Blondie interview: “Everybody we knew was put off by The Eagles and Linda Ronstadt”

By Classic Pop | March 12, 2023

In this interview from 2017, Blondie talked to Classic Pop’s Paul Lester about their 11th studio album, Pollinator

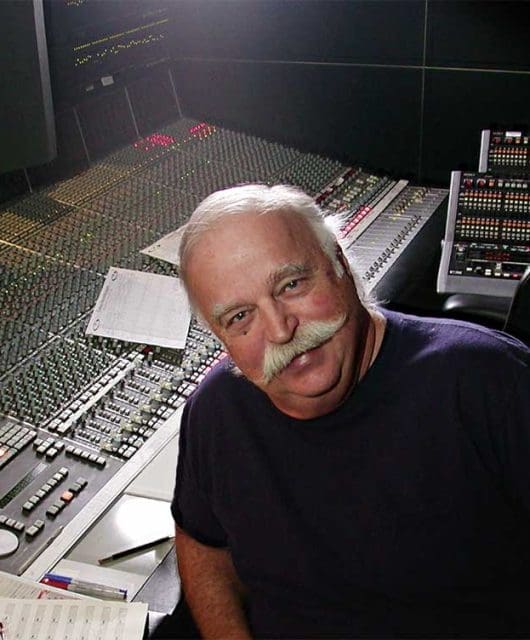

Chris Stein is sitting comfortably, with his legs up on the couch, in a hotel room in Marylebone, West London, as Classic Pop arrives for our interview with the Blondie songwriter and guitarist.

We are up the road from the station where Stein, a keen student of pop history, says The Beatles got mobbed during a scene in the 1964 movie A Hard Day’s Night.

Somewhat jet-lagged, he relates in a laconic Brooklyn drawl, how, at the height of their success, his band experienced their own version of Beatlemania.

“It was round the corner from here, on Kensington High Street,” he says of the moment in September 1978 when Blondiemania hit its peak.

“We did an in-store appearance at Our Price [record shop] and 2,000 kids showed up. The traffic was blocked. That was the first time we saw anything like that. It was a little hectic, getting shoved on to buses, and I don’t know if it would have gotten old after a while, but we were kids and I thought it was great. Despite the crush of humanity, people were respectful.”

This wasn’t actually Stein’s first walk on the wild side. Similar to goddess-like front-creature Debbie Harry, he had some previous.

He might have described himself and his cohorts just now as “kids” but fresh-faced types straight out of a Norman Rockwell painting they were not. No, think of them more as prototypes for the kind of edgy tweens enshrined in a 1990s Larry Clark movie.

Born in 1950, Stein had spent the late-60s mired in America’s counterculture. “I was at Woodstock,” he recalls, nonchalantly.

“It wasn’t as crazy as modern concerts, but it was awesome. Debbie was there, too. Various people that went on to be in the arts, like [‘cyberpunk’ writer] William Gibson, were there.

“I didn’t go to Altamont [the 1969 rock festival where, during a performance by The Rolling Stones, a teenager was killed by Hells Angels] but I had friends who were there.”

Stein witnessed first-hand the hippie dream turn into a nightmare as The Beatles disintegrated, Brian Jones died and Charles Manson ran amok in Los Angeles.

“I went to Haight Street [in San Francisco] in 1967 and ’68 and the difference was extreme,” he remarks. “It got really dark. I saw some weird things in ’68.

“My friends and I were there that summer tripping on Haight Street, walking along in whatever state, and we saw a pickup truck driving down the street and these kids waving in the back.

“And this kid runs alongside it, and they pull him into the truck, where upon they start kicking the shit out of him and pull away. We were like, ‘Did we really see that or were we stoned?’

“There was definitely a darkness going on – there was the Process Church of the Final Judgment in London and all sorts of weird Satanism and strange shit going on in Los Angeles…”

Stein had been dabbling in the black stuff for a while. “I was always interested in magick and the occult,” he admits.

So, too, were other future members of Blondie. Bassist Gary Lachman (formerly Valentine), for example, who is now a world expert on the occult.

