Classic Album: Gary Numan – The Pleasure Principle

By Felix Rowe | March 16, 2023

Gary Numan goes solo and pre-empts the sound of the next decade with a No.1 record that remains a compelling document of its time and continues to inspire great pop music today – The Pleasure Principle… By Felix Rowe

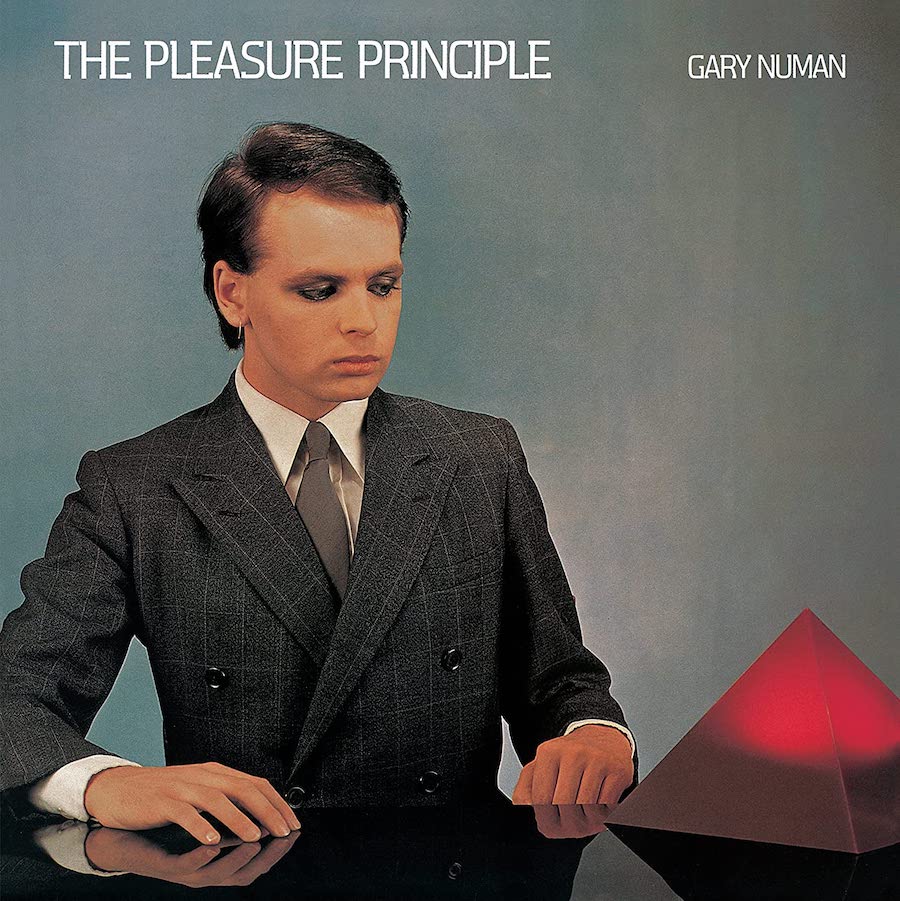

It’s an enduring image: a young, besuited man behind a desk, fixated on the throbbing red glow of a translucent pyramid object. His face, while almost expressionless, nonetheless carries a degree of reticence and suspicion at the mysterious, futuristic form before him.

But clearly he’s curious, too, enthralled by its untapped potential. Like a portal into another dimension, the future has literally manifested itself before his eyes, and it’s his for the taking.

This is, of course, the iconic imagery that adorns the front cover of Gary Numan’s debut solo record, The Pleasure Principle.

Over 40 years later, we now know just how prescient it turned out to be. Numan seized that metaphorical prism with both hands and used it to help shape the future of pop.

The Pleasure Principle is the centrepiece of three UK No.1 studio albums in succession – his extremely successful ‘Machine’ phase, that spawned two chart-topping singles and continues to resonate today.

Its influence has spread far and wide, extending beyond pure pop into hip-hop, dance, reggae and even industrial metal.

