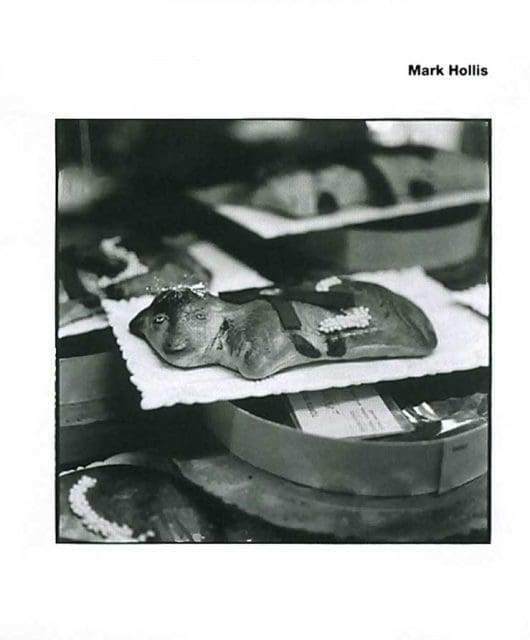

Making The Sundays: Reading, Writing And Arithmetic

By Classic Pop | February 14, 2022

Mixing the feathery whimsy of the Cocteau Twins and the jangling melodicism of The Smiths, The Sundays were tipped for huge stardom with Reading, Writing And Arithmetic. Only problem was: they weren’t ready to play the pop game… By Neil Crossley

The Sundays were pretty rubbish at being pop stars. No glitzy aspirational image, barely did interviews, low-key videos, and a less-than-showy live show… Only thing is: The Sundays made near-celestial pop music. In a career that never reached its promise, they released only three albums: this, their 1990 debut; 1992’s Blind and Static & Silence five years later. After that, The Sundays simply stopped.

Of course, whether The Sundays were ‘pop’ very much depends on one’s definition. The Sundays weren’t even that popular: only one Top 20 single, Summertime, from their swansong album and they were barely recognisable as stars, other than to those who adored them. But they were very ‘pop’ in that alternative/indie way, and one of the most melodically beautiful bands of their era.

When they emerged in 1988-89, indie pop and UK pop in general – was undergoing something of a spin around. Guardians of the student galaxy, The Smiths, had recently split. On the rise were a much more hedonistic indie bunch in the shape of nascent ‘Madchester’ bands Happy Mondays and The Stone Roses.

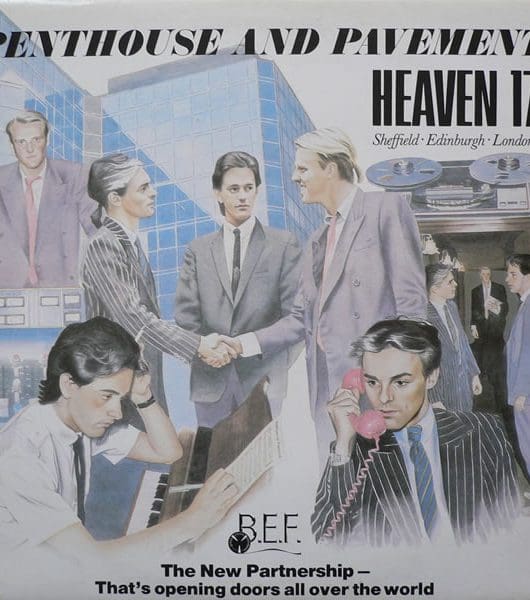

Mainstream pop was sweating to the sounds of early house and the Hi-NRG puppets of Stock Aitken Waterman, and even Paul Weller had gone all Italiano sophisticate (white jeans, anyone?). Dance culture was very much back in.

By contrast, The Sundays sounded like something still lurking in the darker days of 1984 and anti-Maggie resentment/escapism. As writer/broadcaster Stuart Maconie notes in his 2013 book, The People’s Songs: The Story Of Modern Britain In 50 Records: “Indie offered a different narrative to the one that is generally seen as the story of the 1980s: vintage clothes, old records, bedsits, Penguin Modern Classics, black and white movies, instead of the Champagne, Filofaxes and outsize mobile phones of Thatcher’s children.” Spot on.

Although a four-piece, The Sundays were essentially the work of a partnership, both professional and personal.

