Into the valleys: the sounds of Wales

By Classic Pop | February 22, 2023

The music of Wales can draw on a rich and rootsy heritage when it needs to reinvent itself… By Jonathan Wright

The figure dressed in black has tangled hair and looks directly at the camera. For all it looks like a mizzly day, he wears dark glasses. Behind him lies a juxtaposition of old and new.

Beyond a car with lines to suggest it could have been built in the 50s or earlier, a suspension bridge soars. It’s May 1966, the scarecrow-skinny figure is Bob Dylan and the photo, taken on the tour when Dylan’s electrified performances with the nascent Band outraged folk purists, speaks of a world still emerging from post-war austerity yet encountering, in Harold Wilson’s words, the “white heat” of technological change.

More prosaically, considering it’s the Severn Bridge we can see, then still under construction, it’s a reminder of just what a pain in the arse it could be to travel to and from South Wales.

In an image later used to promote Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home documentary, Dylan is shown waiting at the Aust ferry terminal on the muddy banks of the Severn estuary for a slow boat to the Principality.

Even after the bridge opened, the local motorway infrastructure remained shonky for years, with the Welsh section of the M4 completed as late as 1993.

“We need to remember that in the days when we [first] went to London there were no services at all,” recalls Michael Barratt, better known as Shakin’ Stevens, the most successful British singles artist of the 1980s.

“There were plenty of transport cafes, trucker places, but there was no motorway as such, and so we had to go from Cardiff to Chepstow and up to London. It would take three, three-and-a-half to four hours to get there.”

Into the valleys

Perhaps because of this comparative geographic isolation, Wales can seem like a place set apart in terms of its pop history. Think of Manchester, for instance, and there’s the galvanising presence of the late Tony Wilson, the media-savvy cheerleader for the city, and his own Factory Records and the Hacienda nightclub.

In contrast, the story of Welsh music is often told through a list of apparently disparate names: Shirley Bassey, Tom Jones, Amen Corner, Mary Hopkin, Shakey, Badfinger, Budgie and more.

If there’s a unifying narrative in this version of the Principality’s rich musical history, and it’s by no means the only version as we’ll see, it’s more around style than a particular figure or club. South Wales in particular is a place where rock’n’roll laid down deep roots.

Tom Jones, Shakey and Cardiff-born Dave Edmunds, who enjoyed a No.4 UK hit in 1979 with the Elvis Costello-penned Girls Talk and performed with Nick Lowe in Rockpile, were all born in the 1940s, and grew up steeped in the music of Elvis, Little Richard and Chuck Berry.

“I don’t think any A&R people, scouts, came down to Cardiff,” remembers Shakey of starting out. “I certainly wasn’t aware of it, but it was great for music. There were lots and lots of bands.”

Paying that forward, rock and heavy metal thrived in the Welsh Valleys in the 70s and 80s. This was music for Saturday nights in the pub and it clearly had an effect on local musicians.

When husky-voiced Bonnie Tyler, hitherto known for country-tinged pop hits such as It’s A Heartache (1977), began working with Jim Steinman of Meat Loaf fame in the 80s, the transition in style to outright bombast seemed the most natural thing in the world, and produced the perennial karaoke favourites Total Eclipse Of The Heart and Holding Out For A Hero.

From a different angle, The Alarm, fronted by Mike Peters, grew from punk and new wave, but brought a rock anthem sensibility to such hits as Sixty Eight Guns (1983), which brought success in the US as well as Europe.

