Jesus Jones – keeping up with the Jonses

By Classic Pop | February 9, 2023

Jesus Jones’ sampladelica indie-dance was one of the sounds of the early 90s. Via hits such as Real Real Real and Right Here, Right Now, they charted high on both sides of the Atlantic. In 2018, with a new album then imminent, we talked to them about success and excess, megalomania and dinosaur-dwarves… By Paul Lester

Jesus Jones were one of the biggest bands of the early-90s, their mash-up of indie and dance, rock energy and sampling technology giving them several hits including Right Here, Right Now, International Bright Young Thing, Real Real Real and The Devil You Know – not just in this country but in the US as well.

They were part of a vanguard of indie rock bands – arguably started by B.A.D. and continued by The Shamen, Pop Will Eat Itself, That Petrol Emotion, Carter USM and others – who used systems and techniques normally associated with techno or house, even hip-hop, to enliven the alternative guitar music scene.

“Age Of Chance were a band I really noticed,” says Jesus Jones mainman Mike Edwards, from his home in Dartmoor, of the Leeds crossover dance-rock act who topped the UK indie chart in 1986 and almost broke into the mainstream a year later with their mutant disco remake of Prince’s Kiss.

“The Shamen were another band who really made it click: putting out quite traditional songs and playing live alongside electronic stuff.”

Was Edwards aware of the previous generation of groups incorporating dance (funk) elements in their sound: the early-80s likes of A Certain Ratio, Stimulin, Funkapolitan and 23 Skidoo?

“They didn’t really feature in my musical development,” he says, “but, of course, there had been bands bringing rock and dance together – New Order are a classic example. But those [aforementioned] groups meeting disco with rock didn’t inspire me. No, it was hip-hop’s integration with rock that captured my imagination.”

And it all began 30 years ago, on a beach in Torrevieja, on Spain’s Costa Blanca.

Sitting there bored and directionless, Edwards (vocals, guitars, keyboards) and Simon “Gen” Matthews (drums, sequencers) – old school friends from Bradford on Avon in Wiltshire – together with new recruits Alan Doughty (bass), Iain Baker (keyboards, programming) and Jerry De Borg (guitars, backing vocals), decided to form a band.

They had already, in various permutations, been in outfits such as Camouflage and Big Colour.

“They were part of the evolution,” Mike Edwards explains. “Both featured Gen and Alan and they were vehicles for trying new ideas out. But it all crystallised with the addition of Iain on keyboards and us becoming Jesus Jones.”

The look was to be pure skate-punk (Edwards was into skateboarding and Baker worked in a skateboard shop). As for their name, that came to them as they sat on that beach, a bunch of pasty, skinny Jones boys surrounded by sun-kissed hunks called Jesus.

“It was something like that,” says Edwards, who to sustain himself during the early days did a variety of menial jobs including builder’s labourer. “Jerry has claimed he came up with the name, but I’ve always insisted it was me. It was more about alliteration than anything else, and a slight risquéness. It just sounded right.”

It has long been part of Jesus Jones lore that on that Torrevieja holiday Edwards made a pact with his bandmates: that it would either be his way or the highway. Did he really insist on total control?

“Words to that effect,” he replies. “I’d been messing around with a tiny sampler, a drum machine and a four-track tape recorder. I thought, ‘I’ve got the ideas, I know how to do this…’ I saw how rock bands were presented. We just need to be very focused. I said, ‘Let me do it my way. I’m sure it could work.’”

Bright young things

Info Freako (1989) was the first we got to hear of Jesus Jones.

Described by defunct music weekly Sounds as “a sticky, sneering slice of megalomania” and compared favourably by the NME to such noise epics as The Beatles’ Helter Skelter, The Jesus & Mary Chain’s Upside Down, The Dead Kennedys’ Holiday In Cambodia and Public Enemy’s Bring The Noise, Info Freako was a riot of guitars, beats, samples and sneers.

It reached No.42, a sign of Jesus Jones’ arrival as a serious pop force, mere months after signing to Food Records.

“We’d just signed our contract in December 1988 and were playing The Rock Garden in Covent Garden to six people,” Edwards recalls. “Within two months, we were playing places that had lines all round the block.

“All it took was a couple of articles [in the music press] and all the tastemakers – the ‘early adopters’, as techies would call them – wanted to check us out.”

Jesus Jones’ emergence coincided with that of The Stone Roses, Happy Mondays et al – the so-called indie-dance/baggy/Madchester brigade. Not that they wanted to join any scene.

“I got annoyed at any suggestion that we would be fitted into a scene,” Edwards snarls. “It used to grate like mad that we got called ‘grebo’,” he adds of the micro-movement featuring PWEI and Gaye Bikers On Acid and their messed-up mangle of punk and techno.

Nevertheless, Jesus Jones benefited from being in the right place, at the right time, earning acres of feverish acclaim from music journalists ever eager to find the latest international bright young things.

