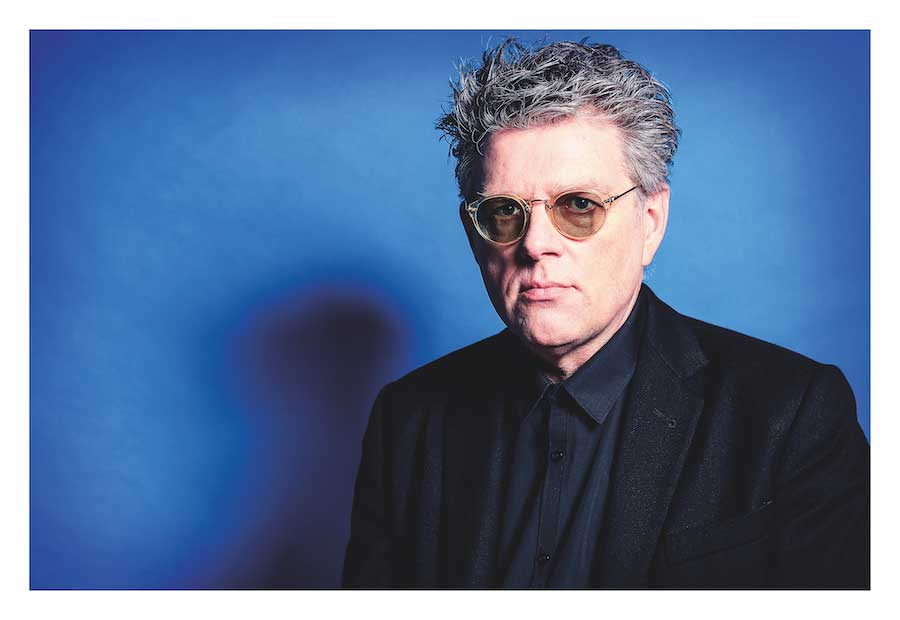

Tom Bailey interview: “It can be harder to write pop when you’re older”

By John Earls | February 7, 2023

Previously a cult proposition across the albums A Product Of… and Set, US hit In The Name Of Love inspired Tom Bailey to transform Thompson Twins from a seven-piece cult collective into a streamlined pop trio featuring Alannah Currie and Joe Leeway on 1983 classic Quick Step & Side Kick. Tom reflects on the price of hard work and why he’s eager to make up for lost time on his return to pop…

How did you come to slim Thompson Twins’ line-up down to a three-piece for Quick Step & Side Kick?

After two albums, I was tired of waiting to see if it might happen for us. I thought: “Why don’t we just make sure it does happen?” Set’s producer, Steve Lillywhite, does a lecture tour about the music business. It’s apparently very good, and Steve says in it that the only single he made with a drum machine was In The Name Of Love.

I only wrote that song as filler for Side Two of Set because I didn’t have enough material for the band, and it became a big US hit. It was the signpost record telling me I had to get away from the original band.

I didn’t want to get away from that music or the people in the band, it was just that the way we were doing things wasn’t going to do it for me. In the tour, Steve also says I fired everyone in the band who was a musician and kept the ones who weren’t.

It’s a funny line, but in a way it’s true. I didn’t want Thompson Twins to be encumbered by: “I’ve got to find a nice part for the drummer to play.” I went straight for obvious pop, with a drum machine: kick, snare/kick, snare. I wrote music around that.

How hard was it to achieve that new style in reality?

We’d go into a writing session and think: “We need four of these songs to be hits.” We clarified our vision, forcing ourselves to be clearer than was comfortable. We said that, if we didn’t have a Top 10 hit in the next year, we had to dissolve the band. We put that pressure on ourselves to stop the what ifs and maybes in everything we’d done before.

That might sound scheming, but we had a division of labour between the three of us. I did the music, Alannah wrote lyrics and directed our visual imagery, while Joe used his theatrical background to design our amazing stage show. We became an industry, a force of nature. We became kind-of orphans. We’d work on Christmas Day and wouldn’t go home.

You certainly gave the record company plenty of options. In addition to the hits, Quick Step

& Side Kick has more potential singles such as Love Lies Bleeding, If You Were Here and Judy Do.

If You Were Here became famous after it was used in Sixteen Candles, and is usually the only song I play that’s not a single. We had to work hard to get our hits, but it means you enjoy that success when it comes.

- Read more: Thompson Twins / Tom Bailey – album by album

How important was your producer, Alex Sadkin, in Quick Step & Side Kick’s success? Because he died in a car crash in 1987 when he was only 38, it feels like he’s the great forgotten producer of the 80s.

You’re right, Alex isn’t recognised as the genius he was. Alex didn’t talk music: he talked records. He’d started as a cutting engineer in Miami, sorting out the problems producers had created and trying to make the records sound good on vinyl.

Alex knew that, if you made a huge snare sound, something else has to go to make it fit. He learned that stuff the hard way so, when he became a producer, Alex was skilful in choosing sounds that occupy their own space and don’t elbow each other out of the way.

