It’s Immaterial interview: Getting their house in order

By Wyndham Wallace | September 5, 2022

In 2020 It’s Immaterial released their first new album since 1992. That year, members John Campbell and Jarvis Whitehead opened up to us about their three-decade struggle to complete it…

It’s late June, and, across the city, fans are still revelling in the news that Liverpool FC have finally been crowned Premier League champions. It’s been 30 years since they last triumphed in the top tier and, despite an ongoing coronavirus lockdown, fireworks continue to light up the skies most nights.

There’s another quieter celebration going on this afternoon, though: almost 30 years after they began work on it, It’s Immaterial’s John Campbell and Jarvis Whitehead have just received the test pressings for their third album.

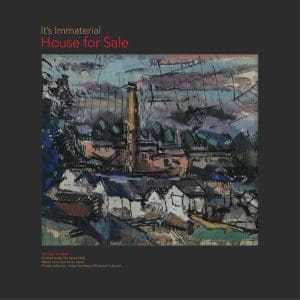

House For Sale belatedly follows the release of 1990’s masterful but neglected Song, recorded with Calum Malcolm around the same time as he worked on The Blue Nile’s Hats, with which it shares many magical qualities.

It’s even longer – 34 years! – since It’s Immaterial first won hearts and minds with their single hit, the eccentric but, to all who heard it, unforgettable Driving Away From Home (Jim’s Tune), which ran out of gas just inside the Top 20.

So, might House For Sale be their Jürgen Klopp, sending them, like their adopted hometown’s famous Reds, to the top?

“Oh!” singer and lyricist Campbell gasps, as amused as he’s astonished. “It’s not our position to say that, is it? But we’re back on the field, playing football…”

The journey towards House For Sale’s overdue but welcome release has been a long, frustrating one, both for the duo and their small but devoted army of fans.

Begun excitedly with Malcolm soon after Song won widespread plaudits then swiftly evaporated with the dissolution of their record label, the album has suffered multiple delays, and in the intervening period only three Itsy – as their fans call them – songs have been released, the last in 2002.

In fact, aside from Campbell’s cameo on Gone From Here, China Crisis vocalist (and Campbell’s near-neighbour) Gary Daly’s 2019 Classic Pop Album of the Year, both he and Whitehead have been otherwise entirely absent from the pop landscape for three decades.

Campbell’s spent recent years working with his partner Moira Kenny as The Sound Agents, oral history specialists who, their website explains, “give seldom heard voices opportunities to share their stories through engagement with the arts”, while Whitehead has worked as a music teacher.

But frustration is nothing new to It’s Immaterial, and, after its original tapes spent decades gathering dust on a shelf, House For Sale is at last ready. Its majesty is a remarkable testimony to their perseverance.

