The Lowdown – The Police

By Classic Pop | March 25, 2015

Given the anti-establishment ethos that fuelled the punk movement in the late Seventies, it’s remarkable that the big breakout act from that scene was a new-wave trio fronted by a former schoolteacher.

The Police were formed in 1977 when erstwhile schoolteacher Gordon Sumner – or Sting, as he became known due to his wasp-like, yellow and black sweater – met Stewart Copeland in a London jazz club and, discovering they shared a mutual excitement for the burgeoning punk scene, formed a band.

Along with a third member, Henry Padovani, they began playing pub gigs and one night caught the eye of Mike Howlett, who invited them to join his band, Strontium 90. The union lasted a few months until, realising the group weren’t going anywhere, bassist Sting and drummer Copeland quit, took guitarist Andy Summers with them and continued as a trio.

The band began to write and record songs with little attention until Copeland’s brother, Miles, heard a Sting composition called Roxanne. Sensing it would be a hit, he borrowed £1,500 for them to record their songs professionally, became their manager and secured them a deal with A&M Records.

The world lapped it up and the following four years were a whirlwind of successes, with over 50 million albums sold, huge tours and numerous awards. However, the gruelling schedule took its toll on the band. The breakdown of Sting’s marriage was the catalyst for much of 1983’s Synchronicity, their biggest album and also their last in the studio.

Things were also strained between the group members by that point – so much so that they recorded their parts in separate rooms. They split up soon after.

In 2007, The Police reunited for a 15-month tour to mark their 30th anniversary – the third biggest-grossing tour of all time. It mended relationships within the group, leaving the door open for further collaborations. “Who knows?” Stewart Copeland said at the time.

The must-have albums

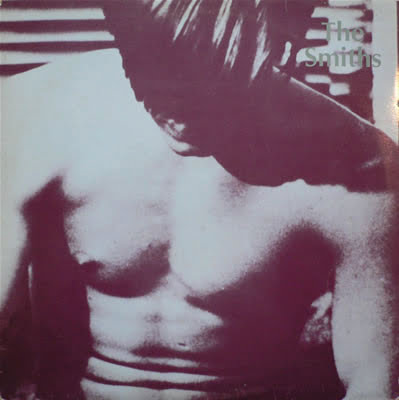

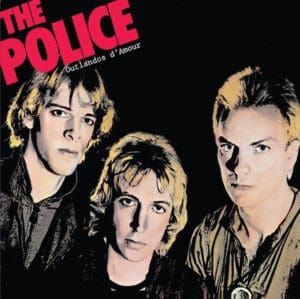

Outlandos D’Amour 1978

The debut album, recorded on a shoestring budget

Although Outlandos d’Amour – the band’s debut long-player – offered teasing glimpses of influences and musicianship way beyond the punk/New Wave scene from which Sting and co had emerged, its creation couldn’t have been more faithful to punk’s DIY ethos.

Translating as “outlaws of love”, the album was recorded on a budget of just £1,500, with the initial sessions laid down on secondhand tape in a doctor’s home studio soundproofed with egg boxes.

The sparse production allowed the group’s strengths to shine through – specifically, their knack for wrapping irresistible pop hooks in straight-up rock and Caribbean rhythms, which resulted in a distinctive, winning sound that was entirely their own.

All three of the album’s singles, Roxanne, Can’t Stand Losing You and So Lonely, reached the UK Top 20 (only Roxanne charted in the US, at number 32), despite the controversial lyrical content that radically limited their radio airplay (prostitution, suicide and loneliness respectively). Meanwhile, cuts such as Truth Hits Everybody, Peanuts and Next To You paved the way for what was to follow.

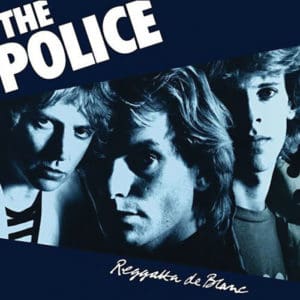

Regatta De Blanc 1979

A New Confidence emerged – and spawned the band’s first Grammy

If Outlandos d’Amour had been the sound of a band finding their feet, Reggatta de Blanc (while reggatta is a made-up word, the title loosely refers to the trio’s “white reggae” sound) was the moment when The Police ultimately clicked as a group. Written and recorded in three weeks, the album saw them expand their musical language and embrace their experimental side, the reggae rhythms allowing their different styles of drumming, guitar and bass to fuse together majestically.

