were moments when I was just totally drained and exhausted. Emotionally. Because we worked so hard, here and in Europe. Then we’d fly to Japan and work for virtually 24 hours a day and then go somewhere else and be expected to be ‘on’ it… Plus we liked to enjoy ourselves. There’s

a point where you probably think, I just can’t do this anymore.”

Enter the Hit Factory…

Fahey describes 1986’s True Confessions as “our difficult third album”. It saw them commence a working relationship with Messrs Stock, Aitken and Waterman, and marked the end of the so-called shambling, DIY, Bananarama and the start of glamorous, adult Bananarama. It also included their danced-up version of Shocking Blue’s Venus. Surprisingly, it is Fahey who identifies S.A.W. as the escape route from what was looking like a creative impasse.

“As soon as we heard Dead Or Alive’s You Spin Me Round, we knew – that’s where we’re going,” she says. “I loved that record. At that point, we were all on the same page. It was like, who produced Dead Or Alive’s single? Let’s do Venus like that. We’d been struggling with that third album and we didn’t have a lead single and suddenly we had a single and it turned everything around.”

The success of Venus changed their lives – “massively,” says Woodward, who had to juggle motherhood (her son Tom was born in 1986) and international fame. It also confirmed S.A.W. as producers of their next album, Wow!

“That album consolidated everything. It was just the best pop album,” remarks Dallin, listing its singles – Love In The First Degree! I Heard A Rumour! I Want You Back! Nathan Jones! – as though even she can’t quite believe what a trove of hits it is.

… say farewell to Fahey

In early 1988, Fahey quit the group, going on to enjoy success, with Marcella Detroit, as Shakespears Sister, notably with You’re History and Stay. The latter spent eight weeks at pole position, the longest UK No.1 for an all-female band. As for Dallin and Woodward, they replaced Fahey with Jacquie O’Sullivan between 1988 and 1991, after which they operated as a duo. Since then, they’ve released some fine albums, notably 1993’s Please Yourself, 2005’s Drama and 2009’s Viva. In that time, their records and performances have been met with enthusiasm. But they would be forced to acknowledge the excitement at their return is on another level. What is it about the original three?

“I don’t know,” shrugs Woodward. “We get excited when we’re together, so I guess it rubs off.”

“We were best mates before we started the band so there’s always this bond,” Fahey adds. “It’s like a common humour.”

“Everything feels a bit like a school outing,” Dallin suggests, smiling. “It’s like when you’re excited getting on the back of the coach with your mates. It always feels like that.”

Dallin may be 55, Woodward 56 and Fahey 58 (although they could each pass for a decade younger), and the voluminous frazzled coifs and thrift-shop wear may have been replaced by sophisticated tresses and elegant designer apparel, yet still they have about them the air of casual subterfuge. Is there mischief involved?

“Yes!” they reply as one.

Do they make people nervous?

“Apparently, we used to,” Woodward says. “The amount of people we’ve met who’ve said, ‘Oh god, I was so scared of you!’ Because we were very shy we moved as a team, and I think that was quite intimidating.”

“Shyness can sometimes appear to be rude,” Dallin muses.

“And we’d be constantly quipping to each other, and erupting, and nobody knew what we were laughing about so it made them uncomfortable,” Fahey laughs.

Fun girl three

Bananarama have recaptured the playfulness of their early days. Where before there was enmity, now there is fun. In 2015, a photo taken at London’s Soho House appeared on Twitter of the girls, smiling broadly, with Boy George. Around that time, there was an informal gathering at Fahey’s in East London.

“We hadn’t talked about doing anything at that point,” Dallin says. “We went to Siobhan’s house in Bethnal Green where we had a little barbie and some wine, and discussed maybe doing a Christmas show, but it never came about.”

“It’s about love, friendship and a celebration of what we created together.” – Fahey

At another get-together, Woodward says, they danced to 70s disco and funk in Fahey’s kitchen, “which turned into rock’n’roll and ended with me punching the air, as these things do,” Fahey finishes her sentence, as all three tend to do.

Nothing was tabled, although Dallin and Woodward, as veterans of the global gig and festival circuit, did tempt Fahey – who left Bananarama ahead of their 1989 world tour; before, indeed, they ever toured as a three-piece – by telling her about the love they got from audiences. But she still wasn’t convinced it was the right thing to do.

“I think,” Woodward observes, recalling, perhaps, the frictional relationship between Fahey and Pete Waterman, “when Siobhan left, the music business was very different. [Addressing her] You always felt as though you were battling against everyone, in a man’s world.”