Pick any of the countless ‘Best of 80s Pop’ compilations at random, and there’s a good chance that it features either Cars or its predecessor Are ‘Friends’ Electric?

After all, both are so completely representative of the 80s – in sound and aesthetic – despite actually belonging to the previous decade.

Although by no means the only pioneer of UK synth-pop, or indeed even the first, Numan was certainly positioned on the cutting edge, operating at the advance guard of electro-pop.

- Read more: The Lowdown – Gary Numan

When he first arrived on the Old Grey Whistle Test and Top Of The Pops, he did so fully formed – like an android beamed down from space, sent on a mission to teach us earthlings how to groove.

In fact, the reality was not quite so clear cut. Numan’s early man-machine persona owes as much to accident as it does to design. Like many synth-pop heroes, Numan’s musical journey began on six strings, delivering scrappy three-chord punk.

Tubeway Army’s debut single That’s Too Bad has more in common with Buzzcocks than Kraftwerk. The band were signed off the back of the punk explosion a good year or so before they even discovered synths.

They stumbled upon them (almost literally) in the studio while recording their eponymous 1978 debut album.

While that record documents their first dabblings in the dark arts of electronics, it essentially remained a more conventional band effort.

Equally, the androgenous, robotic cyborg look – somewhere between the crisp, clinical and ordered Kraftwerk and Bowie’s Thin White Duke – was, at least partially, another happy accident.

Numan has since admitted its genesis was a matter of pragmatism, when the BBC’s make-up department slapped on a load of white foundation and eyeliner to hide his acne shortly before a Top Of The Pops appearance.

Likewise, his cold, detached performances that became key to the android persona he attributed to stage fright and incompetence.

Props to Numan for candidly shattering the mystique behind his own mythology. Still, however he arrived at it, he certainly nurtured the image to great effect.

The pleasure is all mine

Although now billed as a solo artist, the personnel on The Pleasure Principle remains essentially the same as on the previous Tubeway Army album.

Recorded swiftly, the LP was released in September 1979, less than six months after the band’s last effort, Replicas, with the core line-up retained.

In fact, Numan had wanted to ditch the name as early as the first Tubeway record, distancing himself from the punk scene the band grew out of.

Gary had long been the face and creative driving force of the band, not just writing the songs, but also producing their records.

The latter is a considerable and under-recognised feat for an unproven kid, still barely out of his teens. It was only off the success of Replicas that his label, Beggars Banquet, consented to the new identity.

The Pleasure Principle picks up directly where Replicas left off, indulging Numan’s obsession with the dystopian stories of sci-fi futurist writers like JG Ballard and Philip K. Dick.

He’d already explored these themes right off the bat with Tubeway Army, back when he was known as Valerian, though by now the music was keeping pace with the futurist stylings.

Replicas was heavily inspired by Dick’s book, Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?, the same source material for the Ridley Scott classic, Blade Runner (incidentally Numan’s favourite film).

With The Pleasure Principle, the album’s title and cover were direct references to the painting of the same name by Belgian surrealist artist, René Magritte.

Even song titles play into the notably sparse and clinical imagery – single words thrown out like a typological list of theoretical concepts or constructs of modernity: Cars, Films, Tracks, and so on.

While the record is frequently hailed for its sonic invention, in reality it uses a very limited palette of sounds, derived from a standardised core ‘band’ set-up.

- Read more: Gary Numan interview

Throughout, you’ll witness the same identifiable synth sound (innovatively pushed through guitar pedals), crunchy live drums courtesy of Cedric Sharpley and bass from Paul Gardiner, then a few otherworldly textures on top.

Despite the progressive choice of instruments, it’s still essentially conforming to convention: a band playing together live in a room, rather an electronic producer, painstakingly programming beats and samples in an automated studio environment.

The looseness and – dare we say – punk mentality is still discernibly present. A notable hangover, of course, is Numan’s vocal itself.

