Left without any band members following a Malcolm McClaren-led mutiny, Adam regrouped stronger than ever and made the seemingly unlikely transformation from leather-clad abrasive post-punks to vibrant chart darlings with Kings Of The Wild Frontier

The scent of revolution hangs heavy in the air. Enter a motley crew of reprobates (who nonetheless look so dashing), arriving on a thunderous roll of tribal drums to herald in a new fashion. A new royal family, a wild nobility, with their own soundtrack to boot: Antmusic. At their head, their shamanic leader, Adam Ant.

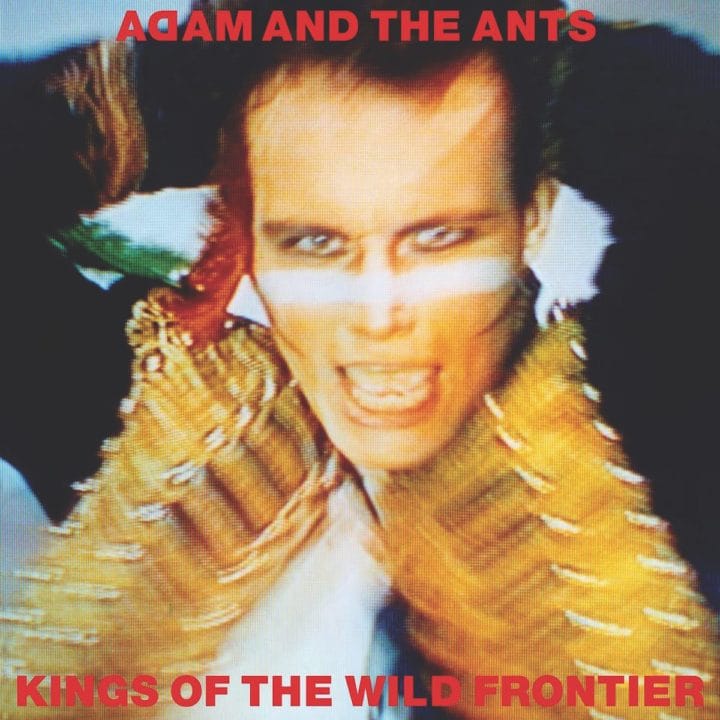

Released on 7 November 1980, the Adam Ant songs on Kings Of The Wild Frontier are a call to arms. And an extremely compelling one at that. For something so inherently bizarre, it’s shamelessly self-assured, so brimming with confidence and laden with swagger that it’s literally drunk on its own hype.

Thankfully, it’s as wonderful as it is brazen. Far from empty posturing, Kings Of The Wild Frontier fully delivers on its manifesto. This Adam Ant album topped the UK charts and won a Brit Award, while pre-empting even greater success for its swiftly-released follow-up.

Call To Arms

Culturally, it ushered in a new era – paving the way for the second British Invasion. Some retrospective appraisals pitch Kings Of The Wild Frontier as the very catalyst that shifted the paradigm from punk to New Romantic. But while the movement may have borrowed his frilly blouses and impeccable coiffure, Ant was entirely distinct from the Blitz Club scene that launched the likes of Spandau Ballet and Visage.

In reality, though often lumped in with the New Romantics – much to his chagrin – Adam emerged from that earlier mid-70s punk scene, lorded over by Malcolm McClaren. His pre-Ants pub rock group, Bazooka Joe (in which he played bass), famously gave the Sex Pistols their first opening. And his first forays fronting his new group, the Ants, were characterised by an angular art-rock.

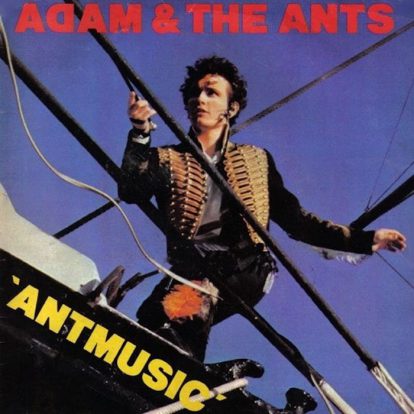

But ultimately, punk’s destructive nihilism would prove too limiting to contain Adam Ant’s vision. While much of that scene was fixated on tearing down the old order – as if that was an ultimate end in itself – Kings Of The Wild Frontier is more concerned with building something new and exciting in its place. Adam retained the attitude and ‘last gang in town’ mentality, but laced it with vivid colour, oversized characters and playful surrealism. Even down to the cover image, it’s so over the top, camp and bursting with life – a notable contrast to the austere monochrome stylings of their debut, Dirk Wears White Sox from the previous year.