When he first met Stein and Harry in New York’s Little Italy, there were books doing the rounds by the likes of Colin Wilson and Aleister Crowley, which led Lachman to become immersed in the culture.

As Stein deadpans today: “We all had similar interests.” He laughs when he tells Classic Pop that he has tried explaining to his teenage daughter that, when he was growing up, instead of going to EDM concerts, he would do things like watch counter-cultural renegades Abbie Hoffman, Allen Ginsberg, the Fugs and others attempt to “exorcise and levitate” the Pentagon in America’s capital.

19th nervous breakdown

If his mind wasn’t blown by that little escapade, his state was altered, almost permanently, by the death of his dad when he was 15, and his subsequent immersion in hallucinogenics.

“My father dying made me a little crazy,” he reflected in 2011. “I wasn’t able to deal with it.”

His experimentation with LSD precipitated a mental breakdown when he was 19, and he was sent to a sanatorium. “It was standard procedure for young people, to do a couple of months in a place like that,” he plays it down now. “I had a lot of friends who had meltdowns. It was partly from hallucinogenics, and partly a delayed pent-up reaction to my father dying.”

Was it like One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest in there? “Nah, that was a glamorous version of it,” he says, smiling indulgently. “It wasn’t that severe, and it was co-educational.”

Not that he needed anywhere to meet females – it wasn’t long before he’d hooked up with Debbie Harry, a former waitress and Playboy Bunny who had been a member of winsome late-60s folkies Wind In The Willows.

By 1973, she was a singer with proto-trash-glam-punk outfit The Stilettos and Stein was their guitarist, and before long they were an item, he mesmerised by her beauty, she by his sulking attitude.

“The Velvet Underground were always a big thing,” he says, explaining his lifelong attraction to the dark side, which said NYC Warhol acolytes captured so brilliantly on their self-titled 1967 debut album.

- Read more: Blondie & Debbie Harry: the complete guide

“I’m always amused that in the middle of flower power there was this record about heroin, death and darkness that all my friends really loved.”

By the early-70s, there had been enough of the right kind of music for a band to come along with the dream of fusing the extremes of it all: the gorgeous commerciality of the 60s girl groups, say, with the punky energy of the original garage rock.

Blondie were that band: equal parts Shangri-La’s and Standells, with a snotty disregard for the status quo.

“Everybody we knew was put off by the Eagles and Linda Ronstadt and all that stuff getting to the top of the charts − all those faceless bands into expertise and musicianship,” he says of this dread era of bland country pabulum and tedious prog virtuosos.

And so in 1974, Stein, Harry and Valentine (replaced in 1978 by Frank Infante), together with drummer Clem Burke and keyboardist Jimmy Destri, became the beautiful postmodern monster that was Blondie.

Soon, they were gigging regularly at premier NYC dives Max’s Kansas City and the legendary CBGB. “We’d go out every night to see bands or to play ourselves,” Stein remembers.

Soon, they were gigging regularly at premier NYC dives Max’s Kansas City and the legendary CBGB. “We’d go out every night to see bands or to play ourselves,” Stein remembers.

“We played CBGB every weekend for seven months at one point. I remember Clem and I realising we hadn’t paid attention to [satirical US television show] Saturday Night Live cos we were never home on a Saturday night.”

At first, Blondie were the runts of the CBGB litter, dismissed as lightweights next to the more serious and/or intellectually rigorous likes of Television, Talking Heads, Ramones, Richard Hell & The Voidoids and The Patti Smith Group, all regular performers at the Bowery club. Soon, there was division – albeit barely perceived – in the ranks.

“There was the artsy camp which was Television, Talking Heads and Patti, and then there was the pop camp, which was us and Ramones,” Stein elucidates. “But really everybody got along. It was a nice fertile period. Towards the end there was a bit of vying for record company attention, but even then it never got really heated.”

Blonde ambition

The idea of Blondie succeeding seemed improbable, just as the band seemed almost too good to be true: the platinum blonde singer and her four brunette sidekicks, all cartoon sass offering an immaculate collage of the ancient and modern. They could have been schemed into being. Not so, according to Stein.

