Alison Moyet interview

By Classic Pop | July 1, 2021

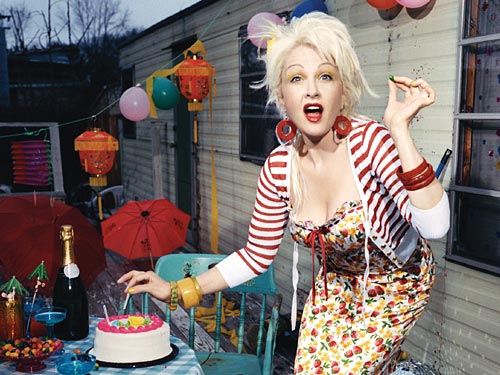

In this Alison Moyet interview from 2017, the former Yazoo singer talks to Wyndham Wallace about surviving 35 years in the pop business…

It’s mid-April, and Alison Moyet is cradling a phone in the kitchen of her terraced Brighton home – the one she swapped for a seven-bedroom house and garden four years ago, the one without off-street parking – as words to her latest album’s title track are read back to her admiringly.

“Some people we don’t mean to lose,” the lyrics declare, “They snag on branches and separate in market squares…”

“I can’t begin to tell you,” she interrupts, her pleasure almost palpable, “how much it means to me that you’ve engaged with the lyrics. It’s more important to me than singing, than whether I have a voice or not. You just made me really happy by quoting that to me. How brilliant it is to actually be a writer, to be a poet, rather than just to be a mainstream pop singer. Thank you!”

The gratitude is unnecessary. Moyet’s latest, astonishing album, Other, is arguably her most realised collection to date, and its strengths lie as much in its vivid, inventive language as in its dark, startling music.

Brimfull of her trademark vocal intensity and peppered with striking imagery – I Germinate’s “bats in a blink eclipse the moon/ Like whipped kerchiefs in a courtly swoon”, The Rarest Birds’ “dove-grey gum constellations” – it represents the culmination of her slow but steady reinvention from ‘pop singer’ to ‘proper artist’.

To some, Moyet remains fossilised as the Essex girl who first emerged as one half of Yazoo, alongside Vince Clarke, before her 1984 solo debut, Alf, took her to No.1, going four-times platinum in the process.

Even when, in 2014, BBC Breakfast summarised her career ahead of an interview, they stopped at 1986’s Is This Love?, as though the seven albums she’d made since – including 2002’s Hometime and 2004’s Voice, which both went gold, and The Minutes, which had recently gone Top 5 – were mere afterthoughts.

Her six-month run in a successful West End musical, and the play, Smaller, in which she’d starred alongside Dawn French, were also overlooked.

But Moyet’s been steadily refining her craft, often out of the spotlight, and though her commercial profile may not be as high as it once was, she’s now free to make music that appeals, first and foremost, to her rather than the marketplace. The signs are that it’s winning her new fans.

“I’ve been frustrated,” she admits when reminded of that BBC appearance, and of people’s nostalgia for her early work, “but less so now, because I think people are finally catching up with me. I’ve been fortunate that I’ve been successful, and it was because of that success that later on I was able to make choices that were perceived risky. What frustrates me is the assumption that your best work is always going to be your bestselling, so you’re locked into this particular time. I hated my 20s. I really like middle age and I’m comfortable with the person I’ve become. My great successes aren’t related to my big sales.”

Though she describes herself, knowingly, as “plump with confidence”, she’s also thoughtful and appealingly – if unnecessarily – self-deprecating, though this she disputes. “It’s not even self-deprecating. I try to answer honestly, and I think maybe you’ve got to have lots of self-confidence to own your crapness.”

Moyet’s delight, however, comes from the fact that Other is as much a celebration of her love of language as her self-declared, perennial outsider status. It feels different from previous releases, she says, “because the emphasis on it is not singing. The emphasis on it is words, and I’ve been coming closer to that point all the time.”