Bursting With Life

What’s most remarkable about Adam And The Ants’ phenomenal rise is how unlikely it might have seemed. At the turn of 1980, the future looked uncertain, if not outright bleak – small victories tempered by just as many defeats. While their debut album had just topped the newly-introduced independent album charts, it was a consolation of sorts, having been dropped by Decca after just one underwhelming single.

Despite a rippling groundswell of support (buoyed by several sold-out shows), early reviews were scathing, and the band suffered much hostility from the music press. To cap it off, their new manager, Malcolm McClaren – who had been brought in to revive their fortunes – delivered the ultimate stab in the back by dumping Ant and poaching his bandmates to form Bow Wow Wow.

Turning Point

As it happens, McClaren’s mutiny proved to be the key turning point. Rather than ceding defeat, Ant quickly assembled a new band – re-tooled, refined and supercharged. Adam was now ready to do battle, flanked on either side by his new secret weapons: Marco Pirroni on guitar and producer Chris Hughes aka Merrick on drums.

Pirroni introduced a distinctive twangy guitar style, combining 1950s rockabilly with influences from Spaghetti Western composer Ennio Morricone. What’s more, Pirroni became Adam’s writing partner, a relationship that extended well into Ant’s solo years. One YouTube commenter (@ydderynnad) astutely summarises Pirroni’s contribution: “He found the sweet spot of not playing too much while making every note he played count.”

Meanwhile, Hughes first met their acquaintance as a producer hired to salvage earlier single, Cartrouble. Though an unproven rookie at this point, his production nous became another key ingredient in bringing the whole chaotic mess together. Hughes’ ear for pop hooks is attested by his later work with Tears For Fears, co-writing Songs From The Big Chair’s Everybody Wants To Rule The World, which Roland Orzabal had previously cast aside. It became a double score when Hughes was subsequently recruited as the band’s new drummer. Bassist Kevin Mooney and secondary drummer Terry Lee Miall completed the gang.

A New Fashion

It’s only when you attempt to define the core essence of Kings Of The Wild Frontier that you realise just how difficult a task it is. Certainly, there are hooks galore, but what exactly do you hang them on? Most pop classics can be appraised via the ‘campfire singalong test’: once all stylistic trappings have been removed, they’ll hold their own distilled down to a bare melody and a chord progression. Not so with Kings Of The Wild Frontier. In this case, the dressing is the substance.

By and large, the record eschews traditional song structures, often with no discernible verse/chorus division. Most of the tracks have a circular quality, built on revolving grooves, riffs, chants and soundbites that weave in and out – chaotic yet bound in a precariously balanced perpetual motion. It’s a peculiar juxtaposition of intangibility and weightiness.

For a chart-topping group, their sound totally bucks the commercial trends of the era. The Ants avoid the temptations of synth-pop, with neither synthesizer nor drum machine in sight. While nothing else really sounds anything like them, they form part of a niche that included Siouxsie And The Banshees, and (yes) Bow Wow Wow – blending post-punk with tribal rhythms and layers of complexity. Their two-drummer line-up was integral to the sound.

Collage Of Sounds

It’s a strange blend that really shouldn’t work on paper: Spaghetti Western meets Captain Pugwash and Dick Turpin. And the record’s positively stuffed with American pop culture references, borrowing liberally from film, music and fashion. The eclecticism draws further influence from Native American culture and African Burundi rhythms. Yet for all the global inspiration, it remains absolutely and unmistakably English to the core.

There are parallels to be drawn with the ‘sound collage’ concept taking hold in the early 80s. The idea of pulling in fragmentary references from elsewhere – both those knowingly borrowed from pop culture and those decidedly more obscure – and then blending them together to create something entirely new and original.

Whereas other pioneers experimented with literal sampling of existing recordings, the Ants simply absorbed and interpolated these influences into their own performance. Like Ant, Pirroni was the master of this, weaving motifs from classic cowboy movie scores and other references into his sparse but vital contributions. It’s an endlessly rewarding game in itself, spotting the various easter eggs hidden within.