“There was never any grand scheme,” he insists. “It was too crazy. There were all these personalities in the band, ploughing ahead. In fact, there was a lack of focus compared to Ramones or Talking Heads. We were just drawing on a lot of different elements and that became our style.

“There really wasn’t very much pre-planning or strategic meetings, although the guys all liked the suits and ties,” he concedes of their image, as immortalised on the sleeve of third album Parallel Lines (1978, recorded with Mike Chapman, “the George Martin of the piece” as Stein puts it).

There was the icily cool Harry dressed in white, flanked by her black-suited henchmen, the model for every skinny-dude, New York band since.

The boys’ look was the result of a shared love among Stein, Destri et al of mod, the Rat Pack and Sean Connery-era James Bond.

On their 1976 self-titled debut album, from the snarling (Rip Her To Shreds) to the sugar-sweet (In The Flesh), Blondie invented a new paradigm: pop-punk.

- Read more: Top 20 Blondie songs

It made sense that it featured a cameo, on backing vocals, from Ellie Greenwich, co-writer of Be My Baby and Leader Of The Pack.

“She was a hero of ours,” Stein sighs. How about Phil Spector? Were there ever any plans to work with the talented, and tiny, production titan? “He did approach us, but it was at the height of his craziness.

“We went to his house and he came to the door with a bottle of diet Manischewitz in one hand and a gun in the other, doing this WC Fields imitation.

“The house was freezing and he didn’t want anyone to stand up, so we all had to remain seated. He was too weird − a little creepy for Debbie, too.”

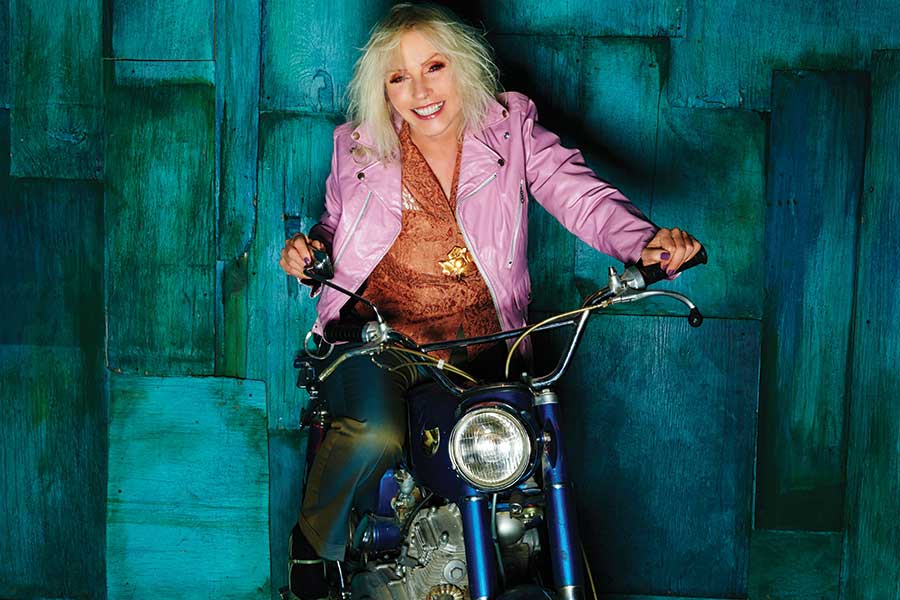

Not that Harry suffered creeps, or fools, gladly.“When Debbie did a promotional tour of the States early on, all the [music] writers didn’t want to be in the room alone with her because of the stigma of punk,” he says, chuckling. “She had that sort of image of the ferocious female.”

Matching Blondie’s new hybrid music was Harry’s gutter-glamour persona. There had never been anyone quite like her. “Janis [Joplin] was always a victim in spite of her power, whereas Debbie was consciously not going in that direction,” Stein the pop historian comments.

“Her referencing of Marilyn [Monroe] and the Hollywood angle of glamour was about empowerment, only divested of any tragic elements.”

Harry had no time for tragedy. By 1978, on the back of several timeless classic pop hits – Denis, (I’m Always Touched By Your) Presence, Dear, Picture This, Hanging On The Telephone – they were one of the biggest bands of the period, eclipsing all the other outfits who emerged during punk or new wave.