This is particularly surprising, she confesses, because she barely reads. “The most impactful of times with books in my life was nursery rhymes,” she comments, pausing briefly before adding, “and I’m not even saying that wryly! I don’t read, and when I do read, I read fantasy.”

Indeed, one song, The English U – in which she describes herself facetiously as “a criminal to grammar/ To apostrophe, the hammer”, but nonetheless “pretty sound with tenses/ With ‘when’ and ‘which’ and ‘whence’s” – is a tender paean to her late mother’s love of prose. “Even though she sunk into Alzheimer’s,” Moyet explains, “the last vestige of anything she had was her knowledge of grammar.

“The disappointment she had in me being dyslexic and not being able to spell… How I wished I could have honoured her. But language has become very important to me. I love words, I love the shape of words, and the colour and the sound of them.”

Her mother, one might confidently suggest, would have been proud of what she’s achieved, and not just because of her verbal wit.

Other finds Moyet embracing what once troubled her, whether it be her self-confessed public awkwardness – “I’m so prone to circular thinking! I can forget where I’ve been, and yet one word that I’ve said could keep me awake for days!” – or her concerns about how best to proceed with her work. If, as she said at the time, The Minutes was “mindless of industry mores that apply to middle-aged women”, she’s gone even further with Other.

“It’s mindless of all the industry mores” she emphasises. “I’m aware of the damning attitudes towards middle-aged women: the idea that we’re asinine, or we’re occupied by gentler pursuits, or that middle-aged women aren’t expected to be creative, or be seen in the media.

Read our Album By Album feature on Alison Moyet

Top 10 Vince Clarke remixes

“You can either react by feeling like you can’t push yourself forward, or you just continue regardless of how you’re going to be accepted. I make records with no expectations now. I don’t expect to be on the radio, I don’t expect magazines to want to cover it. I just expect at this point in my career to make a record that I want to make.”

Attaining this has been harder than one might expect for someone who’s sold well over 20 million albums. Other – as its title suggests – addresses the manner in which she’s always felt like she didn’t belong.

Born to a French father, whom she describes fondly but bluntly as “a complete and utter control freak”, and an English mother, “who was a quite oppressed woman”, she grew up in what she describes as “quite a violent environment”, and always found communication intimidating, spending her early years mentally translating French so as to be able to speak English.

“Without sounding crap,” she elaborates, “I have always felt ‘other’. I came from a bit of a peasant family, where everything you had you had to make. Before I was in Yazoo I didn’t even have a cassette player.”

Moyet had other reasons to feel different, too.

“Weird things have happened in my life that have made me think about the fact I have always for some reason drawn unkindness,” she says, albeit without a note of self-pity. “In latter years, a lot of people have been very faithful to me, and very loving, and full of goodwill, but right down to my very first experience in hospital as an eight-year-old, waking up crying from a tonsil operation and having the nurse put her face next to mine and say ‘Why don’t you shut your mouth?!’ These little things have happened at such an alarming rate. Like when I asked to audition for the school musical, and the head of English said, ‘What would we want someone like you for?’

“All these things when I was young, I felt, ‘Yeah, why would you want someone like me?’ It didn’t even seem unreasonable after a while. It just seemed like, ‘Yeah, fair play. I know that I don’t fit.’ And when you’re younger, not fitting in is crushing.” She hesitates momentarily. “Actually, I’ve now come to that place where I feel quite blessed by it.”

Even once she was a star, her well-documented weight problems drew attention away from her music, and she recalls an occasion when a French journalist asked: “Don’t you feel ashamed going on stage looking the way you do?” Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that she withdrew from the public eye.

This was partially due to disagreements with her label, Sony, following the release of 1994’s Essex, but in 2014, on Desert Island Discs, she revealed she’d also suffered for many years from agoraphobia, provoked by a painful encounter with Elvis Costello when, instead of praising a show, as she’d intended, she blurted out “You dragged that out a bit, didn’t you?”