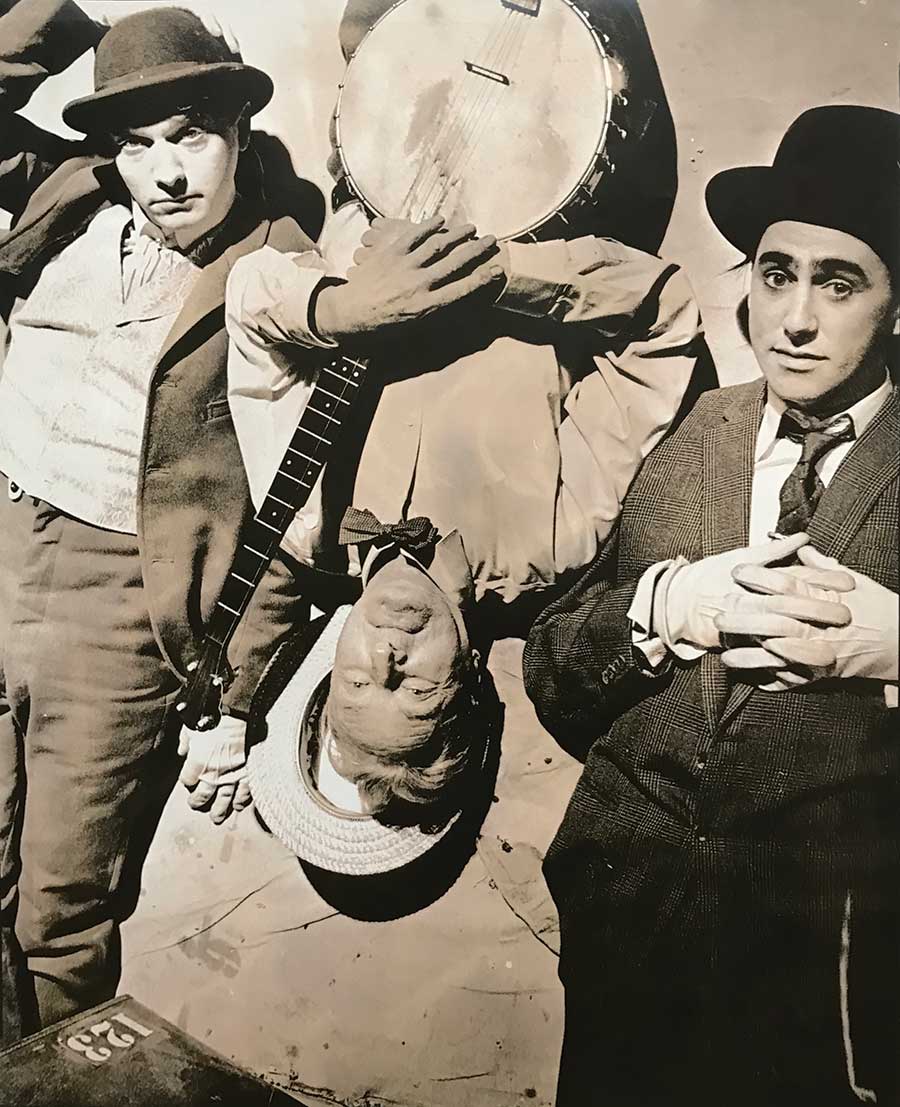

In their initial incarnation as turn-of-the-80s art school pranksters, things were easier for It’s Immaterial, who were already well connected.

Founders Campbell, Martin Dempsey and Henry Priestman had all played in the disconcertingly named Albert Dock And The Cod Warriors, who’d taken over Deaf School’s rehearsal studios at Liverpool Art College in the mid-70s after they’d signed to Warners, and later they gave Bill Drummond’s and Holly Johnson’s Big In Japan their first show as opening act.

It was Pete Fulwell, meanwhile – managing director of the city’s famed Eric’s Club, where Whitehead first saw Campbell in 1976 supporting the Sex Pistols with Albert Dock – who encouraged them to take things more seriously, offering them a Thursday night residency which provoked their transformation into Yachts, who soon signed to Stiff Records.

Campbell, however, left after just one single, 1979’s Suffice To Say. The next year, the newly-formed It’s Immaterial released their debut 7″, Young Man (Seeks Interesting Job). That it was a cover of a swinging 60s tune by The First Impression was little surprise.

“We used to get together and play all kinds of American surfy punk things from the 60s,” Campbell recalls. “Eventually they started this thing in Liverpool called Larks In The Park, and we played a set of these songs there. That was where the Itsy material started.”

Fulwell soon stepped in again, not only paying for and releasing their material – 1981’s A Gigantic Raft In The Philippines provoked the first of four Peel Sessions – but also, not long afterwards, offering to manage them. Despite this momentum, “we always seemed to be thrown in with deals,” Campbell recalls.

“People would be doing one with somebody like Wah! Heat and then say, ‘Why don’t you have It’s Immaterial as well?’ We were quite often an afterthought.”

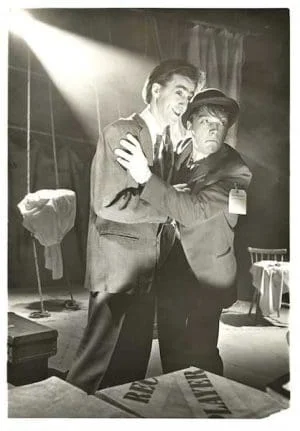

Nonetheless, following a personnel reshuffle – with Priestman leaving to form The Christians, and the band reduced, by 1983’s White Man’s Hut single, to just Campbell and Whitehead – it was lack of thought altogether which held back It’s Immaterial’s breakthrough with 1986’s Driving Away From Home, their second single for Virgin Records-backed Siren, where they’d settled after a brush with Warners.

“We had no intimation the song was going to be as successful as it was,” Whitehead laughs, “and the record company didn’t either!”

As radio and a Top Of The Pops appearance propelled them up the charts, the label ran out of stock. “It got to No.18,” Campbell sighs, “and stopped like a stone.”

Such disappointments set a pattern for what followed. A reissued single, Ed’s Funky Diner, barely scraped the Top 70, and their debut album, Life’s Hard And Then You Die – whose completion had been delayed while the label sought to exploit Driving…’s success – only reached No.62.