When you started work, did you and Alex bond immediately?

I was a bit nervous of him at first, as he was such a cool guy. But he’d worked with Grace Jones, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Bob Marley – people who had difficult reputations and didn’t give their trust easily, yet Alex was trusted by them all.

Alex was a big part in the conceptual change of the new Thompson Twins identity. Before, I’d write a song thinking there had to be parts in it for both our guitarists to play. Now, it didn’t matter if there were no guitar parts or 50 million of them. We stopped being a band and started designing records.

You were 26 and had been a teacher even before A Product Of… Did having a life before Thompson Twins help you stay grounded when success arrived?

Maybe. But I think the main difference was that I was resolutely sober during the Thompson Twins’ weird escalator ride. I was 21 when I went to India to study yoga. I cleaned up my act then and made a commitment to that lifestyle. It allowed me to see success for what it was, a clarity I might not have had if I’d been partying.

What was the planned progression from Quick Step & Side Kick to Into The Gap?

We moved away from a pure synth sound into a broader musical palette. We’d had to make that purist synth break on Quick Step, but we could relax a bit with our choices on Into The Gap. Our songwriting had matured too. When you have moderate success, you want to change something: make songs more hook-y, for instance. You carry that into your next album.

There are arguments for and against machine-driven music versus organic. On Into The Gap, I allowed other influences in, like earlier records and Talking Heads.

To people who didn’t know your past, Into The Gap should have been your difficult second album. Of course, you’d avoided that by having two albums before Quick Step & Side Kick.

Yes, that’s the smoke and mirrors side of it all. But those first two records were by a different band that I happened to be in. They weren’t led by me in the same way the next albums were.

How much did you enjoy making 12” mixes around this time? The cassette versions of your albums added a lot of remixes.

They were really important. I didn’t realise it at the time, but it was a post-modernist way of saying that there wasn’t one definitive version of our songs. We’d finish making what we hoped was a hit, and then had a chance to say: “Right, let’s turn it upside down and get weird.” It was fascinating to use the studio as an experimental laboratory.

Speaking of alternative versions, is there a lost album of Here’s To Future Days? History suggests you made an alternative version of the album before working with Nile Rodgers.

The version we recorded at Marcadet Studios in France was largely unfinished. We took those initial recordings to New York and overlaid them with Nile, so it’s mostly the same stuff. A couple of songs do have two different versions, from France and New York.

Would you ever work with Alannah or Joe again?

I don’t think Joe is interested. When we split, Joe did some acoustic songwriting, but not much. Joe and Alannah both drifted into other things. Alannah never made another record after we stopped working together. Maybe Alannah thought we’d made a pact to kill off making music altogether. When I drifted back into it, she was disappointed that I hadn’t kept to that pact. My curse is, this is pretty much all I can do. It’s natural for me, and I’m sorry I have to do it.

What did you learn about pop music from your time away before returning to touring in 2014?

A lot of it was technological. In the interim, I no longer needed expensive studios and could write on laptops. I could write in a hotel room or the back of a tourbus. I love that I can lie in bed and write something that might make it onto a finished record.

I’d begun that change with my other projects, The Holiwater Band and International Observer, so it was relatively easy to start writing pop again. Returning to pop was about falling back in love with it, with the challenge of making those sounds.

Until I got on stage again in 2014, I was nervous. But, at the first show, I had a magic moment of realising everything was going to be OK. That’s when I started enjoying pop again.

Did it remain enjoyable while writing your solo album Science Fiction in 2018?

It did. While I was away, I indulged myself in musical projects I hadn’t had time for in Thompson Twins but which was music I deeply loved. International Observer was my dub project and The Holiwater Band expressed my love of Indian classical music. Most people never got to hear them, as they were underground tastes, but I loved them

just as much.

I’d gone underground and had nothing to do with pop for almost 20 years. When I got back in, I felt a bit foolish for forgetting what a challenge making pop music is. It has to be so concise and well-constructed. A pop song has to fit into three minutes, which can be the intro for my other projects.

It can be harder to write pop when you’re older, as there’s something about the innocence of a young band. When you’re older, you know there are 50,000 options while writing a song, so it’s difficult to be concise, but it was interesting to force myself into that discipline again.

Is there a follow-up album on the horizon?

I’m writing songs along those lines again, but I don’t feel it’s the right time to make an album yet. Science Fiction did OK, but that was partly because I’d been touring intensely. If I put an album out now, I’d have to be very prominent again and 2023 looks fairly quiet, as I tend to tour in alternative years. But If I get asked to do a big American tour, maybe I’ll eat my words and make a new album!

It’s been a fascinating life. Have you ever considered writing your autobiography?

It’s tempting to think, “My story is so important,” but I’m not sure it is. I live in New Zealand and agreed with a journalist here that we’d do a book together: not the story of Thompson Twins, but a series of conversations about all sorts of subjects, some of which obviously drifted into my experiences as a musician. But maybe I’m just another guy with some ideas and a bit of luck.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!