Wry Humour

Periodically throughout, Ant helpfully reminds the listener of who and what they are listening to, should they have momentarily forgotten… (Antmusic, Ants Invasion, etc.). It’s the kind of comically overblown self-aggrandising often reserved for hip-hop, but the braggadocio is laced with wry humour and knowing winks.

Adam has always been wonderfully in touch with the absurd (consider the demo from around this period, Omelette From Outerspace). To a large degree, he sits within that great lineage of English surrealists including Monty Python, Syd Barrett and Robyn Hitchcock.

That tussle between pop and art remains an essential element of the band’s ongoing appeal. In many ways they are the ultimate fringe act, a sideshow curiosity, Yet, equally Adam is in every way the consummate pop star, destined to rule atop the charts, and purpose-made for the promo video.

An 80s Slipknot?

The album’s sleeve art is in itself a piece of pop history, and an enduring image of the 80s. Shot by renowned photographer (and one-time member of The The) Peter Ashworth, it’s a photograph of a video recording of the Ants screen test ahead of an appearance on Top Of The Pops. Essentially, a picture of a picture, its intentionally pixelated form is one step removed from reality, much like Adam Ant, himself. It’s an effect that Ant would reprise – see Stand And Deliver and the 1983 reissue of Dirk Wears White Sox.

When success arrived, it came very quickly – perhaps too quickly to keep a real handle on. In just a matter of months, Ant went from obscure punk to Michael Jackson’s fashion advisor. The pace they set was impossible to sustain. Compared to the fanfare in Britain, Adam didn’t quite conquer America in the way he deserved to. But arguably those that followed in his wake, from Duran to Spandau, owe at least some of their Stateside success to the considerable splash that Ant created.

Yet the ongoing global influence of Kings Of The Wild Frontier, and its central character created by Adam Ant, spreads far and wide to this day. Demonstrating the breadth of influence, there are echoes in phenomena as varied

as Disney’s Captain Jack Sparrow through to the rubber-masked nu-metal band, Slipknot (that may sound a stretch, but check out their uniform dress code, gang mentality, parent-baiting and primal dual drumming).

As Exciting As Ever

Slightly closer to home, the Ants’ cartoonish interpolation of cowboy and Western themes is a precursor to Mick Jones’ Big Audio Dynamite, a sound revived in the noughties by Gorillaz with their various references to Clint Eastwood and Dirty Harry. The Dandy Highwayman character (explored on follow-up, Prince Charming) is even referenced in a children’s picture book from 2011, The Highway Rat, by the authors of The Gruffalo.

Surely nobody – aside from Adam Ant himself, perhaps – could have predicted the incredible U-turn that saw them shift from fetish-obsessed, leather-clad punks to Smash Hits darlings. To quote Ant himself in Don’t Be Square (Be There): “You may not like it now but you will.”

Even more amazingly, the Ants achieved the overhaul without losing any of their potency. They remained as bizarre, chaotic, cerebral and exciting as ever. No method in their madness. Perhaps, but who needs Beatlemania, when we’ve got the Ants Revolution.

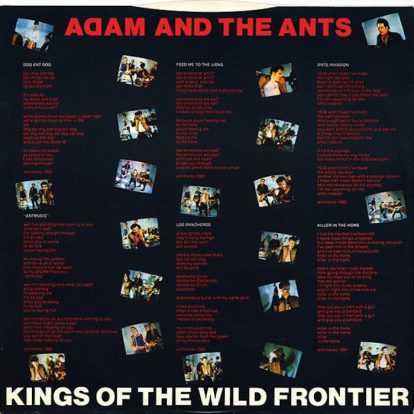

The Songs

Dog Eat Dog

Ant was the master of the attention-grabbing intro – those thundering drums (apparently designed to prevent a radio DJ talking over them) have become his calling card. Call-and-response yelping and cheering are set to Marco’s 50s-style tremolo guitar, straight out of a country tune. It’s a wonderfully chaotic post-punk concoction – almost proto-rap with its indiscernible structure, built on riffs and chants over a hypnotic groove. Their first true chart success, it rocketed into the UK Top 5, landing at No.4.

