Madness interview: “We’ve collided together in a sandpit of joy on this new album”

By John Earls | March 8, 2023

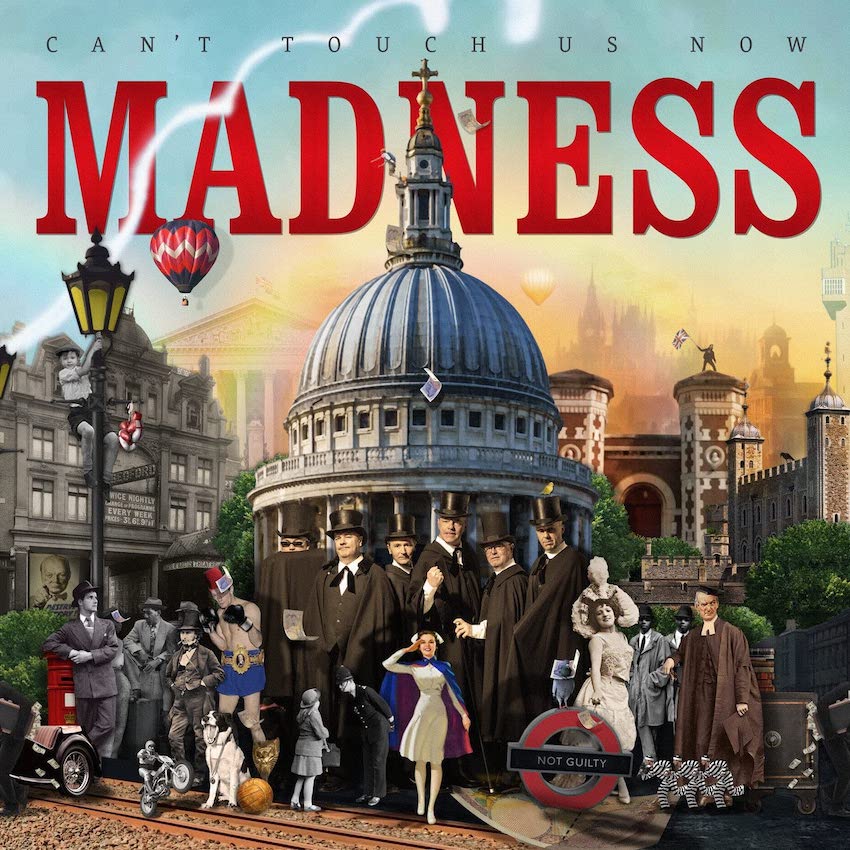

No longer a nostalgia band, Madness have spent the past two decades assembling “new universes” of music to showcase their impeccable knack of knowing what makes people tick. In 2016, as they released their 11th studio album Can’t Touch Us Now, we caught up with them…

When Madness launched new album Can’t Touch Us Now, they wanted to highlight just how much of a long-running institution the band are.

Others might be more prolific – Can’t Touch Us Now is only the 11th album of a career that began 37 years ago with 1979’s One Step Beyond – but few are more universally loved.

In August, a survey of the dream festival line-up saw Madness in the Top Ten, coming ninth, sandwiched between David Bowie and Rihanna. Such is the eternal power of their show, Madness were – alongside Rihanna and Eminem – the only act still going in that Top Ten.

That album title is a statement of intent, but initially it seemed undercut by Madness’ choice of how they settled on showing their venerable career: by having a press conference at Chelsea’s Royal Hospital with Chelsea Pensioners taking the role of journalists and asking the questions.

“God knows how we came up with that particular concept,” admits Suggs. “It must have been in the pub.” That wouldn’t be a surprise – Suggs meets Classic Pop at London pub venue The Slaughtered Lamb, and Madness are still capable of out-drinking most other bands.

But there was, however unintentionally, a wisdom to getting the Chelsea Pensioners’ seal of approval. “I’ve never met such a bunch of characters,” Suggs enthuses.

“We were trying to find an institution older than Madness for the album launch. The only other one we could think of was The Rolling Stones, and we didn’t want to do a press conference with them.”

