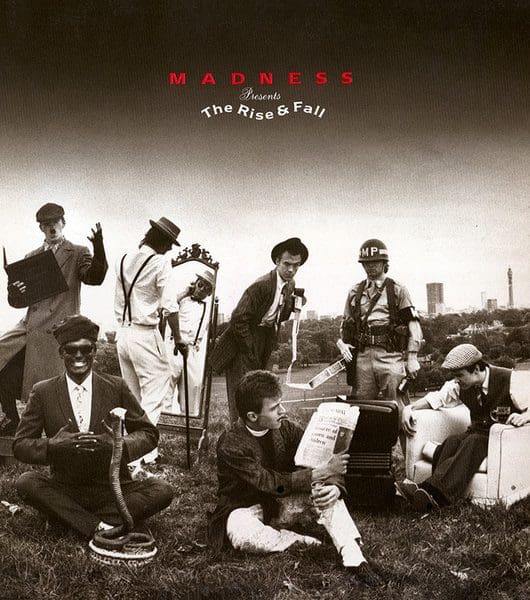

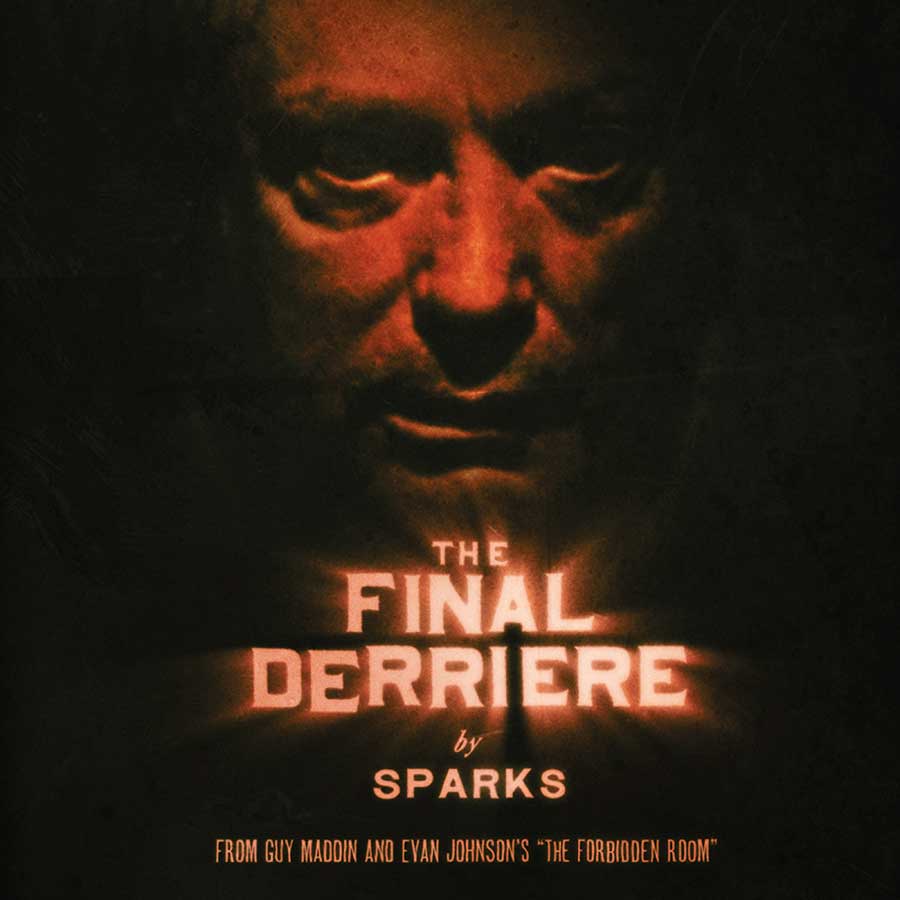

Sparks interview: “We just like doing pop music”

By Classic Pop | January 16, 2023

In 2017, Sparks returned with yet another album of brilliantly bonkers pop – Hippopotamus. That year, we talked to them about David Bowie’s artful demise, walking in parks with Brian Wilson, sex positions and… hippos! By Paul Lester

In 2017, Sparks returned with yet another album of brilliantly bonkers pop – Hippopotamus. That year, we talked to them about David Bowie’s artful demise, walking in parks with Brian Wilson, sex positions and… hippos! By Paul Lester

Sparks are an anomaly. Always have been, always will be… While they might have origins in the late-60s, the LA outliers, who began life as Halfnelson, remain a relevant and curious prospect in 2017.

