His productions are some of the defining moments from the last four decades of pop which launched – and relaunched – the careers of some of our most treasured artists. In 2018, producer Stephen Hague took Classic Pop through an extraordinary career behind the studio desk… By Andy Jones

Stephen Hague is one of the finest record producers of modern times. If you didn’t know that, you’ll almost certainly agree after we tell you about just a smattering of his productions, many of which came at pivotal points of the artist’s careers, serving as launchpads (or ‘re-launchpads’, if there is such a word), to fame, fortune and notoriety.

There’s West End Girls, the track that ultimately gave us Pet Shop Boys; there’s Freedom, the first solo single produced for Robbie Williams. Then there’s World In Motion, the song that gave us – and continues to give us – so much hope every time England enter a football tournament.

Hague’s vision gave us some classic moments in 80s music, but he’s continued to work throughout the 90s and beyond with diverse artists including Tom Jones, Blur, Manic Street Preachers, James, Peter Gabriel, a-ha, and on and on.

For someone who has helped create the sound of British pop music over the last four decades, you might be surprised to learn that Stephen was born and raised in the States, but he always had an eye and an ear on this side of the pond.

“From a very early age, I couldn’t get enough of the stuff I was hearing on the radio,” he recalls, “especially British bands, though I had my American favourites as well. By the time I hit junior high school, things were already getting tribal: American surf vs British pop and rock, and I was in the Brit tribe.

“I was around for the birth of the long-playing album as an ‘artform’, and the rise of FM underground radio in the States – a great time to be soaking all that up, first generation.”

At 17, Hague dropped out of high school and moved to LA, like so many others “chasing fame, fortune and girls, not necessarily in that order” – but unlike many that make the move out West, his journey to success started almost immediately.

“I made some friends, played keyboards and bass in cover bands,” he explains, “and then stumbled into a circle of drinking buddies that included some Fleetwood Mac insiders. One of them was Walter Egan. He had just gotten signed, and Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks produced his first album.

“I joined his band and played on the record. There was a hit [Magnet And Steel], and we went on tour, opening for big acts all over the States.”

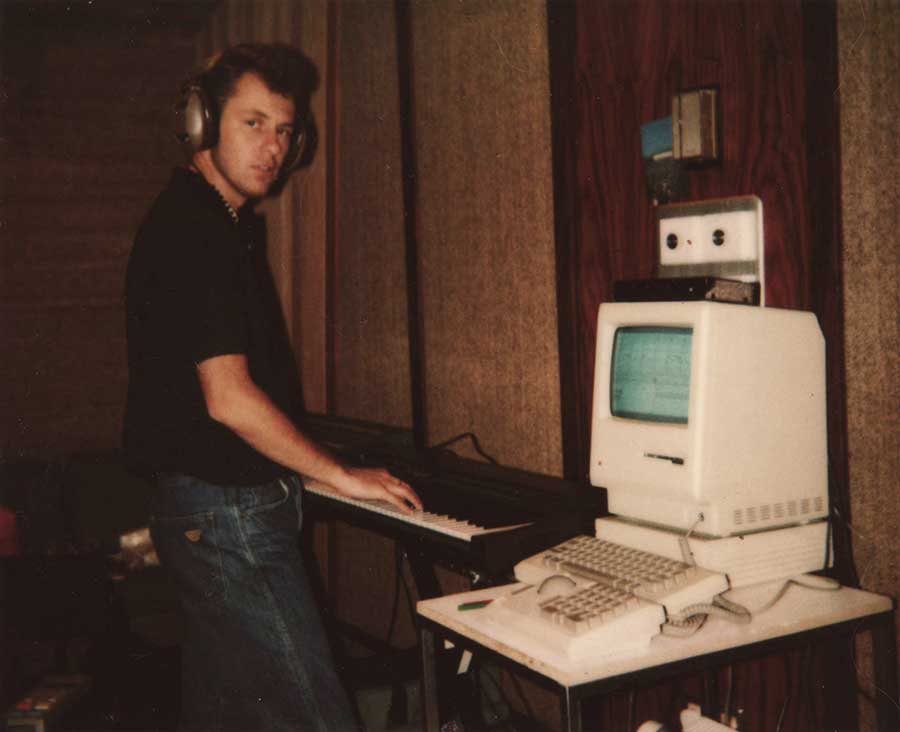

Hague used the money he made to purchase some recording gear, a couple of four-track tape machines “and the basics for a home studio, which barely existed at the time”, and set up shop in a garage under the apartment he was renting. He then co-founded the band Jules And The Polar Bears with singer-songwriter Jules Shear, who’d go on to pen hits for The Bangles, Cyndi Lauper and Alison Moyet.