Opening with the classic Message In A Bottle, the album’s highlights were plentiful. Walking On The Moon, The Bed’s Too Big Without You, Deathwish and Bring On The Night are among the best songs The Police ever recorded, while the instrumental title track won them their first Grammy.

The album was the band’s first to hit the UK number-one spot, and they never looked back – all three of their subsequent studio albums did the same. It also produced their first two UK number-one singles – Message In A Bottle and Walking On The Moon. Both Sting and Stewart Copeland have gone on record saying it’s their favourite Police album.

Ghost In The Machine 1981

Darker and more experimental but still full of classic Police tunes

By the time they were due to record Ghost In The Machine (named after the Arthur Koestler novel), The Police were keen to radically overhaul their sound, feeling that if they were tired of it, their fans would be too.

Leaving Surrey Sound Studios for the first time, they headed to the Caribbean and incorporated synthesisers and saxophone into their material to give a more richly textured sound (as heard on Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic). The resulting album – their fourth – was much more experimental than previous efforts, and certainly a lot darker, reflecting where the band were emotionally at the time.

Despite their problems, Sting, Copeland and Summers managed to produce some of their best work – Spirits In The Material World and Invisible Sun (the latter dealing with the conflict in Northern Ireland) were deservedly big hits, while Summers’ Omegaman had the potential to be until Sting blocked its release as a single, much to the fury of the guitarist, who says the move made him feel “like a backing singer”.

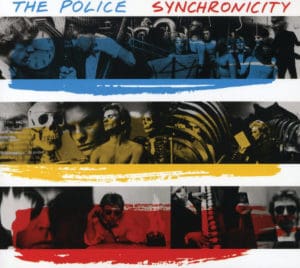

Synchronicity 1983

The trio’s final – and most successful – studio album

With sales of over 13 million copies, Synchronicity was the album that cemented The Police’s position as one of the biggest bands in the world. The campaign was launched with the soft-rock juggernaut Every Breath You Take and went on to produce further hits in Wrapped Around Your Finger, Synchronicity II and King Of Pain, with album cuts such as Tea In The Sahara showing that Sting’s songwriting was at its zenith.

Ironically, the album that provided their commercial peak was written and recorded in circumstances of abject misery. The breakdown of Sting’s marriage to actress Frances Tomelty informed some of his most visceral lyrics, while the relationship between him, Copeland and Summers was so bad that they recorded their instruments in separate rooms and were photographed individually for the cover.

The album pushed them creatively and personally to their limits. Onstage in front of 70,000 fans at New York City’s Shea Stadium, Sting decided he’d reached “Everest” and, realising The Police couldn’t get any bigger, disbanded the group.

The must-watch videos

Every Breath You Take

“I trusted them completely because they’d been musicians,” says Sting. “I handed it over to them and let them do what they wanted.”

Shot on an LA soundstage, the stark video was an antidote to the Technicolor travesties that the early video age produced. “It was based on old films of 1940s jazz clubs,” explains Godley. “We shot in black and white with noir-ish shadows to create a smoky atmosphere, and it worked extremely well. We didn’t make them do crazy performances or anything; it was simple and worked for the song.”

Wrapped Around Your Finger

“We decided we’d have Sting dancing and leaping around, and stretching himself as a performer,” says Kevin Godley. “But because the video combined slow-motion action with real-time vocals, we had to playback at double the speed and he had to run around and mime at double the speed – it sounded like Mickey Mouse!

We were trying to capture the graceful feel of the song, while what was happening on set was the opposite. We had no idea if it would work because it had never been done before.”

Synchronicity II

A post-apocalyptic wasteground set the scene for the futuristic clip, with the band perched on 25ft-high platforms as giant piles of debris – car parts, guitars, drums, wires and papers – swirled about them.

Needless to say, with such an ambitious project, the shoot didn’t go smoothly. “The set caught fire,” recalls Kevin Godley. “Litter and hot lights – not a totally safe combo!” The (literally) overblown video set a precedent for the increasingly big-budget videos that would follow during the decade – most notably Duran Duran’s The Wild Boys.