“We got written up as being something revolutionary, so a lot of people wanted to jump on that bandwagon,” Edwards says. He was eminently capable, however, of matching the hype with outrageous claims of his own. “It was the state of the art,” he says, justifying his motormouth tendencies and quasi-messianic fervour.

“That was the game you played. The Stone Roses’ whole approach was, ‘We are the greatest thing ever.’ It seemed you had to say something fairly outrageous, however unsubstantiated, to make any headway in the music press.” Did he start to feel like Jesus? “Not in the slightest – I was never that daft.”

He remembers their subversive assault on the mainstream. “We got played on Bruno Brookes’ drive-time slot on Radio 1, and it seemed pretty incongruous at the time – Info Freako at 5:10pm on a Tuesday!”

With a mile-wide competitive streak, Edwards became “insanely jealous” when Birdland, a band of blond pretty-boys briefly touted as future heroes, reached No.35 in the charts while Info Freako, and follow-ups Never Enough and Bring It On Down, all stalled just outside the Top 40.

Still, this was an exciting time, marked by the release in October 1989 of debut album Liquidizer, which reached No.31 and was rapturously received in some quarters of the press.

“It felt as though all your dreams were coming true,” he says, although Never Enough had been inspired by the opening scene in Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories, in which the protagonist finds himself dismally dissatisfied with

his lot.

The acid tests

For now, though, it was all smiles – literally, as acid house swept the nation and the Berlin Wall came tumbling down, part of a global tide of optimism.

Jesus Jones superbly captured this good-times mood on their 1990 singles, Real Real Real (No.19), Right Here, Right Now (No.31) and International Bright Young Thing (No.7).

“Yeah,” Edwards nods. “They were the zeitgeist songs for ‘glasnost’. Right Here, Right Now was saying, ‘It’s a good time to be alive.’”

So good, in fact, that they got invited on to Cannon and Ball’s Casino television show, a surreal incursion that saw Jesus Jones performing Info Freako “to a bunch of bemused pensioners” on ITV. Thrillingly seditious stuff, although it was hardly reflected by their tawdry, humdrum living arrangements.

“We were still living in horrible little flats in London, so nothing much in our lives had changed except our day jobs were really exciting,” he says. His exhilaration was tempered by an undercurrent of discontent.

“It looked like there was a future and I felt convinced we were making the right sounds, but being very ambitious I was disappointed the album only got to No.31. It had nothing like the impact I thought it should have in my arrogant way.”

Indeed, second album Doubt – which reached No.1 in January 1991 – was written largely in a state of doubt. “When we started getting proper pop success, that’s when I got disillusioned by it all,” Edwards admits. “I felt [success] was devalued by the process; the selling-your-soul element. I started to lose my passion for being involved in music.”

Edwards can recall the exact moment ennui set in. “I was sitting in a Radio 1 studio for the Top 40 show. They brought us in because they knew we had a decent chart position for International Bright Young Thing.

“I remember Mark Goodier looking over at us as though we were going to be really happy, and the immediate response in my mind was, ‘That’s it. We’re just New Kids On The Block now.’ Instead of being happy I thought we’d become what we detested.

“I felt like the rug had been pulled from under me. We’d gone from Info Freako and being this revolutionary new band offering something exciting, to just being part of the pop machine.”

Did he make friends with any other stars of the period?

“I was very pally with Seal for a while,” he says. “I met him at an awards show and we got on really well. He’d come to the odd party at my house. Then one year he said, ‘I’m off to do the second Live Aid concert, then I’m off to Los Angeles – I’ll give you a call when I get back.” Edwards pauses, feigning devastation. “I’m still waiting for the call, Seal!”

Keeping it real real real

The success of Doubt allowed Jesus Jones to move out of their “horrible little flats”, to more salubrious parts of the capital. But fame hardly went to Edwards’ head.

Rather, for all his conceit, he had about him a vaguely abstemious air. Not for him limos and debauchery – no, he was too worried about the impact on his voice.

So he’d ride everywhere on two wheels, partly to avoid “arseholes on the Tube who’d sing your songs at you”; he even started competing in mountain bike events, simultaneous to his pop success.

“I tended to be very clean-living on tour,” he reveals. “I was terrified of losing my voice onstage. So yeah, I was very abstemious.

“I was always so blinking busy, songwriting. There didn’t seem to be any spare time, and any that I did have I spent getting massively into cycling and competing in mountain bike events. I was never cut out to be the archetypal rock star.”

Yet by 1991, Mike Edwards – who, to all intents and purposes, was Jesus Jones – was the toppermost of the poppermost. “I would say that from January 1991 to summer 1992, we were really riding high,” he agrees.

“Our album was No.1 ahead of Sting and Alexander O’Neal, and despite my doubts about the pop machine, we played the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury, performed to a quarter of a million people in Brazil and, in the summer of 1992, supported INXS around Europe and at Wembley Stadium in front of 72,000 people.