The singer admits that, until he met the Pensioners on the day, he wasn’t entirely clear what the charity is all about. “I thought they might have been veterans of the Boer War, until someone pointed out that was 200 years ago.

“Even World War I, which was my next-best guess, is too long ago now. Actually, the Chelsea Pensioners is for ex-soldiers with no wives or children. It’s a fabulous community, full of very interesting people who happen to be old. That was a great afternoon.”

Madness’ main ethos is to strengthen the idea of community spirit.

From the loving family memories of Our House via the shared rites of passages detailed in Baggy Trousers and House Of Fun to the trials of middle age on 2012’s previous album Oui Oui Si Si Ja Ja Da Da, Madness are about music that brings people together – and that’s one of the main reasons they’ve lasted so long.

“We can’t change the system, unfortunately,” says Suggs with a wry smile. “But our band has always been about community and co-operation. That’s all we can do – keep going on about those ideas.”

Madness may not be associated with being overtly political, but that would be to ignore the anti-racist message of Embarrassment or how their initial career ended in 1986 with the elegiac anti-apartheid (Waiting For) The Ghost Train, their final message before splitting for six years.

Since their comeback, Misery has been a neat summary of Madness’ determination to celebrate life despite the state of the economy.

It’s there, too, in Mumbo Jumbo on the new album. It may have been written before Brexit, but the song adroitly skewers both politicians seeking to divide the nation and their determination to avoid inconvenient facts.

“We’re in chaos as a nation, aren’t we?” rues Suggs. “Mumbo Jumbo is, as the title says, about the mumbo jumbo we’re being fed as people. I don’t really know where this chaos is all going to end up, and it is worrying.

“On a song like Mumbo Jumbo, all we can do is try to filter our thoughts about the state of the country into some kind of sense.”

But it’s important to note that Madness are experts at not making such statements preachy – because such an empathetic band are happy for the listener to figure out a song’s message themselves.

- Read more: 13 of the best Madness songs

“We’re like Chic, in a way,” Suggs explains. “Nile Rodgers says Chic’s music has HDM: hidden deeper meaning. That’s the story of our career, too, that we’ve always got a hidden deeper meaning. And we’re happy for it to be hidden, because you don’t want to shout about your meaning.

“People aren’t stupid. People get patronised enough as it is without us patronising them, too. We know that, however people are portrayed, they’re not stupid. And the fact we appreciate that is one of the big reasons we’ve continued, I’m certain of it.”

Suggs admits there was some debate about having a statement as seemingly arrogant as Can’t Touch Us Now as the new album’s title, but the band eventually agreed it was time to remind people of Madness’ status.

It was, Suggs says, initially just going to be the name for their latest annual Christmas arena tour, based on saxophonist Lee Thompson’s new song of the same name.

“When Can’t Touch Us Now was suggested for the tour title, I thought ‘Well, that’s just funny,’” Suggs recalls. “As for an album title, though? That’s more permanent, and you do think ‘Does that sound a bit too arrogant?’

“But Madness have got to a point now where we sold 20,000 tickets for our House Of Common festival at Clapham Common, and we did that with no sponsorship or branding. I’m aware the band have had as many downs as we’ve had ups.

“But we’re at the point where we’re outside of the boundaries of whatever the music industry is called these days. So let’s celebrate that – and let the title also be a celebration of anyone who’s escaped the confines of what’s expected of them.”

Exceeding expectations is something shared by all of Madness, and helps explain why community is so important to the band. Because none of their childhood family life was exactly regular.

Suggs’ father William McPherson was a heroin addict. Lee Thompson’s father was in and out of prison, with the future saxophonist part of an infamous teenage graffiti gang in North London with pianist Mike Barson.

Drummer Dan Woodgate was brought up by a series of nannies after his parents’ divorce. Singer/dancer Cathal Smyth rarely stayed in the same continent for long, thanks to his father’s job in the oil industry.

As Suggs says: “Most of us come from very dark backgrounds, and that doesn’t go away. Because we didn’t have a sense of community as children, we had to learn it in Madness.

“The band taught us how to be fair to each other and how to communicate with other people. That’s not the easiest thing to learn, especially in the madness of our popular culture.”

