Saint Etienne interview: “I certainly wouldn’t be embarrassed if someone called us a 90s band”

By Classic Pop | February 20, 2023

With their melancholic disco singles and album statements, Saint Etienne were one of the most underrated bands of the 90s. We spoke to them in 2017 as they released their ninth LP, Home Counties… By Paul Lester

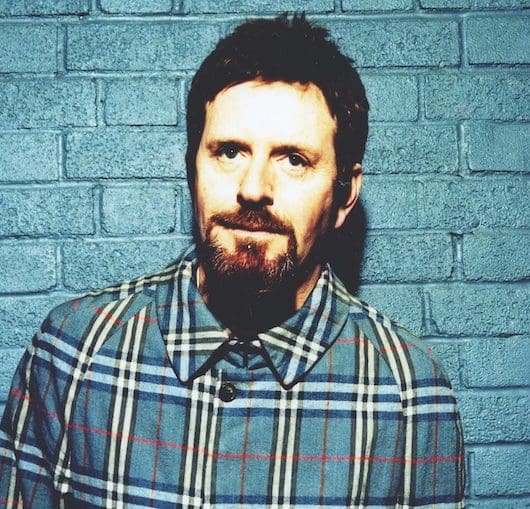

With their mash-up of Swinging Sixties imagery and melodies with modern technology and electronic beats, Saint Etienne – Bob Stanley, Pete Wiggs and Sarah Cracknell – were an emblematic 90s outfit.

In a way, they kickstarted that decade with their 1990 debut single, a dubby, housed-up version of Neil Young’s Only Love Can Break Your Heart that caught the baggy, rave-era mood of “aciid”-tinged euphoria.

It was a time of anything-goes mixing and matching: in Manchester, The Stone Roses were busy allying Byrdsian bliss-pop with danceable grooves and Happy Mondays were turning scuffed indie and funk into one scabrous cocktail while down south Primal Scream were proving that you could incorporate elements of krautrock, The Beach Boys, country and Lee “Scratch” Perry, often within a single song.

Saint Etienne were avatars of this “record collection rock”, evincing a dizzying array of influences. But although Stanley might joke that, like the militant quasi-anthem by Denim – the early-90s neo-bubblegum outfit fronted by Lawrence (Hayward), formerly of Creation indie rockers Felt – he was “against the 80s”, Saint Etienne didn’t dismiss the era out of hand.

For starters, ABC’s state-of-the-art Northern soul and Brill Building-inflected post-disco was an obvious precursor, and he and Wiggs would regularly namecheck Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark’s Dazzle Ships as a key release in their idiosyncratic personal pantheon.

They also acknowledged Pet Shop Boys as pioneers of their kind of emotionally engaging, melancholy dancefloor entreaties.

Of course, they would never have worked as a synth duo like PSBs, Yazoo or Blancmange because neither of them could sing.

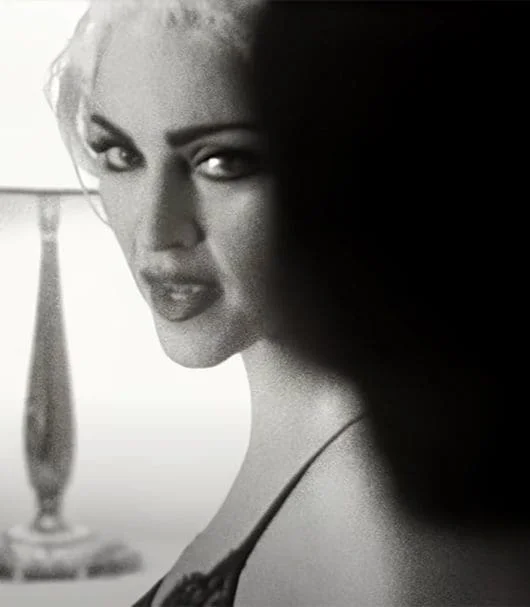

Luckily, these avowed non-musicians with more ideas than instrumental prowess had as their secret weapon the divine Ms Cracknell, whose breathy voice alluded to all manner of 60s French pop and girl groups and gave Saint Etienne that extra dimension.