AntMusic

Another earworm intro – and today instantly identifiable – with the percussive clicking of drum sticks, before those characteristic toms come in. This is the call to arms. Their manifesto – “That music’s lost its taste, so try another flavour: Antmusic” – is a reference to the all-pervasive disco of the late 70s. The obligatory punk staccato “Oi!” punctuating every note of the bar is contrasted with more 50s guitar from Pirroni. The third single to be released off the album gave them their highest UK chart position to date, a UK No.2 (kept off the top spot by John Lennon’s posthumous release of Imagine, following his recent death). In Australia, however, it did one better, topping the charts for over a month. Demonstrating its ongoing appeal, the song makes an appearance in the ubiquitous Marvel universe courtesy of Ant-Man (well, obviously).

Feed Me To The Lions

At its core, Feed Me To The Lions is a more standard spit’n’sawdust rock’n’roll track, and the most melodic and singalong offering so far. There’s a real rockabilly flavour, with a frenetic bassline and an almost barbershop-esque, doo-wop-style chorus (or at least Adam Ant’s skewed interpretation), with a rather camp “Hey ho!” sailor-like chant underneath. It’s a cracking tune, and even rather pretty, despite the lyrical subject matter, that most New Wavers would be happy to have in their arsenal. It feels a little bit throwaway, though, when compared to the revolutionary onslaught that precedes it.

Los Rancheros

A clear showcase for Pirroni, he delivers a very twangy, Spanish tremolo guitar sound with a memorable melodic riff. It kicks off like a classic 60s guitar instrumental, like something performed by The Shadows or Dick Dale, until Adam’s vocals kick in and takes it somewhere else. A clear example of the melding of transatlantic influences – the very obvious cowboy stylings, complete with pistol sound effects, with the very British vocal delivery. The end result is something akin to a novelty song, or radio jingle, from the 50s or 60s.

Ants Invasion

No thunderous drums this time, instead an eerie double-tracked guitar line panned hard left and right, playing a riff out of a horror movie or sci-fi soundtrack. The Ants now venture into dystopian post-punk territory – compared to the opening tracks, the space proffers a menacing quality, as the tension builds. A storytelling narrative song, as the hero of the track ponders whether he has made the right decision (about what exactly?), becoming increasingly more frantic and exasperated as the track goes on. The stripped-back middle eight is sweet, almost inviting Ray Davies comparisons, with Adam’s over-egged London twang heard over chorus-laden guitar… before this is ripped apart by heavy metal guitars. Ants Invasion demonstrates a greater depth and breadth to their oeuvre.

Killer In The Home

The trademark thunderous drums again, but slower now, propelled along by the repetitive and revolving bass guitar part, with spacious strummed tremolo chords ringing out on the guitar. It’s a slow builder, gradually rising in tension. Halfway through, a marching band snare comes in, followed by nice chorus guitar work. Just as the song appears to be petering out, it comes back stronger in the final quarter with more tribal drums and wailing from Ant as he cries: “killer in the home!” A final twist is delivered from Adam in a subversion of the line as he says “the killer is the home”. Another post-punk gem.

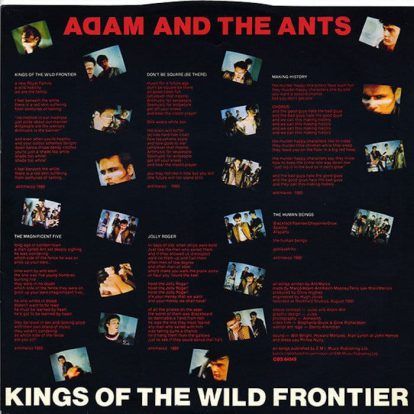

Kings Of The Wild Frontier

Another call to arms, like Antmusic that opens the record, this is a bold declaration of the band’s manifesto. Kevin Mooney’s bassline is a fundamental element of the track. Lyrically, it’s one of several songs leaning on Ant’s interest in Native American culture: “Beneath the white there is a redskin suffering.” Whether used ironically or not, it’s not an accepted term today, of course – although Ant’s sentiment is certainly one of solidarity. On first release as a single, its sheer chaotic majesty was too ahead of its time for the charts, whimpering beneath the Top 40, stalling at No.48 in the summer of 1980. Yet the Ant revolution was in full swing by the time of its re-release just over six months later, when it reached a more respectable No.2.