The generation terrorists

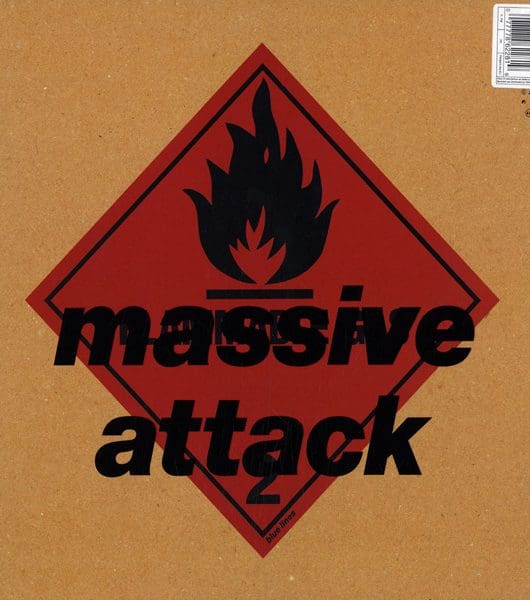

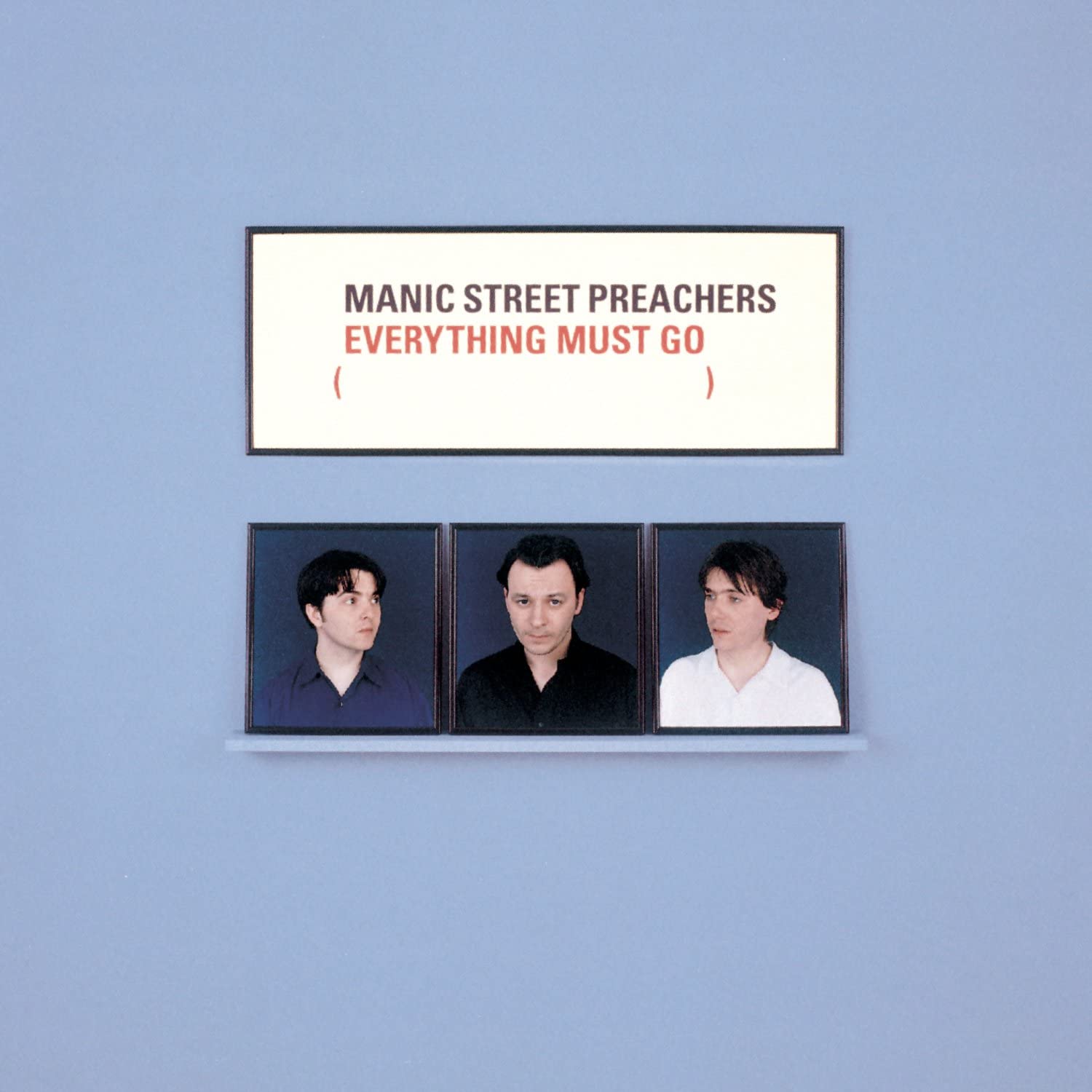

As the 90s began, one Welsh band above all proved it was possible to craft something genuinely new from rock influences. From Blackwood, Caerphilly, the Manic Street Preachers soaked up the music of AC/DC, Rush and Hanoi Rocks.

Yet, like Kurt Cobain on the other side of the Atlantic, the band’s hard rock influences went alongside a love of punk’s revolutionary spirit – it’s no coincidence MSP first came together in 1986, the same year Channel 4 broadcast a Ten Years Of Punk season.

The voracious reading of lyricists Richey Edwards and Nicky Wire, combined with singer-guitarist James Dean Bradfield’s musicianship, to create a potent brew fuelled by repeated listening to both Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite For Destruction and Public Enemy’s It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back.

It’s difficult to remember now, but early on the Manics were derided as faintly ridiculous, silly poseurs. Richey Edwards begged to differ, carving “4REAL” into his arm with a razor blade while a horrified Steve Lamacq, then working for the NME, looked on, uncertain what to do.

During this era, the band claimed they would make one great album and then split up. As Wire noted: “The most important thing we can do is get massive and throw it all away.”

In the event, the Manics did something far braver: they carried on, perennial semi-outsiders. Along the way, the trio of Wire, Bradfield and drummer Sean Moore weathered the still unexplained 1995 disappearance of Richey Edwards, with dignity and grace.

Making songs to remember

A less often highlighted element in the Manics’ mix of influences was the C86 generation of indie bands. In 1986 and 1987, Wire and Bradfield would busk in Cardiff. “The idea was to make enough money to buy a seven-inch single [from venerable record store Spillers Music] and a burger,” he told Alexis Petridis of The Guardian in 2006.