If it was hard for Madness to find their way together as young men from dysfunctional backgrounds when the band formed in Camden in the late 1970s, that chaos has never really left them.

They seem to perfectly fit the industry adage that musicians essentially remain the same people as when they first find success. You don’t have to look too hard to find the bolshy, up for it perma-partying spirit of lads in their early-twenties when it comes to Madness.

Getting them in a room together for promo is an impossible task, and even trying to pin one of the band down can be tricky.

When they do get together for shows, the catch-ups can be long, liquid and full of adventure – anyone who’s seen Madness at a festival knows it’s never going to be a staid, sober run-through of the hits.

They still push the boundaries of pop music, and the six men currently in Madness still explore life’s possibilities to the full, too. It’s why the idea of them being national treasures faintly appals them.

“We’ve still got chaos,” insists Suggs. “National treasures? No thanks. If you saw the reality of what goes on behind the scenes in Madness, we wouldn’t be allowed near anything called an institution. We should be institutionalised.”

They are at least each other’s own surrogate families, with all the arguments that involves. Barson was the first to bail, his departure in 1984 soon leading to Madness’ split in 1986. They reformed in 1992 for the first Madstock concert at Finsbury Park.

- Read more: Making Madness – The Rise & Fall

But, once they began trying to record again, tensions really began to show. Guitarist Chris Foreman left after working on their second reunion album, 2005’s covers set The Dangermen Sessions.

Bassist Mark Bedford stopped touring for three years and wasn’t involved on Oui Oui Si Si Ja Ja Da Da. And now Cathal Smyth has left, bailing in 2014 to make his first solo album, the surprisingly contemplative A Comfortable Man.

Foreman and Bedford eventually rejoined, which suggests Smyth’s departure is probably temporary. Suggs is every bit as companionable as his public image suggests. But talking about Smyth’s departure is the only time he becomes even remotely frosty in our interview.

“Cathal is still on sabbatical at the moment,” he starts, his words suddenly slowing down. “He made his solo record during the time we were recording our new album and I really don’t know if he’ll come back. I know you have to ask the question about him, but it’s not something I feel comfortable talking about.”

A rare pause, while Suggs tries to consider how to sum up Smyth’s current status.

“This band is a very complicated entity. It’s a dysfunctional family, and within that you’re going to get dysfunctionality. But nothing is unresolvable, and the seven of us have always had tolerance and love for each other.”

I suggest that the only way in which Madness would really be in trouble is if Woodgate decided to leave, however temporarily. It’s an idea that causes one of Suggs’ frequent convulsions of delighted laughter.

“Woody leaving? Yeah, that would be like the ravens leaving the tower. Me and him are the only two never to miss a Madness gig. Woody explained to me why once.

“Before Madness, he was in a band called Fat. Woody took a week off, so they get another drummer in – and they never asked Woody back.”

So Madness, even if they’re currently down to a six-piece, are unlikely to split again any time soon. But is it telling that the full chorus of the title track of Can’t Touch Us Now is “You can’t touch us now, we’re in too deep”?

Is being in Madness like the Mafia, that you’re simply not allowed to leave? More Suggsian laughter.

“Well, to my mind, it’s that the British public are in too deep with us. I think we are wanted. Whatever happens, Madness can go off and come back. Can’t Touch Us Now is released by Universal, but that’s the first time we’ve had a record contract since The Dangermen Sessions.

“We can organise everything ourselves, and we’ve created a depth of culture over the years that means we are in deep with the public.”

It helps that, as Suggs puts it, Madness escaped “Eighties nostalgia shit” with the release of 2009’s album The Liberty Of Norton Folgate.

A loose concept album about the Norton Folgate micro-suburb of East London that officially doesn’t come under government control, it was Madness’ first album of new material in a decade and garnered the best reviews of their career.

The following Oui Oui Si Si Ja Ja Da Da was, by contrast, just trying to write great songs. It, too, was a triumph.

“We put a fuck of a lot of effort into Norton Folgate,” Suggs explains. “We thought that might be the last record we’d make and, if it was, we wanted it to at least be one we could be proud of. It opened the door for us to escape being seen as a nostalgia band, and Oui Oui was very well received, too.