Possessed of a limited range, he’s not a naturally gifted singer. Nonetheless, he uses what he’s got to great effect, firing out his words in his childlike twang like the Artful Dodger lost in the wrong century.

Equally potent, is the inclusion of violin or viola, courtesy of Chris Payne and Ultravox’s Billy Currie, that provide a counterpoint to the synthesized sounds, and an otherworldly character when overlaid.

As with the best synth-pop, it’s that tussle between the machines and more organic elements that create its unique character.

The era was captured in a performance at Hammersmith Apollo in the month of release (September 1979) – later issued as the live album, Living Ornaments ‘79, and (with a slightly different tracklisting) The Touring Principle.

It largely draws on tracks from The Pleasure Principle, bolstered with a smattering from the first two Tubeway records, which again emphasise his punkier beginnings.

The stage production and lighting draw on the futuristic aesthetic, two large risers flanking the drummer and triangular tube lighting evoking the album cover.

A lasting pleasure

While his ‘Machine’ period was a commercial peak, the huge success of The Pleasure Principle meant Numan spent the next decade or so seeking to escape its shadow.

Speaking on BBC 5 Live in 2018, Gary reflected: “Becoming successful seemed so much easier than staying successful – that was really hard! And then the other problem is when you’ve been around a long time, there’s a whole stigma attached… It’s impossible to portray yourself as being current, really, because no-one’s going to believe it.”

Gary’s ultimate low point, by his own admission, was 1992’s funk-pop influenced Machine + Soul, which – though by no means bad – he would describe as his most ‘un-Numan’ record.

It was the catalyst for ‘correction’, ushering in the darker, industrial sound that has characterised his later career; rougher round the edges and loaded with swagger.

This coincided with the rise of industrial electro-rock acts from Marilyn Manson to Nine Inch Nails referencing his early work.

A punky, hard-edged version of Cars performed live with the latter in London in 2009, highlights his affiliation with US alt-rock.