Their latest collection of absurdest yet accessible modern pop, Hippopotamus, has left critics reeling… again!

The duo started releasing albums in the early-70s, their third, Kimono My House (1974), a distant relation of Roxy Music’s Country Life, David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs and 10cc’s Sheet Music, but no way are they nostalgists peddling their wares on the retro-glam circuit.

They pared down to a duo and made a purely electronic album in 1979, No.1 In Heaven, with Giorgio Moroder that anticipated the synth double acts of the 80s, from Soft Cell to Erasure, but again, they’re not landlocked in that decade.

Later phases – house and techno-pop in the 90s with Gratuitous Sax & Senseless Violins, neo-classical chamber pop in the 00s with 2002’s Lil’ Beethoven – were just that: stop-offs on a journey without a destination.

Hippo hippo shake

Their latest album, Hippopotamus, is as far from career-coasting tedium as you could get. Rather, the rule for these 15 quirkily constructed songs about sex positions and giddily excited cities would appear to have been to find things that had never been written about before, and to fashion them into entirely novel shapes. But why Hippopotamus?

“There was something really appealing about the word,” offers Russell, his accent somewhere between the West Coast and Weimar Germany. “It conjured up a lot of things, but also nothing. We just liked the image.”

Sparks have long been putting the “art” into the charts, from This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us and The Number One Song In Heaven to When I’m With You and When Do I Get To Sing “My Way”, and the cover to Hippopotamus shows a hippo in a swimming pool, as Ron and Russell look on askance.

Sparks are the surreal McCoy.

“We wrote the music first,” explains Ron in a slow drawl, “and we tried to think of a title that was as eccentric as the music sounded. It was just such a cool-sounding word; an exercise in surrealism. There is no narrative or final point to it. It just is.”

“Someone,” Russell recalls, “asked, ‘Is it a metaphor for something?’ and I said: ‘No, it’s a hippo in a pool.’”

“Sometimes,” Ron decides, “a hippo’s a hippo.”

Can’t start a fire…

After two albums – 1971’s Halfnelson, and 1973’s A Woofer In Tweeter’s Clothing – Sparks made their commercial breakthrough, five years after forming, in 1974 with their No.2 hit This Town…

And although their debut Top Of The Pops appearance was one of those stop-you-in-your-tracks affairs, if you watch it now you will be surprised at how unexceptional their apparel is: Ron in a shirt and tie, Russell wearing a brown suit and beige neckerchief.

And yet that performance remains extraordinary, as arresting as Bowie/Ronson doing Starman or Eno/Ferry circa Do The Strand; something about Russell’s alien falsetto and androgynous prancing, and Ron’s ’tache and comically/chillingly blank stare.

They still look striking today, in the shiny central London offices of their new record company, BMG.

Russell might only be wearing some regular black blazer, blue and white striped jumper and khaki trousers, his older brother Ron a black suit and matching chunky shoes, and yet something about the Maels is delightfully awry.

Russell’s corkscrew curls may have long gone but he still cuts a dandyish figure, and Ron is as sinister and strange as ever.

Meanwhile, titles on Hippopotamus include I Wish You Were Fun (about being in love with someone but wishing they were a bit less, well, dull), The Amazing Mr. Repeat (the story of a sexual acrobat so advanced he becomes a circus act), and the vaudevillian lunacy of So Tell Me Mrs. Lincoln Aside From That How Was The Play?, which typically finds Russell skilfully negotiating Ron’s demented torrents of words, the latter way too humdrum a descriptor for these far-fetched fictions.

“It’s kind of the aim of a lot of what we do,” Ron says, “either to cover topics that haven’t been addressed or things that are clichéd situations but do them in a way that hasn’t been done before.”

There are loads of songs about sex, but fewer, presumably, about sexual positions? “No, there’s not many,” Russell deadpans.