The Magnificent Five

The music fades up in to a very repetitive and extremely busy number, with more 50s rockabilly from Marco and some huge power chords thrown in for good measure. Lots more “Hey! Hey! Hey!” chants punctuate the track. The name, of course, is another one of many Western references. One of the more straight-up punk tracks – sharing some DNA with The Clash.

Don’t Be Square (Be There)

This starts off sounding very different – almost pure disco, with very slinky, trebly guitars and a four-to-the-floor beat, before getting a post-punk makeover. With its art-punk meets dancefloor crossover, it’s the closest you’ll get to Talking Heads this side of the pond. As well as reminding everyone of the new sound in town (Ant Music, of course), Adam repeats the line “Dirk wears white sox” (the title of their debut album, for which this song was originally intended). Elsewhere, the lyrics seem to be anticipating the Antmania that would soon follow. To quote Adam, it’s just “Good clean fun – whatever that means.”

Jolly Roger

Does exactly what it says on the tin: a camped-up, over-the-top pirate sea shanty, that would give Blackbeard a run for his money, complete with references to the gallows and a twee, whistled riff. True to the subject matter, it’s stuffed with more hooks than a Peter Pan convention. It’s a total novelty track, for sure, but this song in some ways could well be one of their most important – clearly being the genesis of later career highwater mark, Stand And Deliver with the immortal line: “It’s your money that we want and your money that we’ll have!”

Making History

The penultimate track starts with a chaotic guitar maelstrom, with those classic chugga-chugga Burundi drums, before a melodic vocal refrain comes in from Adam, and more rockabilly stylings courtesy of Marco. Making History is a textbook example of their ability to create something so utterly chaotic yet instantly catchy and hook-laden. Echoes of The Clash, again, though with almost a ska flavour in the bassline, if not for the tribal drumming.

The Human Beings

Some today might class Adam’s fixation with Native Americans as cultural appropriation, but arguably he was extremely progressive in his support of indigenous cultures when it wasn’t in fashion, highlighting their plight at the hands of the white man. He cites various tribes (Blackfoot, Pawnee, Cheyenne, Crow, Apache, Arapaho), and apparently declared during one live performance: “They are human beings, and we are the savages.” The title itself is another cinema reference, nodding to the 1970 film, Little Big Man, starring Dustin Hoffman. Compared to the big bold entrance, it’s a somewhat understated end to the record, the arrangement becoming sparser and gradually fading out to nothingness.

The Videos

Kings Of The Wild Frontier

Treatment wise, it’s surprisingly simple for a group known for their theatrics – just the band performing, squashed into the corner of a white-walled room. But the austere set dressing acts a blank canvas for the vibrant, costumed gang to do their thing, enhanced by vaguely psychedelic shadows projected onto the wall. It’s the performance that makes it compelling, tension heightened by jarring jump cuts. The video was directed by Stephanie Gluck and Clive Richardson, the latter of whom helmed promos for Tears For Fears, the Banshees and Depeche Mode.

Dog Eat Dog

You don’t need to know anything about Adam Ant to grasp that he was tailor-made for the pop video format. Ant would often storyboard and co-direct his promos and has since noted how visualisation concepts would often form during the initial genesis of writing or recording the song. The Ants were a very visual band, fashion and aesthetics have always been a key ingredient of their make-up. Like Antmusic, this was directed by Steve Barron. Ant the compelling showman fronting the band, with his arms flailing all over the place, in total command.

AntMusic

Set in a nightclub, the video builds on literal visualisations of the lyrics: out with the old (disco) and in with the new sound, as they unplug the jukebox with a comedic, oversized plug. The band feel so fully-formed and complete, a force of nature. The video features Adam’s then-girlfriend, Amanda Donohoe (who would again appear in the Stand And Deliver promo). This was one of the earlier promos helmed by the visionary Steve Barron: pop video director extraordinaire, whose work included Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean, Dire Straits’ Money For Nothing, and a-ha’s Take On Me. His direction here, actually predates his later hits with those artists, again highlighting Ant’s pioneering steps in the visual aspects of pop.

For more on Adam Ant click here

“I’m proud of the fact that we actually got a record like Kings Of The Wild Frontier”

The Adam Ant Classic Pop interview

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.