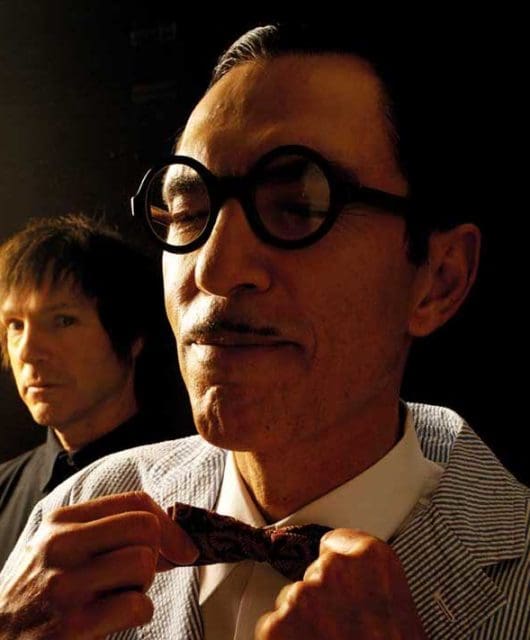

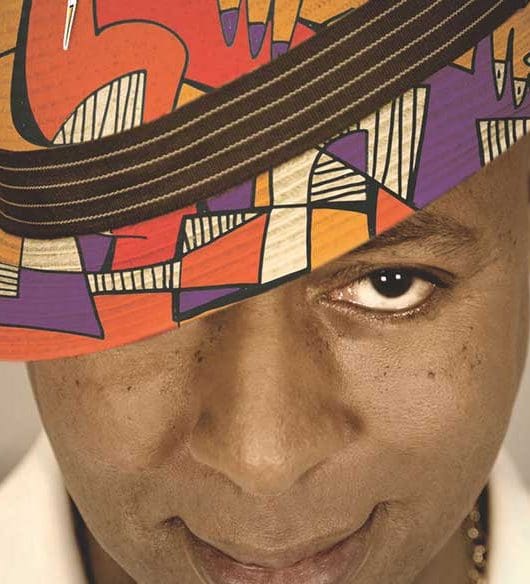

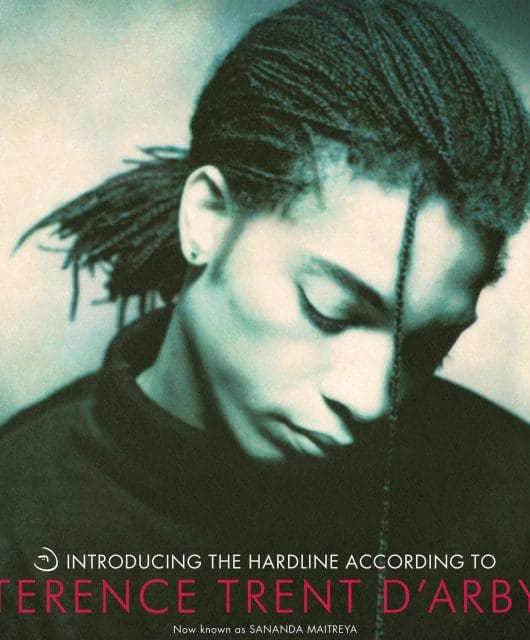

But the influence spreads far and wide, incorporating acts as diverse as Tears For Fears, Damon Albarn and Grace Jones.

Perhaps the greatest compliment bestowed upon Gary by another was the wrath of David Bowie, whose 1980 song Teenage Wildlife contains the lyrics: “Are you one of the new wave boys?/ Same old thing in brand new drag…/ As ugly as a teenage millionaire pretending it’s a whizz-kid world”.

Bowie’s antipathy only emphasises his own fear at witnessing the young, successful upstart reflected in his own image.

A key factor in Numan’s lasting appeal is that he is so sampleable – and this is particularly true of The Pleasure Principle.

The album is stuffed with otherworldly ear candy that cries out to be repurposed. A Numan sample is a like a mini pocket-rocket, guaranteed to propel a track up the charts.

Basement Jaxx, Sugababes, Armand Van Helden, Afrika Bambaataa and GZA (Wu-Tang Clan)… have all benefitted from his magical elixir.

The best way to experience these familiar riffs, though, is by tracing them back to their source.

Hearing them in situ on The Pleasure Principle, these gems aren’t buffed up to a shine; rather they are covered in grit and dirt, but remain twinkling diamonds in the rough.

Gary Numan: The Pleasure Principle – The Songs

Airlane

The atmospheric instrumental opener begins with those characteristic synths that forge Gary Numan’s signature sound. Even if you’ve never heard this song in your life, we’ll wager you’ll instantly identify the artist as Numan. The hi-hats build up the tension before ripping into the lively acoustic drums, which drive the track forwards. It’s the sound of a live rock band, almost glam in its groove, albeit with a futuristic, synthed-up arrangement.

Metal

A classic Numan earworm and early highlight, Metal is announced with a nagging synthesizer riff and percussive electro hit, before Cedric Sharpley’s drums come thundering in. One of the more instant and immediate tracks on The Pleasure Principle, Metal has a sleazy, gritty sound that’s accentuated by the primal and repetitive riff, doubled on the bass and synths – it wouldn’t feel out of place on Arctic Monkeys’ AM. That’s until an ice-cold synth slices straight through it. The song has seen various incarnations over the years, with the root of its lyrics dating back to Tubeway Army’s Replicas sessions, while Numan later reworked its top line melody into Moral on 1981’s Dance.

Nine Inch Nails later covered Metal and it’s not hard to see why.

Complex

The second single off the album is the closest you’ll get to a Numan ballad. One of the more sedate, dreamy, and understated tracks on offer, but beautifully so, it shows a softer, gentle side to Numan’s writing, though still containing that sense of paranoia in the lyrical subject matter. It begins with an atmospheric opening, before the drums roll in. The viola from Chris Payne, when combined with the droning, heavily-flanged, phasing synths, creates an interesting texture that elevates the record. It peaked just outside the Top 5 of the UK singles chart.