“We got signed to Columbia Records and I co-produced three Polar Bears albums with Jules,” Hague says and adds with a wry smile: “We were loved by the critics, and largely ignored by the public.”

However, one positive outcome of being in the band was that Hague was able to afford to buy a Yamaha CS-80, now widely regarded as the best synthesiser of all time (and worth at least five figures if you can find one, synth-fact fans).

“It was one of only three in LA at the time,” Stephen recalls, “and once word got around, I was approached by Michael Omartian, a top-flight session keyboardist, who asked if I would join in on some of his work and program the CS-80.

“For the next year or so, we worked together on everything from Dolly Parton to The Pointer Sisters to Gordon Lightfoot, on records produced by Richard Perry, Peter Asher, Waronker and Titelman, and many more. “Being on all those sessions was like going to producer school, and being paid for it. It was an invaluable experience.”

Suddenly, I’m a producer!

Hague found some local LA success with Gleaming Spires (the backing band for Sparks, with whom he struck up a friendship), but his big production break came after a tour, again with The Polar Bears, opening for Peter Gabriel on his first US outing after leaving Genesis.

“Peter and I hit it off and stayed in touch,” says Stephen. “I sent him some of my home-recording projects, he liked them and pitched me to his record company, Charisma. I had moved back to Boston by that time, and was scrambling for work.

“One day, I got a call from Charisma asking if I’d like to go to New York to write for and produce The Rock Steady Crew; fallout from Malcolm McLaren’s Duck Rock album, which he did with Trevor Horn.

“I did it [Hague produced the single (Hey You) The Rock Steady Crew], and it went Top 10 in the UK. Then the next call from Charisma was to do something with Malcolm himself. He came to Boston, rambling on about ‘opera meets hip-hop’, and we wrote and recorded Madam Butterfly. It was a hit, too.

“On the back of that I was approached by OMD and worked on their Crush album, then the call from the newly formed Pet Shop Boys, and suddenly, I’m a producer! Life is strange.

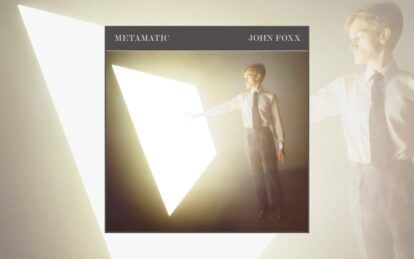

Producer Stephen Hague was a pioneer of digital recording techniques; his re-recording of Pet Shop Boys’ West End Girls was a No.1 single on both sides of the Atlantic

“That OMD album was the first major release that I was the solo producer on,” he continues, “so that was an important step, plus I loved the band and making the record, but the penny really dropped with West End Girls. Although it was done as a one-off at the time, I remember listening to a rough mix and thinking, ‘This is really fucking good!’

“When it hit No.1 in the UK, though, it seemed like something had gone wrong with the charts. I couldn’t believe it. That was the first time I realised I really could do this, and producing became my full-time focus. I was lucky, though, that ‘success’ arrived as I was turning 30, and I’d acquired some skills and cleaned myself up a bit. If it had happened when I was 25, I would have fucked it up, I’m certain of that.”

An electronic legacy

After West End Girls, Stephen suddenly had multiple record companies and bands approaching him, hoping for some Hague-style magic dust. He claims not to have had a particular sound back then, but his work with Pet Shop Boys and OMD undoubtedly linked him to the synth-pop side of the 80s, and he does admit a hefty contribution to the genre.

“I loved electronic music from quite early on,” he says, “Morton Subotnick, Tomita, Larry Fast’s Synergy records and then Kraftwerk, of course. My background had been guitar, bass, and piano, but I was an early adopter of synths. British synth-pop started to become its own category: I suppose I share some of the blame for that!

“When you have success with a certain ‘sound’, the projects offered tend to reflect that, style-wise, and you can miss out on other kinds of acts. Late in the 80s, though, I found a balance between synth-pop and more guitar-based stuff, and that gave me more flexibility.”

Stephen eventually succumbed to temptation and in 1985, he moved to the UK, where he enjoyed most of his success. Throughout the rest of that decade, he produced more Pet Shop Boys highlights (including What Have I Done To Deserve This? and It’s A Sin), another album for OMD (The Pacific Age) and sealed something of a synth-pop hat-trick with The Innocents album for Erasure.