These backroom boys with their latterday Julie Christie (Cracknell’s actress mother had been a pretty, blonde mainstay of 60s British TV) on the mic were somehow, simultaneously, lo-fi London-philes (their earliest recordings were done in producer Ian Catt’s bedroom studio in Pollards Hill, near Mitcham) and Euro-glamorous, with a hi-tech sheen.

They had one foot in mid-80s “cutie”/C86 indie culture (indeed, Croydon boys Stanley and Wiggs had their own fanzine, Caff) but they also loved Chicago house and Detroit techno.

An intoxicating melange

Their genius was to bring all of these disparate elements together.

On their 1991 debut album Foxbase Alpha and attendant singles Kiss And Make Up and Nothing Can Stop Us, they were equal parts Screamadelica and Sarah Records: imagine The Field Mice in Ibiza, undercut by a fin-de-siecle sadness.

“One of the things that inspired me was when Martin Fry said, ‘ABC are going to soundtrack the 80s’,” recalls Stanley. While the other two are interviewed in person, he’s on the phone from Saltair, an artistic community in Yorkshire where he lives with his wife and young son (although he still has a home in North London).

“Talk about condemning yourself not to live up to your hyperbole! But we went in the studio in January 1990 [to record Only Love…] to try and do just that.”

He chuckles at the audacity, even insanity, of it all. Actually, they had a five-year plan, because of the David Bowie song, and because that was generally how long bands lasted.

He wonders whether, notwithstanding the plundering from so many places and periods, and despite the eight albums they have made since – up to and including 2017’s typically wonderful Home Counties – ultimately Saint Etienne are now regarded as a 90s band.

“I certainly wouldn’t be embarrassed if someone called us a 90s band, which we get quite a lot,” avers Stanley, who prior to forming the group with Wiggs worked as a freelance music journalist for Melody Maker. “It doesn’t bother me cos we did a lot in the 90s, and there was a lot of good music.”

He pauses to compile a mental list, one with a possibly ironic flourish – you never know with the deadpan, prodigiously pop-omnivorous Stanley (his 2013 book Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story Of Modern Pop truly covered every aspect of the music).

“The KLF, The Prodigy, Pet Shop Boys, um, Whigfield…” He certainly “never wanted to be one of those groups, like Mari Wilson or The Maisonettes, who obviously wanted to live in a previous decade”.

“It felt like the 80s had ended a good two years before [1990],” he continues. “Acid house felt like the beginning of a new decade – that’s what we were born from. When I think of the 80s I think of 1980-’82, not the dire stuff at the end of the decade like Go West or Then Jericho. We were definitely Against The 80s in that sense.

“But we were obviously inspired by C86 aesthetically – cos of the DIY aspect and cos me and Pete wrote that fanzine. But we always loved pop music and the fact that, at the beginning of the 90s, the charts were suddenly populated by outsiders and lunatics like The KLF, who were the biggest band in the country for a year, which was mind-blowing, and is hard to see happening again.

“Also, back then, you could buy keyboards for 100 quid from Loot, which is how we started. We did Foxbase Alpha on budget equipment at Ian Catt’s studio in his bedroom at his mum and dad’s house, with a reel-to-reel tape recorder – this was before DAT and memory sticks. It was all very DIY, cheap and cheerful. But somehow, you could get into the Top 40.”

In fact, Saint Etienne got into the Top 40 no fewer than 14 times between 1990 and 2005, the year of their last high chart entry. How many records do they think they’ve sold in total? Millions?

“I would have thought so,” says Cracknell, ever a vision of English loveliness – she and a fashionably bearded Wiggs meet Classic Pop in a North London cafe (well, of course they do), travelling from their homes, respectively, in Oxfordshire and near Brighton. “We used to sell quite a lot of records back in the 90s. We’ve got a couple of 100,000-selling Gold albums and a couple of Silvers.”

Were they the proverbial Big In Japan? “Momentarily.” Wiggs laughs at the memory of being chased down the street in Tokyo by fans on a school outing, although, ever self-deprecating, he believes it was more likely the teachers than the pupils doing the screaming.