Later, Dallin opens up about the split. She remembers “a lot of sulking” from all concerned, and both parties “talking to each other less”.

“I guess Siobhan wanted to do different music,” she says, still smarting a little, “but that was, like, well, you stay with your poppy thing. But we went on to do [1991’s] Pop Life – I really like some of the albums we did on our own. I just think we evolved in different ways. She’d just had enough and wanted to move into something else, and we were very happy with that.”

Has hell finally frozen over? She laughs but doesn’t respond. Then, on a more positive note, she says: “I never imagined I’d ever do anything with Siobhan again, but it couldn’t be more fun. It’s like she never left. It’s fantastic.”

Dallin on Dallin

“I absolutely loved being a duo. It was quite a lean period in the 90s, commercially, and then in the Noughties we started to tour and made Drama and Viva – I love those albums. We established ourself as a touring band and went all over the world. So when people say, oh, it’s a comeback – it’s not quite like that.

“I think Siobhan and I are quite similar, which is probably why Keren was my friend, because she balanced things out. I was always quite driven, writing songs and coming up with ideas. I’m not saying that Keren didn’t, but I think Siobhan and I were quite ambitious and Keren was far more easy-going. I’d be worrying about things whereas Keren would go with theflow. I’ve been very lucky to do this since I was 18 years old, and now I’m in my 50s. Who knew?”

“I absolutely loved being a duo. It was quite a lean period in the 90s, commercially, and then in the Noughties we started to tour and made Drama and Viva – I love those albums. We established ourself as a touring band and went all over the world. So when people say, oh, it’s a comeback – it’s not quite like that.

“I think Siobhan and I are quite similar, which is probably why Keren was my friend, because she balanced things out. I was always quite driven, writing songs and coming up with ideas.

I’m not saying that Keren didn’t, but I think Siobhan and I were quite ambitious and Keren was far more easy-going. I’d be worrying about things whereas Keren would go with the flow. I’ve been very lucky to do this since I was 18 years old, and now I’m in my 50s. Who knew?”

Sister does it for herself

Once “free”, Fahey probably struggled more than Dallin and Woodward ever knew. Not only did she have to adjust to life on her own, she had to maintain the momentum of Stay. Attempting to repeat its success, exacerbated by “issues” with Marcella Detroit, she suffered a breakdown. “It was a difficult partnership,” she says of SS. “It was horrible to build something up, then to have to walk away from it. That was quite shattering.”

Is she the Troubled One in Bananarama? “I think I’m a very sensitive person,” she allows, slipping into US therapy-speak with a chuckle. “I’m working on that… I’m hyper-sensitive and I became depressed. But I’m fine now.”

This must, Classic Pop suggests, be like coming home. “Oh my god,” she gushes. “So like coming home. It’s like going in a time-tunnel, back to my roots.”

Is there a sense of unfinished business, and closure?

“Yeah, totally, even though I didn’t ever anticipate this would happen. I didn’t anticipate a situation where it would feel right. But over the last few years, whenever we’ve seen each other, it’s been like a soulmate thing. The band came out of our best friendship.”

Did you have to do any apologising? “To my significant others?” she asks, wryly. “There was no need. Time did its work, and then I think we got to the point where we forgot how or why we even got like that. We spent nine years together as best friends, living together, going out everywhere socially, sharing the same friends, and, of course, having the band.

“That meant we were together 24/7, and that’s a real intense pressure-cooker. Not many marriages or friendships could sustain that much time together.

“Listen, I love them dearly,” she confides, listing some of the reasons for the split. “I just needed to move on at that particular point. Our relationship as friends was under a lot of strain, they started to do stuff socially without me and I felt kind of lost. Plus I wanted to do something that was a bit edgier. I think Wow! is a great record but I found working with S.A.W. we got into a production line mentality. I wanted to work in a way that was more organic and personal. I needed to do that at that particular point in my life and I need to do this at this particular point in my life.

“I realised when I came back to talk to Sara and Keren that I’d actually walked away from a big part of my identity when I left the band. I realised I will always be Siobhan from Bananarama, and I’m very emotional about it. And excited. It’s nothing to do with, ‘Let’s get together and make some money.’ It’s about love, friendship and a celebration of what we created together.

“We really love each other. They [pointing to Dallin and Woodward] said, ‘You’ve no idea what we brought to the world – you should experience it.’ Well, why not? I’m ready for a bit of love.”