“It [Missionary Position] is sung by somebody who’s championing the conservative attitude, saying the tried and true sexual position is not to be scoffed at,” Ron elucidates.

Then there’s Life With The Macbeths, which imagines the titular Scottish king and attendant clan getting their own reality TV show, with inevitable bloody results.

Men in the mirror

Sparks changed their name from Halfnelson after their manager Albert Grossman initially proposed The Sparx Brothers, a pun on Groucho et al. Classic Pop wonders, who are the antecedents for their bizarre comic vision? Ron, it turns out, is a fan of Richard Pryor, Buster Keaton, and Andy Kaufman.

“I like the performance art aspect [of Kaufman],” he says of the comedian who died from cancer in 1984, after which there were rumours that his death was part of his routine.

“You couldn’t tell where Andy Kaufman ended and his performance began. And you can’t be 100 per cent certain that he died of cancer or whether that was part of his performance, too.”

We discuss the way David Bowie succeeded in “incorporating” his death into his work (his albums and videos) towards the end of his life. Russell said: “He did those videos that almost foreshadowed what was going to happen.”

“So few people get to define their death like he was able to do,” offers Ron. “It was pretty amazing.”

To what extent are Ron and Russell fictional constructs, and when Classic Pop leaves this interview they’ll revert to their normal selves?

“Now,” Ron says of the artificial set-up that is the interview. “We don’t feel like it’s us. We feel more ‘right’ when we’re onstage or recording. People like Bowie or Morrissey seem more equipped to be able to follow through on their stage personae. Out of necessity we have to speak about what we do, but we don’t feel that we properly present it because we’re not larger than life.”

- Read more: Making No.1 In Heaven

Classic Pop begs to differ. If the Maels walked out of BMG, our estimation is that they would stop the traffic. “That,” Ron argues, “is a physical appearance thing, not a persona thing.”

“Our music and what we do onstage and what you see on our album covers speak better about us than us telling you, the journalist, about ourselves, if that makes sense,” Russell adds. “That’s our feeling. Maybe you feel differently.”

“Maybe,” Ron ventures, “you’re really impressed.”

Who wouldn’t be? Sparks have been making brilliant, mordant, pop-operatic music for five decades and are always evolving – Sparks’ albums are all completely different, and all exactly the same.

“We work in sonically different ways [on each record] and, obviously, the personnel changes, but as far as our sensibility goes, that’s always there,” Ron considers. “Whether we’re doing electronic things or band things or orchestral things, there is a thread.”

Of all their peers over the years – first Janis and Dylan, then Bowie, Ferry and Cockney Rebel, then the likes of The Human League and OMD, then the 90s alt-rocker fraternity – which did they feel most comfortable with?

“We rarely look backwards,” Russell avers. “That’s what makes what we’re doing vital and fresh-sounding, from our perspective. We don’t look at those past decades and go: ‘Oh, if only we could find the magic we had with Giorgio Moroder’ or ‘what was our mindset when we wrote This Town…?’ We don’t reflect back on our past, so the question of what era are we really from? We feel like we’re now…”

But, if they had to spend the evening in a room with a bunch of their peers from the dim and distant, which would they pick?

“The one basic problem with that is we’re not very good at speaking with musicians,” Ron parries.

“In any room,” Russell finishes his sentence. Finally, he admits: “I’d rather be in the room with Bowie and Ferry etc. That would be more appealing than the other persons.”

How about Sparks? Where do they believe the general public would position them? As an early-70s band? A late-70s one? An 80s act or 90s?

“It’s really odd,” Russell notes, “because it depends which country, and which age group, you ask.”

Good point. Sparks enjoyed two periods of success in the UK: 1974-5 and 1979, after which they had hits (notably When I’m With You) in the early-80s in France so big they became household names, in the mid-80s they finally became prophets with honour in their own land when Cool Places from 1983’s In Outer Space broke into the US singles chart, while When Do I Get To Sing “My Way” became Germany’s top airplay record of 1994.

- Read more: Sparks 2020 interview

To keep things nice and circular, 2002’s Lil’ Beethoven became a massive critical success in Britain and almost relaunched them here. Sparks have a habit of remodelling themselves, and people love them for it.