“It was a big change for me to go to work every day and be almost certain that the records would actually be heard,” he says. “I was in the studio almost non-stop, and having that momentum was exhilarating, although 12 cups of black coffee a day took its toll on my sleeping habits. But I’m a fairly upbeat guy by nature, and I was having a blast. A big plus was the quality of people I had the chance to work with.”

But not every project led to long-term friendships… “Well, sooner or later your luck runs out!” Hague smiles. “There were a few chemistry mismatches here and there, which doesn’t mean the records suffered for it necessarily. I don’t want to name names, but there was one album in particular where I was no longer on speaking terms with one half of a well-known duo by the end of the project, and his name wasn’t Andy Bell.

“And there were a few times I had to ban certain record-company guys from the studio, for the greater good! Looking back, maybe I should’ve done that a bit more often.”

Career highlights

Hague has now worked with an incredible roster of artists, including Robbie Williams, Tom Jones, Peter Gabriel, The Pretenders and Blur. So which have been the highlights?

“I realise now that it is quite a list!” Stephen says when presented with his own CV, explaining: “I’ve always been one to keep moving and rarely revisit the past, but I could break it down into a couple of categories. One would be having the chance to work with people I grew up admiring.

“It’s hard to describe the feeling of opening the studio door and Dusty Springfield walks in, for instance, or having been hugely influenced by an artist like Todd Rundgren and then making records with them.

“It’s just crazy and a little intimidating. I guess it separates the men from the boys when you can look Robbie Robertson in the eye and say: ‘I don’t think you’ve nailed the chorus yet’ – just surreal. It was a similar experience with Chrissie Hynde, who I adore. And Tom Jones? Well, who didn’t grow up with that voice on the radio?

“But I’ve found that even with the most ‘iconic’ singers, you hit a point where you’re just two working musicians in the work environment, and you find your common language and get down to the task at hand.

“Then there are artists that aren’t carrying much career baggage, or smaller suitcases, anyway,” Stephen says. “When I first met Robbie Williams, he pulled up to RAK Studios on a bicycle, having just pedalled over from Maida Vale. His record company had set us up. The mission was to make his first solo single, and have it enter the charts at No.1.

“I was right in the middle of a James album, and could only carve out a few days. It all worked for the most part, except it only got to No.2, and it felt strangely like I’d let everyone down. He’s a good guy, Robbie, I like him a lot.”

And while he’s proud of his extensive back catalogue of hits, Hague still finds it hard to define a great record.

“Everyone, from the guy in the corner shop to Quincy Jones, has an idea of what a great record is, and I’m constantly cross-referencing what I’m working on with records that I’ve heard and loved (or hated), and the favourites I grew up with. Everything that goes in resurfaces eventually, hopefully at the right time!”

- Read more: Top 40 80s debut albums

- Read more: Top 40 Vince Clarke songs

Playing for ‘En-ger-land’

Stephen recounts an extraordinary few days which gave us the (other) ultimate football song, World In Motion…

“There was a group of fans waiting outside the studio waiting for the England team; the word had gotten out. The players were in surprisingly good spirits and someone arranged for ‘refreshments’.

By the time they made it into the studio, each player had a bottle of Champagne and a few beers. Keith Allen appeared with a raft of lyrics and a major hangover, and on his heels came Tony Wilson and Bernard Sumner. Peter Hook arrived and was mingling with the footballers. Everyone was either very under-slept, hungover, or in the process of getting drunk. We had to get things moving fast.

“My plan was for each player to do part of the infamous rap. We started with Gazza. Nope. Then the rest had a go and it was shocking. I can neither rap nor play centre-forward at Wembley, so I couldn’t get frustrated, but my plan wasn’t working. Then John Barnes gave it a try and we had our guy.

“Keith, Tony and I discussed the original ‘E is for England’ line. I thought it was a bad idea to have a drug reference and face a possible BBC ban, so that went. In that same chat, ‘England’ became a three-syllable word, resulting in the ‘En-ger-land’ chant on the outro.

“The next day, we began the process of making the actual record. I thought it should have an instrumental section, so headed off to look for some voiceover stuff. I knew fuck all about English football then, but brought back a couple of videos of England’s World Cup glory. We tried a few things and it seemed to work. I left London for LA the day after we finished, so wasn’t in the UK when it hit No.1, but every four years, it rears its head again, and what a strange beast it is.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.