David Gavurin met Harriet Wheeler at Bristol University and soon became intertwined. He was reading Romantic Languages; she, English Literature. So, if The Sundays were an archetypal ‘student band’ that’s because they were, indeed, archetypal students.

The Sundays’ rise was remarkably rapid. The foursome formed in 1988 and just a month after their first gig they’d debuted at Camden indie sanctuary The Falcon to sky-high praise.

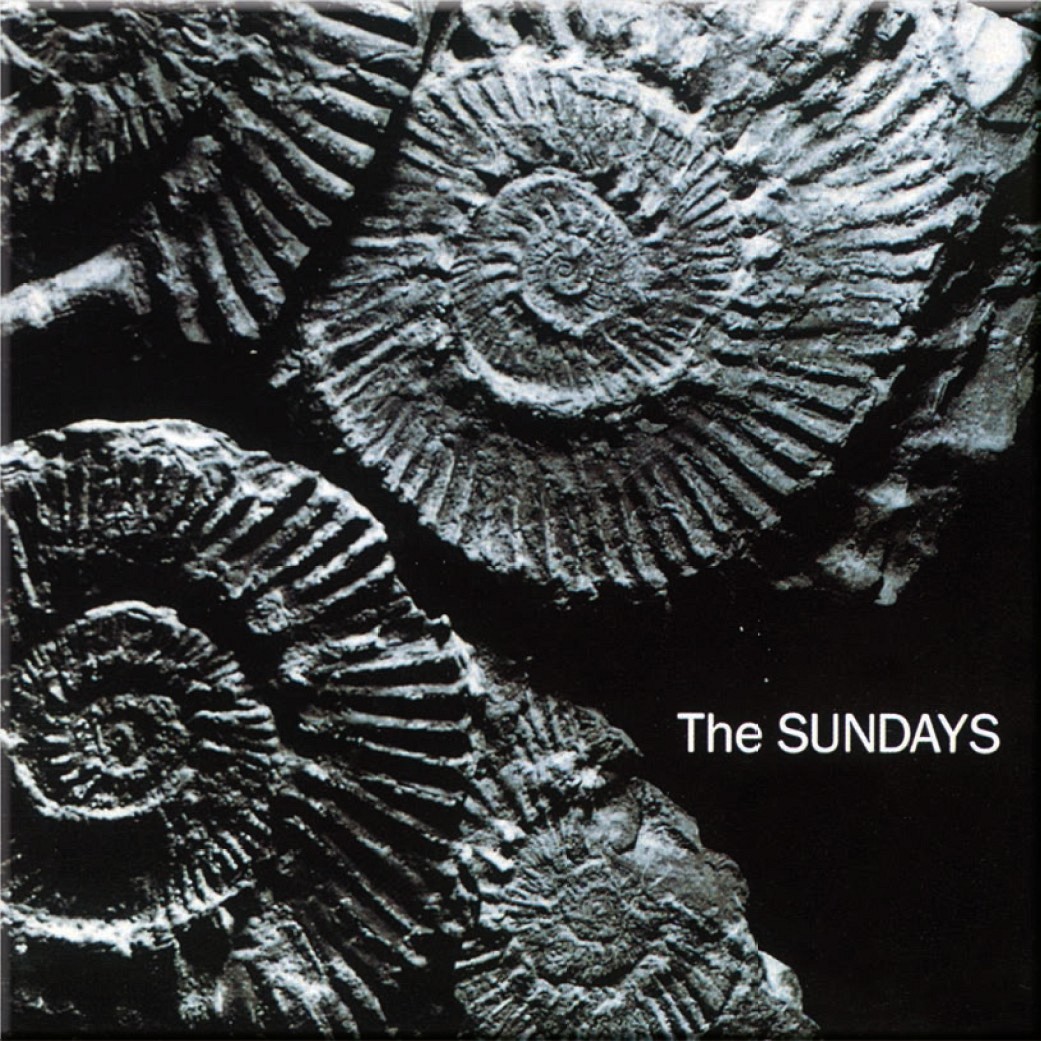

Melody Maker’s reviewer Chris Roberts described the band as “the best thing I’ve ever heard”, and comparisons to the Cocteau Twins, Smiths and Sugarcubes were duly made. Before you could shout “black cardigans!”, a label bidding war for The Sundays was raging.