“Sometimes, we get in a taxi in London,” says Russell, doing a terrible impression of a cockney cabbie, “and they’ll be, like, ‘Aren’t you, er, Top Of The Pops, right?’”

Ron tells a story about being recognised recently as he attempted to pass through Immigration on his way from Paris to London on the Eurostar. Suddenly, the ratty, bored staff went from sour to starstruck.

“They were incredibly nasty, then all of a sudden one of them went, ‘Aren’t you?…’ Suddenly they changed into these fanboys. That was almost more offensive.”

The fame game

Fame for the Maels is a necessary part of the business of making radically entertaining pop. As they say: “We don’t hang out normally – or ever.”

They reveal nothing about their private lives. Ron does admit that he and Russell live 10 minutes from each other in LA, that Ron drives a 1974 Volkswagen camper van based on a German military vehicle from World War II while Russell has “gone socially conscious” and owns an electric car (a BMW i3).

Ron used to live in a high-rise apartment about 10 years ago, and Joe Walsh of LA rockers the Eagles lived on the top floor. Oh, and he goes for a daily walk with Brian Wilson – he doesn’t arrange to go walking with him, he just happens to be there at the same time.

Apart from that, though, little is known about the mysterious Maels. “That’s good,” Russell suggests.

The last time Sparks were interviewed, it was in 2015 for FFS, their collaboration with Franz Ferdinand. There were some rumours of tensions behind the scenes, and of clashing egos. Are the Maels relieved to be back on Terra Sparks, as it were?

“That was a valuable experience and musically we felt it was strong and allowed Sparks to also be able to reach another audience that weren’t maybe that familiar with the band so that was beneficial,” Russell says, diplomatically.

FFS hasn’t been the only extracurricular project they’ve been involved in: there was 2009’s radio musical/pop opera The Seduction of Ingmar Bergman, and more recently they have been working on a musical with French movie director Leo Carax.

“It’s liberating,” Russell says, “to be back doing what is more natural to us, working within the pop format.”

For Sparks, pop is not dirty, it’s a beautiful word. “We’re really fortunate to be able to do exactly what we do, which is three- and four-minute songs,” Ron furthers. “We don’t see pop music as a means to be doing an artistic statement. We just like doing pop music.”

Not for Sparks the mature reflections on mortality and dread you might expect from musicians aged 68 (Russell) and 71 (Ron). Hippopotamus is more wayward than that. Ron’s latest songs – whether they’re about Scandinavian design or a town where all the inhabitants are beside themselves with glee – do address the usual love, life and the human condition; they just do so obliquely.

And yet it’s Sparks’ very idiosyncrasy that means they’re not taken as seriously in some critical quarters as they might be.

“You get the sense that if something has a humorous tinge to it, it’s not perceived as having depth and substance to it,” Russell notes.

“A songwriter can talk about ‘she left me and now I’m all alone’ and that sort of thing is seen as more sincere and honest, but if you talk about a relationship [like the one in I Wish You Were Fun] in terms of, ‘I like this woman, but goddamn I wish she was more fun’ – that’s not ‘honest’.

There has always been the perception that humour means the song is more frivolous, less ‘authentic’.

“We could never figure that out,” he continues. “That if you’re from Laurel Canyon [home of the early-70s winsome troubadour] or an indie guy just strumming and you wear street clothes while you’re singing, that’s more authentic than someone who dresses up and presents issues and themes in a different way.”

Forget the naysayers: Sparks are true originals: iconoclasts, conceptualists. “It’s conceptual because what we do is pretty stylised both musically and visually,” Ron agrees.

“But we’re not like painters where this is some performance art piece and we’re going to step outside and do something else some other time.

“As much as we can be, we’re really sincere in what we’re doing.”

It’s sincerely contrived?

“In order to express that sincerity, there has to be an element of contrivance, as a means to deliver that sincerity,” he allows, finally, preparing to step out into the sunshine and stop London traffic.

“But it was never about seeking a lifetime career. We started out as musicians following a passion. It’s so far beyond a shock to us at this point that we’re still doing it.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!