In 1979, following the deathless glacial disco of Heart Of Glass, Sunday Girl, Dreaming, Union City Blue and the Parallel Lines and Eat To The Beat albums, they were utterly ubiquitous and omnipresent, on the charts and in the music press, even if the latter were tentative with their praise.

Even as the populace went wild for Blondie, the media were, respectively, cautious of that debut album, savage about the second (1978’s Plastic Letters), lukewarm about Parallel Lines and Eat To The Beat, then critical about 1980’s Autoamerican and merciless regarding 1982’s The Hunter.

Even as the populace went wild for Blondie, the media were, respectively, cautious of that debut album, savage about the second (1978’s Plastic Letters), lukewarm about Parallel Lines and Eat To The Beat, then critical about 1980’s Autoamerican and merciless regarding 1982’s The Hunter.

The latter was their last until 1999’s No Exit, which contained the No.1 hit Maria – arguably the strongest pop comeback in history.

Since then, Blondie have grown in stature, certainly in terms of critical regard, to the extent that their three next albums − 2003’s The Curse Of Blondie, 2011’s Panic Of Girls and 2014’s Ghosts Of Download – were greeted with more excitement than any of the records from their so-called golden age.

Golden years

If anything, with their brand new album, Pollinator, Blondie are more highly regarded than ever.

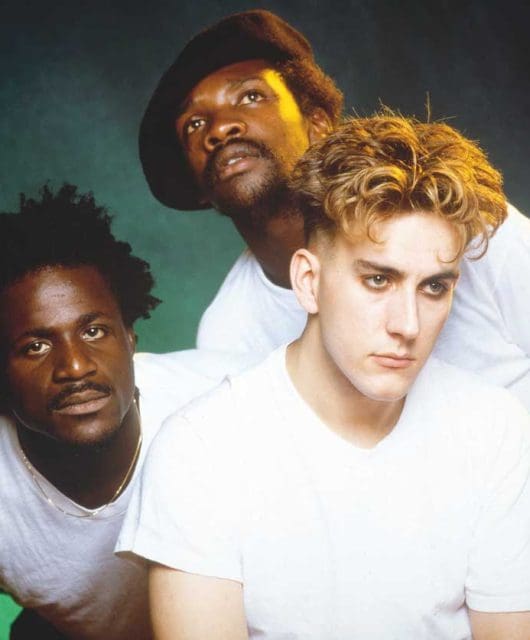

This is perhaps why pop’s great and good – Charli XCX, Johnny Marr, Sia, Nick Valensi from The Strokes, Dev Hynes, Dave Sitek of TV On the Radio, Joan Jett and Laurie Anderson – rushed to collaborate with Stein and Harry (plus faithful drummer Clem and relative new boys Leigh Foxx on bass, Matt Katz-Bohen on keyboards and Tommy Kessler on guitar).

Everyone loves Blondie. “Well,” shrugs Stein, who reveals he “wound up getting pretty fucked up in the 80s and 90s but now I don’t drink anymore. We try to be smart about what we’re doing. You have to work towards your deficiencies and know what you’re capable of.”

On Pollinator, their 11th studio album, they used The Magic Shop in Manhattan, and were the last band to record in the studio, which recently closed due to exorbitant rental costs.

Blondie, who may have started off parodying the ephemerality of pop but have become the enduring stars of their – incidentally groundbreaking and world-changing – scene.

“If we have one more No.1, we’ll be the only band to have No.1 hits in four decades − at the moment we’re tied with The Bee Gees with three decades,” Stein says with some pride.

Their place in the pantheon is assured. Indeed, it seems that the only people Stein needs to convince of Blondie’s greatness are his two daughters.

“Oh, they take it for granted,” he says, miffed that his girls’ friends are more impressed. “They’re like, ‘Woah, your dad…’”

Not that impressed, though. “No,” he says, somewhat glumly. “It would be a bigger deal if I was Justin Bieber. And they don’t even like Bieber.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

- Read more: Blondie – Pollinator album review