The thing is, The Sundays didn’t really have enough songs for an album at this point. In one of their extremely rare public utterances, a Melody Maker interview to promote the release of Reading, Writing And Arithmetic… in January 1990, they explained how they were almost devoid of ambition beyond the noise they made.

The players

Gavurin, born 1963, studied Romantic Languages at Bristol University, and became creatively and romantically involved with Wheeler in the mid-80s. The two formed The Sundays as a project in 1988. Gavurin had self-taught himself guitar in his teens and, trivia fans, is one of the best friends of comedian/writer David Baddiel from schooldays – the two were even in a teen band together. Lesser known fact? According to Baddiel, Gavurin introduced the comic to the music of one of his favourite bands – mid-70s-era Genesis.

Wheeler studied English Literature at Bristol University. She was also born in 1963, the daughter of an architect and a teacher. Wheeler grew up in Sonning Common, near Henley-on-Thames, before attending Bristol Uni and sang in a band called Jim Jiminee before meeting Gavurin, though they only got as far as far releasing demos to various London clubs. Alongside husband David, she ‘retired’ from releasing music post-1997 to focus on their family.

Another Bristol University student, drafted in after Gavurin and Wheeler had started writing together. Brindley’s leaping, melodic basslines were pivotal to The Sundays’ sound, although he was never given a co-writing credit. After the band drifted to a halt he remained in the industry, founding a digital music research company. As someone ‘relatively’ contactable via email, Brindley has became a go-to for fans constantly asking about any future Sundays music. He’ll sometimes answer, but is consistent: there are no plans.

The final Sundays member was another Bristol Uni sidekick. After The Sundays, Hannan went on to join Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s Britpop-era band theaudience as drummer and was a co-producer on the outfit’s only, self-titled album (1998). Hannan has also played drums with Robyn Hitchcock and ex-Katrina And The Waves member (and Walking On Sunshine writer) Kimberley Rew. He can be found on Twitter via @patchhannan.

Gavurin concurred that although they liked playing live, writing songs was, in reality, their only goal. “If we hadn’t been so bloody lucky enough with getting all those reviews right at the start, I could imagine a situation where we wouldn’t have stuck at this for bloody ages.”

“Bloody ages?” They were just 18 months old as a band. Wheeler notably said there was “never a time I wanted to be incredibly famous or in a pop group” although she did confess to pretending to be Michael Jackson as a girl: “which took quite a leap of faith.”

Read more: The complete guide to The Smiths

Read more: The Lowdown – Morrissey

After that London debut (the band had moved to the capital), The Sundays were destined for an indie big-hitter: 4AD, home of the Cocteau Twins, or Rough Trade, previous home of The Smiths. Naturally. 4AD were in pole-position until owner Ivo Watts-Russell foolishly asked Gavurin and Wheeler to think carefully about which label to sign with. They bluntly answered: Rough Trade.

In Neil Taylor’s 2010 book, An Intimate History Of Rough Trade, Gavurin argued – possibly joked – that The Sundays chose to sign to Rough Trade because “it was near our flat.” When the band first met RT’s co-directors Geoff Travis and Jeannette Lee, who had only joined the company in 1987, immediate impressions were positive.

Lee had previously been a member of John Lydon’s Public Image Ltd, was married to Gareth Sager of The Pop Group, and had a solid knowledge of Rough Trade’s post-punk modus operandi. In the book, Gavurin is quoted as saying: “What appealed to us about the two of them was that they seemed incredibly straightforward… For us, Rough Trade was this immensely cool and significant label, yet there was no arrogance about them. They basically came over as a couple of unassuming music fans.”

“The Sundays were very particular about making decisions,” Jeannette Lee tells Classic Pop. “They wanted to talk in great detail about everything before they decided who to sign for – what the singles would be, the artwork… Maybe what Ivo Watts-Russell asked them was 4AD’s downfall. After that, I made a mental note never to use that tactic when trying to sign a band!”

Perhaps tellingly, The Sundays chose previous Smiths sleeve designer Jo Slee and decided their own touring schedule. Debut single Can’t Be Sure, backed with I Kicked A Boy, was released in January 1989 and – as was in “the indie rules” of the day – the BBC’s John Peel was an early champion. The single only peaked at No.45 in the UK chart, but that was a pretty good result for a label such as Rough Trade.