“We feel like we’ve been given an opportunity since Norton Folgate and the feeling is ‘Fuck it, let’s just try to plough on.’ We’re a working band again now, so it’s up to us to just do what we do, which is obviously making records.”

Is that easier said than done in such a dysfunctional family?

“It’s not so bad. We’ve all stopped farting about a bit and concentrated again. So this new record was a relatively painless process. The mad members are less mad, the sane members are less sane and we’ve all met in the middle somewhere. We’ve collided together in a sandpit of joy.”

There is, loosely, a concept to Can’t Touch Us Now, despite Suggs’ reluctance to call it a concept album. “On Oui Oui, my lyrics were more abstract than usual,” he explains.

“I’ve concentrated on getting back to the narrative side of my songwriting. I wanted stories again. All the songs are about specific people or events, and I’m telling those stories.”

Following the uptight anti-hero of first single Mr Apples, the album also depicts a stern would-be father-in-law on Herbert, the gadget-obsessed wideboy in Another Version Of Me and Pam The Hawk: “A beggar – if that’s the correct term, I don’t know what the modern vernacular is. But Pam was an amazing character; she’d make £200 a day before she unfortunately passed away.”

Following the uptight anti-hero of first single Mr Apples, the album also depicts a stern would-be father-in-law on Herbert, the gadget-obsessed wideboy in Another Version Of Me and Pam The Hawk: “A beggar – if that’s the correct term, I don’t know what the modern vernacular is. But Pam was an amazing character; she’d make £200 a day before she unfortunately passed away.”

Having written about Amy Winehouse in Circus Freaks on Oui Oui Si Si Ja Ja Da Da, Suggs writes about their final meeting on moving ballad Blackbird on the new album.

Winehouse lived in Camden, near Suggs, and he still despairs at her death five years on.

“I saw Amy on Dean Street in Soho very shortly before she died,” he sighs. “So soon after her death, the timing wasn’t right to write about it on Oui Oui. But the experience kept going round and round in my head. She was walking towards me and went ‘Alright, Nutty Boy?’

“That was just so funny, because no-one had called me Nutty Boy since 1979. I’m a 55-year-old man, for goodness’ sake. The way she said it was very funny, too, and I felt it captured something about her. I mean, what can you say about Amy that hasn’t already been said?

“But I felt compelled to write Blackbird, and Chris wrote a very nice soul motif that immediately fit the lyrics. That song came out very naturally.”

Winehouse was a regular at The Dublin Castle, the Camden pub where Madness played their first shows and where Suggs still goes drinking 40 years later.

It’s one of the few pub venues in London where new bands can still get a gig easily – a problem for new musicians that appals Suggs.

“When Madness started, there were six or seven pubs in Camden alone where you could get a gig,” he says. “There’s a chapter in Chrissie Hynde’s book where she writes about coming to London back in the mid-70s, how it was absolutely made for musicians: there was cheap public transport, you could go on the dole, you could squat and you could find an abandoned warehouse to rehearse in.

- Read more: Top 20 posthumous pop releases

“Now? Fuck, try going on the dole now. I know Henry Conlon, who runs The Dublin Castle, and he says the energy a new band needs just to keep going now is massively harder to maintain.

“The Dublin Castle doesn’t charge, but a lot of pubs make bands stump up £200 before they’ll let you play. When we started, you were alright so long as you brought enough people to buy a couple of pints.

“And, of course, bands can’t afford to live in London anymore anyway. You have to be an Etonian to become a fucking musician nowadays, or get mummy and daddy to pay for you. I really do worry for new bands.”

The new album’s other concept was simply to get the band writing together again, rather than have everyone come in with complete songs written on their own.

“Our management noticed that, during Oui Oui, we were getting more and more individual,” Suggs admits. “We weren’t collaborating with each other so much to write songs, and we were aware a lot of our classic tracks were co-writes.

“That’s quite abstract, in a way, as songs are just songs. But we’ve all made a conscious decision to collaborate more.”

Along with Suggs, it’s Barson and Thompson who’ve been the main protagonists of Can’t Touch Us Now, but the singer insists: “If Woody, Mark or anyone else has a tune, I’ll try to write with them.”