Read our Pop Art: Vince Clarke feature

Read more: Top 40 80s debut albums

In recent years, fortunately, she’s coaxed herself out of the house, and not only to tour. Though formal education never suited her, she’s started to study figurative sculpture. “I left school pretty much unqualified,” she says. “I didn’t even have an English exam. What I always wanted to do was art, but I had no qualifications.”

Nowadays, she travels by train to college, and speaks enthusiastically about piece mould castings and modelling in clay. “I’ve got one guy in my class I call Diligent Dan. He’s fantastic. He’s one of those people who will work really carefully at everything. But that’s not who I am. I could make a really fantastic model and then fuck it all up by being really slapdash. I did this portrait which I thought was fantastic, but completely fucked it when I moulded it.”

In the past, this might have stopped Moyet sleeping, but though her inability to focus continues to dog her, her new hobby has brought her peace.

“The thing I like about art the most is you can occupy yourself however many hours, and it’s the only time my brain isn’t whirring about anything else. I can lose the circular thinking, the concern I have constantly that I’ve said the wrong thing or behaved in the wrong way.”

Quite apart from informing her new album, her personal difficulties have also made her especially sympathetic to others who struggle to conform. An ambassador for Diversity Role Models, her love of Brighton is enhanced by its inclusivity, and one song, The Rarest Birds, was inspired by living in a place where “none of us have to be scared about who we are. They might kick our fucking teeth in, but they can kick our teeth in and we’re going to go out singing.”

It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that she’s also active on Twitter, whose 140-character rule suits her self-proclaimed inarticulacy.

“People say, ‘Let the trolls go’, and I say, ‘You’ve got no idea’. I have this battle desire, and I love it when people think they can floor me with words that don’t touch me. A couple of songs have been informed by that on the album,” she continues, pointing especially to Beautiful Gun. “Being contacted by Americans who are both completely right wing and hate anything liberal, and yet would practically weep if you discussed taking away their guns. You’re frightening people smaller than yourself, and yet you have to have this accoutrement to do it.”

She also talks angrily of “people who put words in a deity’s mouth and claim him for their own, and yet there’s nothing Christian about the way they behave other than their church attendance.” She points to other hypocrisies, too, such as those who are “anti-abortion, pro-life, and yet really anti-social care. When does this child go from ‘Their life must be preserved’ to ‘Their lives may be damned’? Is it when their adult teeth come through?”

Alongside the freedom she now feels to express herself and defend others, Moyet’s also taken severe measures to liberate herself from her past. When she moved house, she threw out huge mountains of historical baggage.

“I just trashed everything I had: the stuff in my loft, my gold discs, all my itineraries, everything that I kept pointlessly. I have no care to carry things. I have no care to carry that success. All of those things that you keep and buy, that make note of the fact you existed: when do you ever look at them? When does it touch your life? When do you need them?”

Evidently these extreme decisions have paid off. Other celebrates Moyet’s individuality in an unexpectedly vibrant fashion, as well as the fresh lease of life that her newfound self-assurance has brought her.

“I’ll tell you how normal my life is,” she chuckles. “I came back from sculpture the other day on the train, and I looked bad. I’m covered in plaster, my hair hasn’t been brushed. I was sitting at a table of four people, and there’s a smartly dressed young woman, sitting diagonally to me, who pushed over her bag of nuts and said, ‘Would you like these?’ That will explain to you how invisible I’ve become: she thought I was a bag lady! I feel so bad now. I should have taken her nuts and thanked her for my one meal of the day. I never ever felt I looked underfed!”

Thirty-five years, almost to the day, since Yazoo battled their way to No.2 with Only You, Alison Moyet seems finally to have found not only herself, but also a refreshed muse.

“What I love now,” she concludes, “is the freedom of not being noticed so I can actually now observe, as opposed to spending my whole time worrying I’m being observed. Maybe that’s where creativity for me comes from now: I can actually be a person in society, which is what I wanted to be, and yet invisible. I still feel ill equipped. I still feel like a different beast. However, where once I would very much have liked not to have been, now I have no desire for it to be otherwise.”

Vive la différence!

Alison Moyet’s website

Read more: Making Duran Duran’s Rio