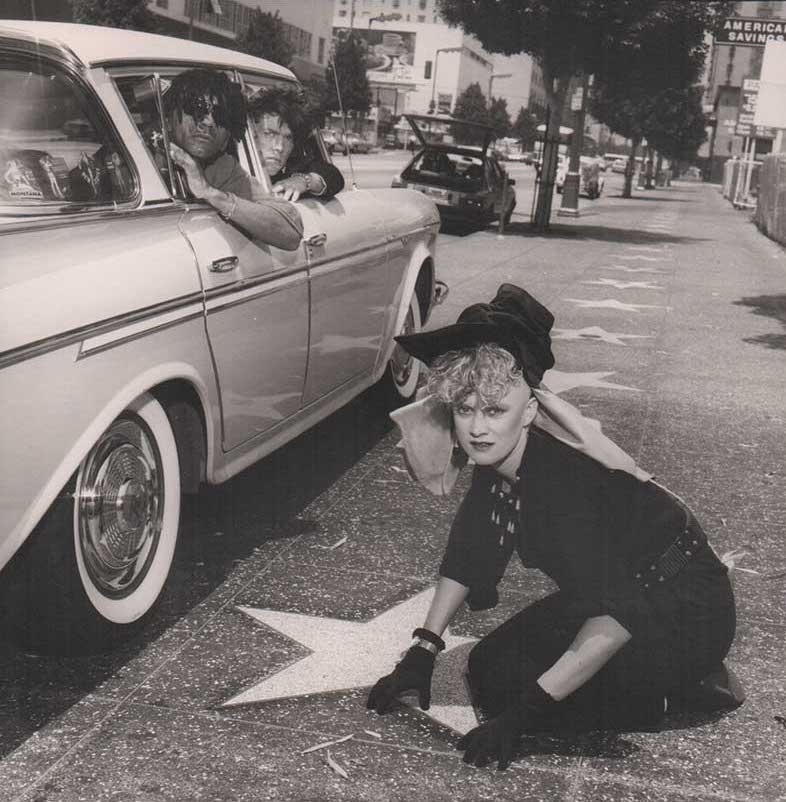

Alannah Currie in LA

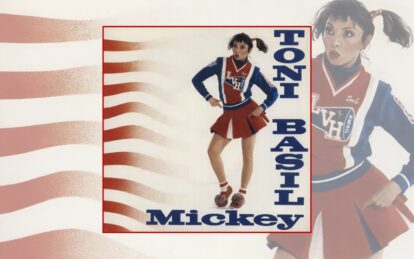

In this archive interview from 2017, Thompson Twins’ Alannah Currie remembers the band’s early days… By Jenny Valentish

Behind the imposing doorway of the Sisters HQ in Borough, south London, is a four-storey hive of mischief.

The workshop is the enclave of Alannah Currie, one of pop’s great dissenters, and her shadowy feminist army, the Sisters of Perpetual Resistance.

It’s strewn with furniture she builds, and silk protest banners, stitched with expletives.

The basement belongs to her husband, Jimmy Cauty, who creates post-riot landscapes in miniature, along with riot shields bearing the ‘Smiley’ symbol of acid house – the genre he once dominated with The KLF.

Currie leads the way upstairs to a lush living area adorned with branches, regal armchairs with feathers spewing from bullet holes in their backs, and a wall of books about dead artists and poets.

As she serves tea in best china to Classic Pop, she’s explaining why she’s doesn’t normally do this sort of thing.

“The thing that I’m always seeking out is the feeling of the finger on the trigger, the moment that contains the huge potential,” she says. “Nostalgia is only good for storytelling. It lacks the potential for an explosion.”

Yet if you don’t tell your own story, others will. “I get fed up of reading other people’s versions of what I did,” she says. “My little world is all very subjective.”

Currie may be living only five tube stops from the squat where her Thompson Twins journey began, but her “little world” would take most people several lifetimes to explore.