Films

Films is the perfect example of how effortlessly Numan invokes a mood on his records. It opens with a droning synth, then those live crunchy drums and bass guitar arrive, accompanied by classic Numan synths. The hypnotic groove is understandably a favourite among the hip-hop community. It has been sampled on a range of records including A Future Without A Past… by Long Island collective, Leaders Of The New School (featuring a young Busta Rhymes), and various members of the Wu-Tang Clan.

M.E.

The ‘M.E.’ stands for ‘Mechanical Engineering’ (the only song title technically not a single word). That meaty synth riff is instantly recognisable to a whole new generation of millennial clubbers as Basement Jaxx’s Where’s Your Head At (which incidentally also samples another Numan track from follow-up Telekon, This Wreckage). Try listening without screaming “Where’s your head at?” over the lead hook. But the original is a classic in its own right, if a little meandering in the final third. At 5:38, it’s one of the longer tracks on the record and arguably the final two minutes devoted to an extended synth outro could easily be shaved off to its improvement – but that’s splitting hairs.

Tracks

The introduction of a broken-chord riff played on piano is an unexpected but welcome addition to the instrumentation, before the crashing synth invasion, and driving 4/4 beat from Sharpley. Once the main track gets underway, it has something of Enola Gay about it (though pre-empting the OMD song by a year). As it returns once again to the piano motif for the outro, violin from Ultravox’s Billy Currie seeps in on the fadeout.

Observer

This track is so similar to Cars, you’d be forgiven for at first thinking it’s an early demo of the single. But Observer is a neat exercise in its own right. If anything, its comparative obscurity compared to its more well-known and omnipresent sibling actually plays to its advantage in retaining its freshness. The way the drum groove locks in with the synthesizers gives it a punky attack. It’s over almost as quickly as it begins, but leaves the listener wanting more.

Conversation

A slower track with lots of space and a menacing groove. On this occasion, Billy Currie’s violin riff has echoes of Bollywood, and again provides an unusual organic texture when combined with the electronic synths. At over seven-and-a-half minutes, Conversation is presumably Numan’s stab at electronic prog-rock, though four minutes would easily have sufficed.

Cars

What really is left to be said about Cars that isn’t known already? Numan’s biggest hit is a bona fide classic. What this track does so effectively is to distil everything that’s great about The Pleasure Principle into one neat, accessible – and radio-friendly – package. All the elements are there: the signature Numan synth sounds, more hooks than a Peter Pan convention and a characteristic vocal. Pure genius, and the perfect gateway for exploring Numan’s wider catalogue.

Engineers

A seamlessly endless drum roll morphs into a marching-band snare drum. When it is then joined by foreboding bass stabs, the effect is akin to a warning alarm announcing the onset of the robot apocalypse. It’s Numan at his most experimental, accentuating the dystopian vibe with futuristic ambient sounds. His vocal melody is tracked by the synth beneath it. The sense of unease is enhanced by the fact that, from start to finish, Engineers never resolves into a chorus, it simply marches into eternity.

30th Anniversary Edition: Bonus tracks

Random

A spacey instrumental that opens with a droning synth, before a disco beat eventually comes in, following the classic synth wash. Pop fact: The 1997 Numan tribute album that helped to usher in his reappraisal was named after this obscure cut, although the song itself doesn’t actually feature on the compilation.

Oceans

Another instrumental, though more chilled out without the Gardiner/Sharpley rhythm section. It’s built upon arpeggiated piano doubled with synth, interspersed with bleeps that recall either a hospital bed’s vital signs monitor or an uprising from the self-checkout tills in Asda.

Asylum

True to its name, it’s an eerie soundscape with twinkly pianos and synth strings, giving a sense of foreboding dread, like something out of an apocalyptic Hitchcock thriller from the future. Asylum demonstrates that Numan could have had an equally fruitful career writing sci-fi soundtracks.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!