“The burgers came from Wimpy. The seven-inch singles came from indie bands no one really remembers now: The June Brides, McCarthy, Tallulah Gosh, Big Flame.” These were “fragile” and “feminine” bands that, as with the Manics, liked manifestos and were interested in things “slightly under the radar”.

As such, these were also bands heavily influenced by two Welsh groups to emerge in the post-punk era. Cardiff-born Green Gartside-fronted Scritti Politti.

Formed in Leeds in the late-70s and with a name chosen in homage of the Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci, the Scritti’s rough and ready debut Skank Bloc Bologna EP (1978) was one of the key DIY releases of the era, with a sleeve that broke down the costs of making the record.

Later, Green honed his songwriting skills to become a bona-fide pop star in the 1980s, the surface brightness of singles such as “The Sweetest Girl” (1981, and covered by Madness in 1986) sneaking personal-political messages into the mainstream.

Young Marble Giants were less commercially successful, and released just one album, Colossal Youth for Rough Trade in 1980. To quote Simon Reynolds (Rip It Up And Start Again: Postpunk 1978–1984), writing the reissue liner notes: “The Cardiff trio’s one-and-only album contains not a wasted note, barely a blemish.”

He’s right. The trio of Alison Statton, Philip Moxham and Stuart Moxham made delicate music that, if you’re looking for a contemporary reference, brings to mind a lo-fi The xx.

Yet as Reynolds also argues, for all its understated qualities, there was a “subliminal rock’n’roll element in YMG music”, albeit “rock’n’roll Anglicised, the urge to cut loose checked by a native reserve and inhibition”.

As Stuart Moxham has conceded: “In a lot of ways, I was a frustrated rocker. A lot of those riffs would sound great on loud, distorted guitars in a conventional band.”

His words are a reminder that musical histories aren’t always as straightforward as they first appear. In this context, one of the problems with seeing Welsh pop and rock as a parade of famous names is that it ignores a rich vein of songs sung in Welsh.