She grew up in New Zealand, which, in the Sixties and Seventies, was at no risk of being flooded with youth culture. Currie’s father worked as a docker at Auckland’s Queen Street Wharf.

“That was his official job,” she says dryly. “His unofficial job was as an illegal bookie. My weekend visits were often spent at the racetrack carrying large rolls of cash for him and meeting dodgy blokes to pick up brown paper bags full of money.

“In the end, he got arrested in the middle of the night and had to walk up Queen Street in his pyjamas.”

Her father left when she was five, leaving her socialist mother to raise five kids in a council house. Currie told her mother’s story in Sister Of Mercy, from 1984’s Into The Gap.

“My father was a very violent man and Mum said to me many times, ‘I would have killed him with a knife, but I didn’t because I had to look after you.’”

Alannah Currie and Tom Bailey, 1981

Currie’s grandmother was a force of nature, too, with tales of having been a housemaid in London during the Suffragette movement and wearing red petticoats in solidarity.

Her influence may have indirectly caused Curt Smith of Tears For Fears to complain years later to Smash Hits that he couldn’t fancy Currie because “she takes feminism to ludicrous extremes”.

Not that Currie would care. She considered herself a working artist, not a pin-up. Her feminist stance, like the layered clothes and oversized duckbill cap, were a two-fingered salute to mainstream expectations.

- Read more: Thompson Twins / Tom Bailey – album by album

Currie came to London in 1977, attracted not by the music scene, but by the notion of squatting.

“I had two friends who were here, and they wrote and said: ‘We have this house; it’s free. The government owns it.’ I arrived at Heathrow with a postie bag and £300.

“The taxi drove through Chelsea and I thought, oh yes, this is exactly what my grandmother had talked about: beautiful houses, roses round the door.”

The taxi kept going until it reached Brixton, where the houses were barricaded with corrugated iron. Currie’s squat-to-be, in Park Court, was above an illegal amyl nitrate lab.

From afar, punk had looked like a revolution. Up close, in Sloane Square, Currie was disappointed.

“They were all makeup and big hair-dos. I thought, ‘Well, this is no revolution. This is just fashion.’”

Nevertheless, Currie formed her own band, The Unfuckables, with her friend Trace Newton-Ingham and a rotating cast. “We used to play anti-music,” she says. “The idea of having to stay within prescribed rhythms and scales didn’t appeal to me.”

Their sole gig, at London’s Conway Hall, saw their number swelled by The Slits’ Viv Albertine, The Pop Group’s Gareth Sager (whose sax playing inspired Currie to start), members of This Heat, Steve Beresford and Jimmy Cauty.

Tom Bailey also put in an appearance. He was in a Sheffield band, Thompson Twins, that had moved into the squat opposite Currie’s. She and Newton-Ingham watched them move in, eyeing up the PA system like two alley cats on a wall.

“I didn’t think they were my type of people; I just fancied their gear,” she says. “But I became good friends with Tom and that eventually became a love affair.”

She met Joe Leeway at a dinner party, where she recalls him grandstanding about wanting to live in a squat. “I’ll help you,” she offered, calling his bluff.

Leeway’s chief interests were theatre and beat poetry, but he wound up joining Thompson Twins, along with Currie, for the second album, Set.

Drifting away from the other band members, the trio set up a side project, The Black Arabs, based on the reggae soundsystems they’d check out in Brixton.