Still, The Sundays were happy at the record label. “The culture seemed to be one of openness and co-operation,” continued Gavurin in Taylor’s book, “and we got on well with everyone there. We used to walk down Caledonia Road, and it became a sort of home-from-home.”

Lee remembers it as simply fun.

“They knew what they were doing was good. But they were very careful not to seem smug or overly confident. They’re both self-deprecating and you can hear that in the words. They’re both the funniest people, and we had such a laugh making that record. Obviously, they are a couple but they’re a very good working couple as well. A very solid double act.”

Rumours that the album took a year to record are wide of the mark, though. “Oh, no, that would never have been the plan,” adds Jeannette Lee. “They were particular, they are slow. But only because they wanted to be very certain about what they put out. Some people just record and fling something out and see what happens. Not The Sundays. They are perfectionists.”

In a 2014 email interview with American Way, Gavurin and Wheeler explained of Reading, Writing And Arithmetic, “As writers, the odd thing is that you’re as likely to think back to the place where the songs were actually composed as to any location or situation that inspired their creation. So in the case of Can’t Be Sure and Here’s Where The Story Ends in particular, these songs transport us to the minuscule boiler room attached to the equally cramped rented flat we were living in before our careers took off.

Read more: Top 20 side projects

Read more: Debbie Harry on film

“At the time, despite the industrial noise of the hot-water system and the frequent burglaries, this felt like the perfect writing environment, and virtually all of what ended up on our first album originated there. Not very poetic, but there you have it!”

The album sold well but, regrettably, trouble was ahead. Rough Trade’s financial strife with their distribution arm meant The Sundays, who had only just appointed a manager, soon had to leave to realise even the ambition of another record. “We had long-term hopes with them, obviously,” says Lee.

“We were very close and had talked a lot about the second album. But between that first record being released and the second, that’s when all Rough Trade’s distribution problems occurred. I just remember one day David saying, ‘Let’s not talk about the second album at the moment because there’s a problem we need to look at’.

“I realised we were going to lose them. No hard feelings at all, they had no choice really, but it was heartbreaking.”

The Sundays moved to Parlophone, and followed up with Blind (1992). And, after a long hiatus due to children, Static & Silence (1997). But then they simply stopped making records. They do still write, but said to American Way: “First, let’s see if the music we’re currently writing ever sees the light of day.”

Settled down with 20-something children, and with a reliable heating system, maybe they’ve now just run out of things to write about.

A shame, maybe, but it’s worth revisiting Gavurin’s interview words from 1990: “Non-events are almost sneered at,” he mused. “You don’t see big movies about non-events…”

Read more: Top 40 Kate Bush songs

The Sundays: Reading, Writing And Arithmetic – The songs

1 SKIN AND BONES

A remarkable opener. The drums seem distant, almost padded, Gavurin’s guitar explores simple one-note chimes (albeit with incredibly precise bends) and it’s in anything but a straight 4/4 rhythm. Oh, and these are some lyrics: “Oh, you see me in a cardigan/ In a dress, dress, dress that I’ve been sick on/ Oh, how are you?/ Can’t say I really care at the end of it all”. It could be another night of student shame, with the caveat: I’m only human! Embarrassment and self-deprecation soon emerges as a strong Sundays theme. Rick Astley didn’t write songs like this.

2 HERE’S WHERE THE STORY ENDS

A much more trad-sounding shuffle that echoes the “new Morrissey/Marr” comparisons, mainly due to Gavurin’s guitar. Seems to be about another doomed fling, though the progress of words from “It’s that little souvenir of a terrible year” to “… of a colourful year” suggests all shame is eventually laughed off. It was a US hit, eventually: it was never released as a Sundays UK single due to Rough Trade’s distribution collapse, but Tin Tin Out had a UK No.7 with an anaemic ‘dance’ remake in 1998. The allusion to embarrassment in a shed suggests Wheeler has either a vivid imagination or she’s not making these dalliances up.