Hitting the heights

Saint Etienne had their biggest hits with 1992’s Join Our Club, 1993’s You’re In A Bad Way and Hobart Paving, 1994’s Pale Movie, 1995’s He’s On The Phone and 1998’s Sylvie and The Bad Photographer.

They initially used Beats International’s 1990 No.1 hit Dub Be Good To Me as the model for what could be achieved with a dextrous blend of melody and beat science, and ended up, if not soundtracking the 90s, producing music that kept up with technological advances while remaining somehow timeless.

They were peers of those other 60s-referencing pop house types Deee-Lite and Betty Boo, southern counterparts of esoteric Mancunians World Of Twist and Intastella, and in the same ballpark as experimental electronicists The High Llamas and Stereolab.

But they were regulars on Top Of The Pops and had, in the early days, Oasis and Pulp supporting them – the video for Pulp’s Babies was filmed in the north London flat shared by Stanley and Wiggs – even if they were never really part of the Britpop party.

Wiggs – currently studying in his spare time for a postgraduate degree in Film Scoring (in 2014 he wrote and performed the music for the movie Year 7) – remembers the early days of Saint Etienne, when he and Stanley would dabble with “rudimentary melodies” with facilitator Catt and “somehow cobble together” songs, with ideas of samples in their heads.

They were probably at a similar level of non-proficiency as The Human League. “None of us were good enough to sit down with a guitar and piano and ‘jam’,” as Stanley puts it.

In a way, at that point, they were a virtual band, a studio chimera – “an experiment, really,” decides Wiggs. The intention at first was to bring in different female singers to front each release: Moira Lambert sang on Only Love… while Donna Savage was vocalist on follow-up single Kiss And Make Up.

Being a fully-functioning performing unit wasn’t really on the cards until Cracknell joined. A drama student from Windsor, she had been in an indie band called The Worried Parachutes before moving to London at 17.

She had stints with other acts, but following her vocal on third Saint Etienne single Nothing Can Stop Us she became a full-time member. She, too, recalls their untutored early days (“scattergun” is how she describes their approach), and admits that, in terms of prowess, they have improved immeasurably in the quarter-century since.

“We’re a lot better now,” she laughs, ordering a hot chocolate as Wiggs settles for a cider.

According to Stanley, their musical ability – or lack of same – didn’t hinder their ambition.

“We actually thought Only Love… could do something. And then Dub Be Good To Me went to No.1 and [the danced-up cover of] Strawberry Fields Forever by Candy Flip reached No.3 and we thought, ‘There you go!’ It didn’t seem that unlikely, although at the same time it did seem a bit ridiculous cos we were always following our muse with lots of in-jokes and references to things,” he adds of the snippets of dialogue and strange ambient interludes on Foxbase Alpha and 1993’s follow-up, So Tough, inspired by arcane Dexys Midnight Runners album tracks and Teardrop Explodes B-sides.

Like The Smiths, they created their own self-contained universe, with their own idiosyncratic iconography. “We were cocky,” says Stanley, “but also quite odd.”

So cocky, in fact, that in one of the last articles he wrote for Melody Maker – a piece on the new wave of post-Roses/Mondays wannabes such as Northside and Flowered Up – he sneaked in a mention of Saint Etienne.

“I thought, ‘Let’s see what happens’. And the labels got in touch! It was incredibly cheeky, but it worked.”

Highway to heavenly

Saint Etienne signed to Heavenly and took their “shared love of minor chords and dance music” to the toppermost of the poppermost, or at least to Top Of The Pops where, for their first appearance (for You’re In A Bad Way), they shared the Borehamwood stage with East 17 (Stanley remembers Brian Harvey playing pool at the bar with “Mandy from EastEnders”, Nicola Stapleton), 2 Unlimited and Rolf Harris doing Stairway To Heaven.

“Our first time on is embedded in my mind,” Stanley says. “It was amazing. The whole place had that British Rail gravy smell that you didn’t get anywhere anymore. It was trapped in time – like being in a sitcom in the 70s.

“I was a wooden model of myself onstage – I barely moved – but it felt like, ‘That’s it.’ It was like playing in the cup final at Wembley. It was always going to be a pinnacle of my life, and I was quite aware of that as it was going on.”