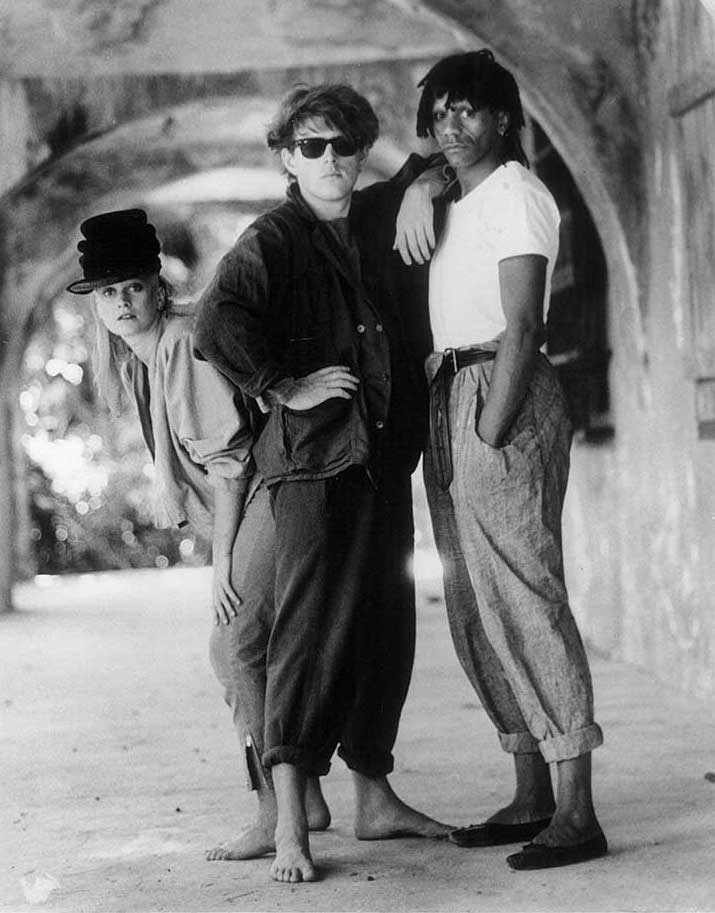

The trio of Alannah Currie, Tom Bailey and Joe Leeway, a format which lasted from 1982-1986: “We gave ourselves 18 months to do it”

In 1982, Thompson Twins released the Steve Lillywhite-produced single In The Name Of Love, which became an overnight No. 1 on the US dance chart, staying at that spot for five weeks.

“Tom had moved into synths and drum machines and he was so excited about being able to construct stuff,” Currie says of their new direction.

They hoped to marry the funk of Talking Heads with Kraftwerk electronica and reggae rhythms, with the aim of chart domination.

- Read more: 1983 in music

However, whether or not the original members saw Currie as a Yoko Ono figure, dissent was swelling. When the LP tour finished, Bailey, Currie and Leeway decided to start again as Thompson Twins MkII.

“We gave ourselves 18 months: ‘Let’s just do it, with the most intention and integrity we can’,” Currie recalls. “Tom and Joe wanted to be on Top Of The Pops… I just wanted to see if I could do it on my terms.”

Even with a new deal with Arista, the trio continued to live in squalor. “They would send limos to the squat to pick us up. I had no idea we were paying for them.

“Everyone else in the street would leap in the limo, too, legs and arms sticking out of the window, going three times round the block before we had to go to work.”

The British inkies weren’t impressed. “We started on a bad foot, crossing the line from grungy squatter band into pop,” says Currie. “That was an enormous sell-out in the eyes of various music journalists.”

Still, who cares? Their next album, Quick Step And Side Kick, reached No. 2, later going platinum.

“Feeling like a commodity didn’t happen until 1985,” Currie reflects. “There were a good couple of years when we had a real laugh and it was exciting. The three of us were interested in the things that bound us, as opposed to our differences.”

That included messing with gender ideas, with Currie writing lyrics for Bailey to sing. She also employed as many women as she could.

“It’s different now, but when you toured clubs, there’d be pictures of naked women all over the walls. I’d say, ‘Cover them up. I’m not going to stand beside them and have everyone gawking’.”

The band clocked up magazine covers and high-profile concerts (including a Philadelphia Live Aid performance with Madonna on BVs), also attracting their fair share of crazed fans.