3 CAN’T BE SURE

The Sundays’ debut single was another example of usurping pop convention. As often with The Sundays, the chords are mostly implied by the bass, Gavurin’s guitar being “non-resolving” arpeggios and single notes, and Patch Hannan’s eager tom-tom drums only properly take off two thirds in. It’s thus impossible to dance to: an indie shuffle would have to suffice. Wheeler’s trembling lament of “England my country, the home of the free/ Such miserable weather/ But England’s as happy as England can be/ Why cry?” is Morrissey-esque.

4 I WON

More muscly 4/4 rock than most of Reading, Writing And Arithmetic‘s tracks (the Peel Sessions version is tough), it’s suggested by some fans this re-tells the horrors of housesharing: “I won the war in the sitting room/ I won the war but it cost me” and “God only knows why it’s so hard to get to sleep in my house.” Is Harriet’s housemate a rich benefactor worth suffering, though? Maybe so. “It’s not difficult to see that you’re/ Young and selfish, with liberty and money/ Don’t go!” Must be the only song ever with a bridge falsetto of “Oh, your supercilious smile.”

5 HIDEOUS TOWNS

Ah, some levity. Barmy lyrics about joining The Salvation Army, the Civil Service and going to Piccadilly Circus (“I took the first bus home”) reiterate ‘outsider’ status, but well-knowing: “My hopeless youth it’s just so uncouth” echoes the notion that wisdom, as in Can’t Be Sure, will come later. Gavurin’s scratchy jangle is very mid-80s indie and Paul Brindley’s bassline is a close relation of Hollow Horse by The Icicle Works, early ‘dream pop’ explorers of 1983-84.

6 YOU’RE NOT THE ONLY ONE I KNOW

A genuinely swooning song kicks off (in old money) ‘Side 2’, confronting a scene, it seems, where Wheeler is defiantly surviving a split. Again, it’s hardly a conventional lyric – “What’s so wrong with reading my stars/ When I’ll be in the lavatory/ And what is so wrong with counting the cars/ When I’m all alone” – though such musings could barely be sung more delicately. This is the hazy voice that made Wheeler (in the words of The Independent) “every sappy student’s pin-up of choice”. Meant as a compliment, we’re sure.

7 A CERTAIN SOMEONE

In which The Sundays get their white funk on: Gavurin’s guitar break has nods to Johnny Marr and The Smiths’ Barbarism Begins At Home and The Draize Train. Wheeler appears to be pondering the banality of marriage (“wash your clothes, change your name”) while admitting it could change for “a certain someone”. The closing “I’ll never believe what we’ve found / We figured it out, we figured it out/ We lived in a house, in a cold room” seems to echo the couple’s domesticity. Wheeler’s coda vocals soar like fireworks.

8 I KICKED A BOY

Concisely waltzing guitar pop, that reads like a light-hearted confessional. “When the weather’s fine, when it’s sunny outside/ Think about the time I kicked a boy ’til he cried/ Oh, I could’ve been wrong, but I don’t think I was/ He’s such a child.” Bit harsh! It should be noted that Gavurin also wrote lyrics, thus making Sundays songs sometimes gender-fluid. But we don’t imagine he penned this one. Did he?

9 MY FINEST HOUR

Another fan favourite, and full again of selfmockery in “The finest hour that I’ve ever known/ Was finding a pound on the underground”. “I was a bit shocked at that lyric, frankly,” laughs Jeannette Lee. “I thought it was going to be more profound than that! It was part of the appeal, though, they were as normal as possible… while still being interesting. We all loved that song.” More superbly jangling guitar from Gavurin.

10 JOY

One of the last songs written for the album, closer Joy is The Sundays at their most abstract. Again led by a circular bassline, it sounds more like a loose jam. The lyrics – it begins with “The Lone Ranger sold his wardrobe/ The Lone Ranger sold his bad dog” and ends with “work harder, work harder, you say” – fit what Gavurin called the band’s ‘impressionism’. It ends the album with a harder, droning squall of electric guitars, more reminiscent of My Bloody Valentine than the other-worldy folkiness of the rest of the LP. “They originally wanted to call the album Joy,” says Jeannette Lee, “but someone else had used it, I can’t remember who.” Joy was still performed as an encore during The Sundays’ final 1997 tour.

Wheeler explained that: “Things don’t come mentally easy for us, we have to work on them until we feel they’re ready. It occurred to us that it was good, but we never had any enormous confidence that other people would like it… or wouldn’t like it.”

Read more: Johnny Marr interview