“I started getting into the mindset that if wanted to maintain that success I had to behave with megalomaniacal swagger.

“We started to tour the US playing in 800-capacity clubs and by the end of the tour there would be more people than that outside trying to get in. It was absolutely amazing.

“Every band wants to be big in America but really only us and EMF did it at the time. The NME would say The Stone Roses were the only band worth taking seriously, and I’d think, ‘Yeah, but we’re Top 5 in the States’.

“Their adoration of fame can be slightly odd. Groupies would be very forward. You’d have a security guard come to the door and say, ‘I’ve got a girl outside who says she wants to blow the band. Shall I let her in?’

“There was another incident where a woman had blagged her way backstage and jokingly the security guard said: ‘Give me your underwear.’ The next thing I know he’s holding her knickers. It was pretty extreme.”

Once step beyond

The examples Edwards cites of peak JJ madness were the time one of their crew dangled a member of the band from a hotel window, and the occasion they were invited to mime a song for an Argentinian TV show, surrounded by women in bikinis and dwarves dressed as dinosaurs.

The performance ended up with guitarist De Borg wrestling on the ground with one of said dinosaur-dwarves.

“It took so much to mime that song knowing that was going on behind you,” Edwards laughs. “That was one of the most focused performances I ever gave.”

Third album Perverse (1993) was Jesus Jones’ last hit LP (No.6) and saw Edwards reaffirm his love of electronic dance at a time when the rest of the alternative world was embracing grunge.

“I felt fairly sure our career was on the wane at that point,” he says now. “But I was quite defiant because music was making massive strides forwards: I was going to techno clubs anything up to seven nights a week and hearing music that I found really inspiring and thrilling.

“I’m very proud of Perverse. I think it’s our best, most ambitious album. We took a leap out into the bold.”

By fourth album, Already (No.161, 1997), Edwards “knew the game was up – and so did the record company”.

“They were looking for the sure-fire hit, and there is no sure-fire hit,” he observes. “They’d invested very heavily so we had to do the album twice effectively, and we spent six months in the studio. It’s an album I’m proud of, but it was made in very difficult circumstances.”

Its aggressive electronic dance sound chimed with the “big beat”/techno-rock then being made by The Chemical Brothers and The Prodigy.

In a way, Jesus Jones pre-empted them both; even creating the space for them to succeed. Jesus Jones made one more album (2001’s London) “for the hell of it”, after which they’d play a show “every so often” with The Wonderstuff or other like-minds from indie’s golden age.

Wake up from history

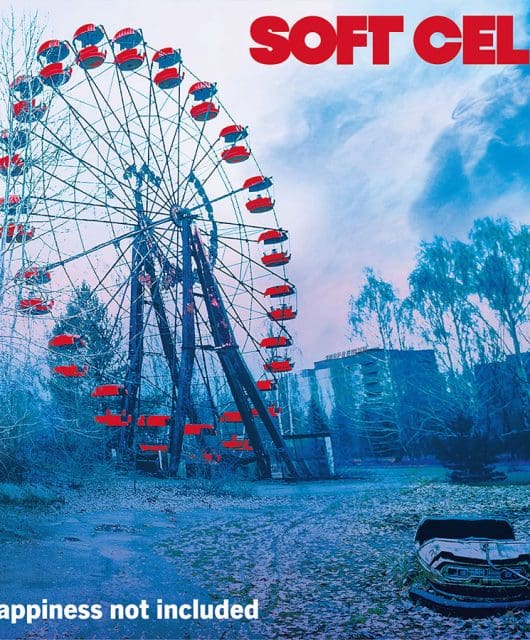

Now Jesus Jones are back with all original members intact, and a sixth album, Passages, which hits record stores on October 27.

It’s a back-to-the-future job, with all the fun-filled techno-rock you could want, and titles such as Suck It Up and How’s This Even Going Down that capture the snotty attitude of yore, even if it’s tempered by hard-won wisdom and experience.

“We’re all in our 50s now so I can’t write with massive self-belief anymore,” says Edwards, a married father-of-three, who has suffered personal losses of late.

“There are more interesting things to write about, like the people close to my age and younger who’ve died recently. So there are lots of things on the album about having come this far and looking at the way life and your self-image change.

“So much pop music now is brave and exciting – much better than it was in the mid-90s. However, a band playing a good song live is still a great thing to witness.”

Jesus Jones started out under the influence of rap and rock acts, but ended up exerting quite an influence themselves. “It was interesting talking to Liam Howlett in 1993, because he remixed a song from Perverse,” Edwards says.

“He was fed up being in the rave scene and working with a rock band it was apparent that that was a way to engineer that – and soon after they became a rock entity. The Prodigy might not have had the same success had we not suggested one possible alternative direction.

“Jesus Jones and bands of our ilk readily accepted that you can mix electronic/digital music with live music, whereas when we started it was quite divisive. Our success was part of making that accepted.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!