“There has been a Welsh-language pop scene since the 60s,” says Dr Sarah Hill, senior lecturer at the School of Music, Cardiff University. “It just never got any notice outside of Wales until the late-80s, when John Peel started playing bands like [experimental rock band] Datblygu and [punk band] Yr Anhrefn.”

When word got around

Labels such as Ankst, formed in 1988 at the University of Wales in Aberystwyth by Alun Llwyd, Gruffudd Jones and Emyr Glyn Williams, documented bands that fell in a lineage also represented by singers such as Dafydd Iwan, Meic Stevens and Geraint Jarman, figures whose careers were, in the words of Hill, “completely tied up with language activism and language politics”.

But while the Welsh-language singers of previous generations never really succeeded, bands such as Catatonia (whose guitarist/songwriter Mark Roberts played in Welsh language indie band Y Cyrff), Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci and Super Furry Animals came through as Britpop was in its pomp.

“That’s what makes 90s Welsh pop so interesting,” says Hill, “the music was good, it fit into the broader mainstream culture, and it also showed that it was possible for a Welsh band to succeed.

“It just raised a whole bunch of questions in some quarters about the fate of the language, and the concern that Welsh bands would abandon the language for a chance at mainstream success.

“That’s why Super Furry Animals’ Mwng (2000) was such a landmark album: it was in Welsh, but it was well-received by the British music press regardless. That never would have happened 10 or 15 years earlier.”

Super Furry Animals, fronted by Gruff Rhys, enjoyed a string of hits with tracks such as Something 4 The Weekend and Northern Lites; while Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci, having started out on Ankst, signed to Fontana had eight Top 75 singles without cracking the Top 40.

Enter the Welsh dragon

If the Furries and Gorky’s specialised in the kind of pastoral-tinged psychedelic pop currently being performed with aplomb by Cate Le Bon, Catatonia proved to be a more mainstream proposition.

In 1998, the band released International Velvet. It reached No.1 and spawned two Top 10 hits in Mulder And Scully and Road Rage. Much of this was down to singer Cerys Matthews.

Charismatic, gobby and, at the height of Catatonia’s success, boozy Cerys fascinated the tabloids, but in truth seemed relieved to walk away from pop stardom when the band split in 2001.