Being on TOTP strongly hinted to Wiggs that his decision to jack in his job in “phone support” wasn’t as hasty as he first thought. Then, one day during a picnic in Highbury Fields, someone approached him for an autograph, and that confirmed it.

“It was like I’d staged it,” he laughs, still amazed. “It was really bizarre – like, I’ve done the right thing here.”

For Cracknell, the moment of realisation – that Saint Etienne had truly become a mainstream proposition – came during their performance on the main stage at Glastonbury in 1994.

“When we walked out to 30,000 people,” she sighs at the memory. “We got there really late, and didn’t have enough time to take it on board. I didn’t presume tons of people would come and watch us, so it was a real, ‘Wow!’ moment.

“I’ve watched footage of it and I look like the cat who got the cream,” she says, although Wiggs admits he was so overwhelmed by the occasion, he was petrified into total stasis.

Sounds of the city

Their first three albums – Foxbase Alpha, So Tough and 1994’s Tiger Bay – were all recorded in London and are considered by Stanley to be of a piece. For the excellent, and overlooked, Good Humor (1998) the band decamped to Sweden to work with Cardigans producer Tore Johansson.

It was their bid to shake off their reputation as the quintessential Londoners – they even gave “humor” an American spelling.

“We all got a flat in Malmö for that one,” Stanley reminisces. “It was terrific – I have incredibly fond memories of living and eating together, like The Beatles in Help!

“That,” he explains, “was the first album where we all wrote together as well – for the first three, me and Pete wrote together and Sarah wrote separately. That’s how we’ve always worked since.”

Stanley sees Good Humor and the subsequent two albums – 2000’s Sound Of Water (recorded in Berlin, with arrangements by To Rococo Rot and Sean O’Hagan) and 2002’s Finisterre – as another obvious grouping, and the start of “another era” for the band.

And he would put the next three – 2005’s Tales From Turnpike House, 2012’s Words And Music and the new Home Counties – together.

The latter is a “pretty loose” (Wiggs’ words) concept about the commuter belt that manages to make such unfashionable subject matter engaging by populating the songs with colourful characters (such as the Church Pew Furniture Restorer and the Train Drivers In Eyeliner), and filling the songs with elegantly hummable melodies.

Stanley might be a fan of rock’s cult heroes or marginal eccentrics, whose trajectories were marked by vertiginous highs and subterranean lows, but his group have never gone off the rails.

Did they never have a mad moment, when fame went to their heads? “There was a time,” mutters Wiggs over the thump of Personal Jesus on the cafe stereo, “when we went a bit nuts, and if we’d carried on that way we might have ended up…”

“…very ill,” Cracknell finishes his sentence.

When asked why their friends in Pulp became so successful while Saint Etienne maintained a steady, modest path, they ascribe it to Pulp’s amazing live form and the fact that, as Cracknell says, “They were absolutely ready for it”.

And because Saint Etienne didn’t release an album for four years, they were never really lumped in with the Britpop massive, even if Oasis did support them in Glasgow and Birmingham, where Wiggs remembers them being

“full-on rock’n’roll”.

Unlike many of their peers, who shone brightly then faded away, Saint Etienne are in it for the long haul. All the better for pop scholars to study them over the distance.

The sleevenotes that accompanied their albums by the likes of Jon Savage and Simon Reynolds, and their reclaiming of the capital as a psychogeographic space (London Belongs To Me, indeed), have afforded Saint Etienne a brainy allure.

And yet they did have proper hits – even one, 7 Ways To Love, in 1991 as Cola Boy – that proved they had “the common touch”. But are they really more of a theorist’s delight, making conceptual pop music for academic types?

“I don’t think we hide our light under a bushel,” says Stanley of the suggestion they’re bookish and far from the degenerate rocker stereotype, adding that he “would love to cultivate a mystique”. Fact is, none of them have ever suffered a meltdown.

“I read this interview with Justin Hayward [of The Moody Blues] where he said: ‘Acid? I took it 10 or 11 times, then I realised that’s probably enough.’ So sensible! We were probably like that. We all took drugs and did things we shouldn’t have looking back, but we were very sensible. Very Home Counties.”

Home Counties is out on Heavenly Recordings

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!