“Someone cut off Tom’s hair with scissors after a gig so she could keep it,” Currie says. “He had this long hair and some girl just went: snip. At least she didn’t stab him.”

Manager John Hade controlled the kitty, giving each member a weekly wage and the odd wedge of cash to Currie so that she could orchestrate the tour wardrobes.

The band weren’t in the habit of scanning spreadsheets. “After selling millions of records and touring the world, we had accountants saying, ‘You’ve got to take some sort of involvement because you’re just about to go bankrupt’,” Currie says.

Further strain came with the making of 1985’s Here’s To Future Days, originally self-produced in Paris, but rejected by the label.

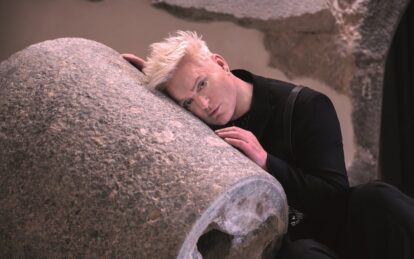

Thompson Twins – with Alannah Currie – in 1991 at the time of the Queer album, previewed by Tom’s ‘Feedback Max’ dance mix identity

Despite Bailey suffering from nervous exhaustion, the band remade the album with Nile Rodgers.

“Nile is a fantastic musician, but he wasn’t at that time into experimenting with sound,” says Currie. “He makes records like Nile. He and Tom got on okay, but Joe and I were redundant, and that was really painful.”

Not long after, Leeway left the band, eventually starting a neurolinguistic programming training company in California.

Currie and Bailey continued as a duo, enlisting a new manager, Gary Kurfirst, who had worked with the Ramones, Blondie and Eurythmics.

“He was fantastic, really naughty,” Currie recalls. “I remember his first outing with us, to Russia, because he got terribly drunk. Tom had to carry him out of the club through three feet of snow and drag him back to his hotel.”

But inspiration was increasingly elusive. “The first time we toured America we got invited to the wildest clubs in New York and LA and were up all night,” she says of the flurry of celebrity engagements: breakfast with Timothy Leary, dinner with Andy Warhol.

“Then you have security and you’re in Park Lane Hotel and you don’t get to meet people. You’re in these towns and you don’t know you’re there. It’s boring. We had very little to write about. I lost interest completely.”

Currie and Bailey had a son, Jackson, followed five years later by daughter Indigo. They were living in an old Victorian asylum in Wandsworth, during which time they released an electronic album, as Babble.

Then they decided to “go feral” and move to wild and woolly bush land in Tawharanui Peninsula, New Zealand.

“We thought we could operate the band by internet, so we built this crazy wedding cake of a house in the side of a cliff. The rain came down. Picture scenes from The Piano.”

Currie says she didn’t change out of her Vivienne Westwood boots for a whole year, despite the constant deluge of mud.

“We had Polaroid pictures of our London place. I used to look at them and think, ‘Ooh, I used to be a pop star. What have we done to ourselves?’ Tom got depressed, hid under the stairs and meditated for three hours a day.”

Alannah Currie

Their second and final Babble album failed to set the world alight. Nevertheless, the pair wrote a swathe of songs for other artists, including Debbie Harry (I Want That Man) and Traci Lords.

When Bailey started his own dub project, International Observer, Currie threw herself into glass art and environmental activism, founding the rabble-rousing Mothers Against Genetic Engineering (MAdGE).

After 10 years in New Zealand, Currie and Bailey split in 2004 and returned separately to London.

Now the ‘ex’ tours as ‘Thompson Twins’ Tom Bailey’, which Currie’s disappointed about because it scuppers her idea of: “Go to China and hire musicians to create a band, teach them our old songs, mix in some Chinese opera and grime, update the visuals, then run it as a mad-production world tour.”

But of the two bandmates with whom she lived in that strange bubble, she says approvingly, “It was a great three-piece play. We really liked each other. We loved each other.”

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.