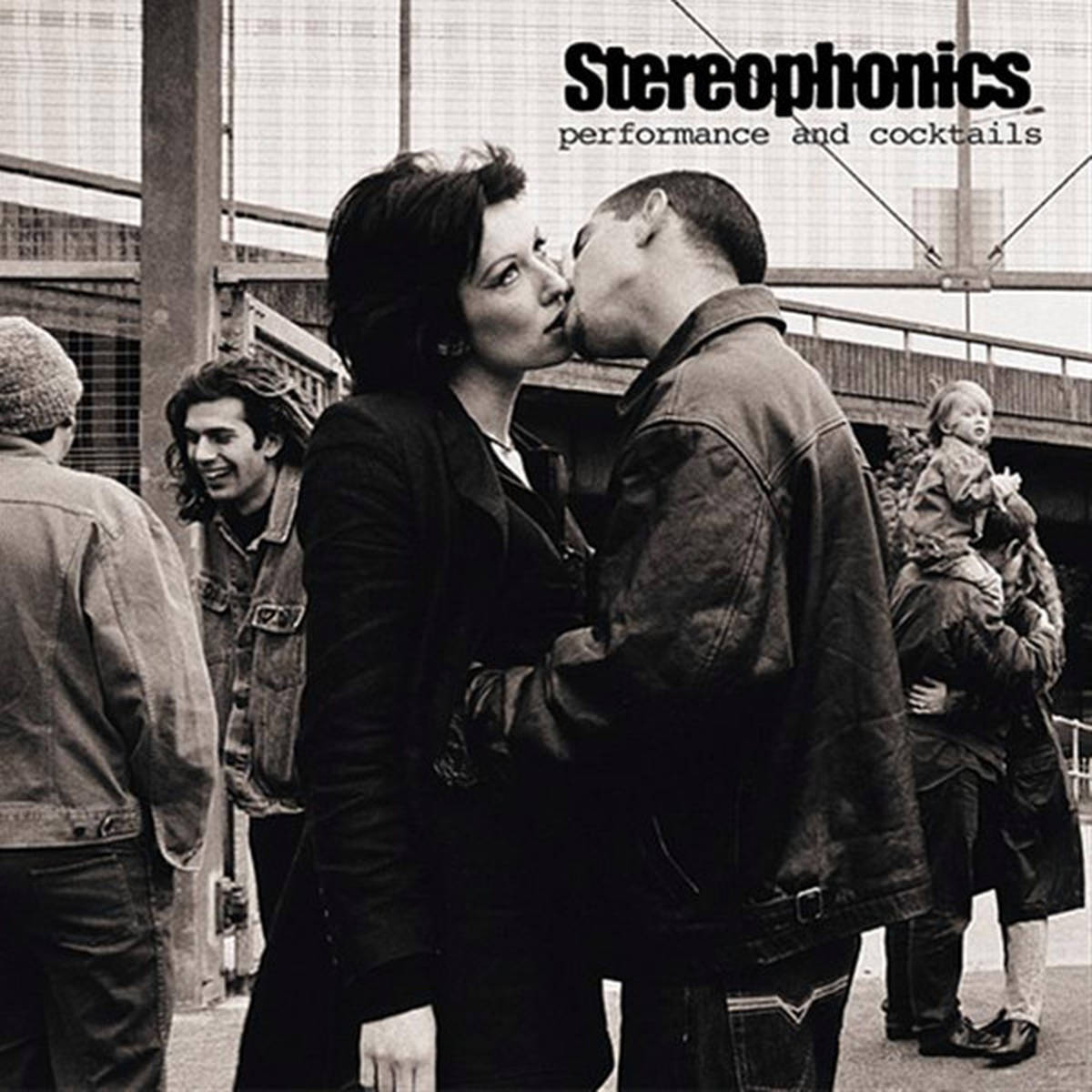

Stereophonics also enjoyed their first UK Top 10 single in 1998, with The Bartender And The Thief, from second album Performance And Cocktails.

Formed in the former coalmining village of Cwmaman in 1992 and fronted by songwriter Kelly Jones, the band have rarely been out of the charts since and recent album Keep The Village Alive (2015) was another UK No.1.

It’s tempting to see the fame of both bands – and the success enjoyed by Feeder and 60 Ft. Dolls – as a case of Welsh guitar rock being some kind of default setting.

But this misses Matthews’ eclectic knowledge of music. Or the way Jones’ best songs, from the days of Local Boy In The Photograph and the tragic tale of a lad who commits suicide, have so often been pop-tinged, kitchen-sink vignettes of working class life.

During the 00s the pop charts was suddenly bothered by an unlikely source in Welsh wonder woman Charlotte Church.

As an 11-year-old, classical music prodigy, Church was dubbed the “Voice of an Angel”, but growing up in the public eye wasn’t easy. Continually criticised and hounded by the press, the singer hit back in 2005 with Crazy Chick and found herself at No.2 in the charts.

In 2008, working among others with former Suede guitarist Bernard Butler, Gwynedd-born Duffy became an overnight sensation with Rockferry. Here was an album of blue-eyed soul that told of heartbreak and angst, but with a very British spin, as evidenced by the hit single Warwick Avenue, named for the Tube station.

Indirectly, we’re back to the place of roots music, the way that rock’n’roll, folk, blues and soul so often seem to reassert themselves within Welsh music.

When this works at its best, it’s hugely creative. In 1988, one Tom Jones reinvigorated his career by covering a floor-filling funk-soul belter in ebullient style. No surprise there, except the song was Prince’s Kiss and he recorded

it with Art Of Noise.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!