A subsequent European support tour was also cancelled following inopportune interview comments about their hosts, Les Rita Mitsouko.

Even when they made it back to the studio to piece together Song – which, with its emphasis on spoken word ‘sudden fiction’, was intended as a more subdued, filmic nod to the likes of Raymond Carver, Shelagh Delaney and American broadcaster Studs Terkel – the extended sessions in Calum Malcolm’s East Lothian studio, Castlesound, proved so intensive Whitehead suffered a breakdown.

Furthermore, if Song’s birth wasn’t easy, its release was even tougher: Siren closed soon afterwards.

Unbowed, Campbell and Whitehead accepted an invitation from Malcolm to return to Castlesound in August 1993, enthused by both their own and the media’s response to Song.

“He was hoping to review a new piece of recording equipment that was out at the time,” Campbell remembers, “a sort of eight-track cassette recording device. He seemed to really enjoy working with us.”

This time, the process was far less extreme for Whitehead. “These tracks were more liberating,” he says, “because we didn’t have any of the cerebral constraints we seemed to have with Song. But after that we came back down for family reasons and all kinds of…” He pauses. “We had to cut the recording sessions short. Then we forgot about the tapes for a while.”

Whitehead’s discreet reference to “family reasons” is tactful: a few days later, Campbell elaborates in more detail via email, explaining that, some months before, his then partner had been diagnosed with cancer.

“We decided to carry on as normally as possible,” he writes, but life didn’t turn out normal, and it was while he was in Scotland that he learned she’d have to undergo surgery.

The following June, aged 32, she passed away. Afterwards, House For Sale remained off the agenda. Instead, Campbell confides, “I was trying to support other family members and re-establish personal drive and direction.”

He and Whitehead continued to meet regularly, but it wasn’t until 2013, when Whitehead was moving home, that he stumbled on a box containing the recordings they’d made for House For Sale. The discovery represented the start of what became a seven-year endurance test to finish the album.

First off, the technology Malcolm had used was now obsolete, so to hear the music the pair had to find someone to transfer the tapes.

Liverpool’s Elevator Studios managed the task, but they then discovered that some of the material had suffered digital decay.

“It took us quite a while just fixing the tapes,” Campbell explains, “but we heard enough. We had up to 32 tracks of different ideas, and we had to select what we wanted to move forward with.”

“We were also mindful of how much we wanted to preserve,” Whitehead adds.

“Should it be an archive, because they were just demos at the time, or did we give way to temptation and meddle like we normally do? Some we did a lot of work to, we felt, but mostly we tried to stay loyal to the original material.”

Campbell points to the delicious Just North Of Here as remaining almost entirely as it was, while the bittersweet Summer Rain, he says, has been transformed both musically and lyrically. “There’s been a lot of time and perspiration put into things,” he emphasises. “I’m happy that they work.”

Finally, in late 2016, It’s Immaterial announced a Pledgemusic campaign, but there were further hurdles to clear. For starters, Campbell received his own cancer diagnosis around the same time, forcing him to conduct the campaign from his hospital bed.

As if that weren’t enough, although they rejoiced in achieving their financial goal and, following extensive treatment, Campbell’s cancer went into remission, Pledgemusic collapsed, taking half their funding with it.

“We managed to pay the recording studio and the engineer that we used,” Campbell says, “but I think we lost something like £9,000. It’s a peculiar position, because obviously we want to honour those pledges that people have made. It’s taken a long time to dig ourselves out of it.”

To do so, they turned to another fundraising platform, JustGiving, but even after another successful crusade, fate hadn’t finished its meddling.

As the album went into production, coronavirus arrived, shutting down the record’s manufacturers for almost three months.

In fact, it’s literally as they begin discussing the album’s seemingly never-ending gestation with Classic Pop that a courier delivers their white label pressings.

That neither of them has a record player with which to listen to them seems, after all they’ve been through, like a minuscule problem.

For It’s Immaterial fans, Campbell and Whitehead’s monumental efforts have been worthwhile. To others, in addition, their resilience should be inspiring.

Furthermore, this time, one hopes, luck will be on their side.

As good as anything they’ve ever recorded, House For Sale represents another glorious dip into Blue Nile territory, but it’s made distinctive as much by Campbell’s intimate lyrics, delicate croon and poignant spoken delivery as Whitehead’s inspired arrangements and refined performances.

House For Sale has finally come home, in other words, and home is where their great big hearts have always been. Like true champions, furthermore, 30 years of hurt have never stopped them dreaming.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!