Suggs’ reticence to classify Can’t Touch Us Now as a concept album is mostly down to the fact that the characters he’s writing about aren’t linked. “I was never into concept albums,” he tuts. “There’s a contrivance to them, and you end up wedging songs onto them for the sake of the story.

“You have to ram songs in, and that rarely works. Look at Tommy by The Who. There are some great songs on there, but there are also some real duff ones.”

Madness first tried to write a concept album on 1982’s The Rise And Fall, but Our House is one of its few songs to fit the intended theme of childhood. And Suggs would also argue against The Liberty Of Norton Folgate qualifying.

“There was a very clear remit on Folgate, of it being an ode to London,” he considers. “But, as Chris pointed out, ‘What the fuck are the rest of our songs about, then?’ So Folgate is hardly a concept, really. Maybe we’d do something more concrete like Folgate again, but I don’t know if we’ve got a concept album in us.”

Like Oui Oui, the new album was recorded at the infamous Toe Rag studios, the back-to-basics base in Hackney where The White Stripes laid down their breakthrough 2003 album Elephant featuring Seven Nation Army.

Owned by producer Liam Watson, it features entirely analogue equipment and eight-track recording equipment.

Watson worked with Clive Langer, the producer who has overseen all 11 Madness albums. “All the effort has gone into writing this album and the rehearsing of 25 potential songs,” explains Suggs.

“Doing that meant that actually recording it was as painless as possible – it only took three weeks. Having only eight tracks to play with really does focus the mind.

“We took the album to Charlie Andrew, Alt-J’s producer, for some technical wizardry in mixing afterwards. But what we wanted was to capture the feel of a Madness performance. Once you write a good song, all you really want to do is to arrange it and rehearse it well, so that it’ll sound good on the album.

“To do that, you should do 15 or 20 takes of it in the room together, just performing it until you’ve practiced it enough. That’s what we did on this record. You capture something more than the modern method, where you lay down the bass, then the drums, then the guitars…

“Even if there are bumps and bruises, you just know immediately if a particular take has got a certain atmosphere. Capturing the spirit of our shows is really what has excited the band all along.”

Whatever the reception that meets Can’t Touch Us Now, it leaves Madness in rude health. As a working band, it shouldn’t be too long before album 12 arrives.

They may still play those songs of young men – last time Suggs spoke to Classic Pop, he admitted that the line “Sixteen today, and up for fun” in House Of Fun is “an albatross, Madness’ very own ‘Talking about my generation’.”

But they’re still able to play those songs with an exuberance of a band aware of their good fortune that, dysfunctionalities and all, they essentially still get on.

So will Madness still be playing It Must Be Love when they’re as old as Chelsea Pensioners? “I hope so,” says Suggs, after another burst of laughter.

“If we get to have the lives they’ve had, then fantastic. When I think about old people playing pop music, I don’t think about The Rolling Stones.

“I look at Buena Vista Social Club, where it’s possible to play pop music with some dignity. You don’t have to flounce about in leather trousers, all winks and glitter.

“If you still enjoy making pop music – which we most assuredly do – and you feel there’s some go in you, that’s the main thing about deciding whether or not to carry on.

“If you still enjoy making pop music – which we most assuredly do – and you feel there’s some go in you, that’s the main thing about deciding whether or not to carry on.

“Our job as a band is like reggae and soul artists who don’t have a miserable bone in their body or their music, despite the shit they’ve been through. It’s about trying to make the effort look effortless.”

And Madness, Suggs believes, have quietly become as big as they were during the Baggy Trousers days. Their albums chart better than ever, they sell more tickets than ever.

“Every year, Madness opens out in a different way than I thought it would. It’s getting bigger every time, and it’s starting to get scary because none of us knows what we’re unleashing. I don’t want to end up a gigantic popular rock star, but it’s heading in that direction, for some peculiar reason.”

Making great records and still playing celebratory shows must have something to do with it?

“You’re very kind! When we go on stage, I do feel a great deal of pride in the fact that we’re a pretty fucking good band. We’re one of the three best live bands in the world. And I don’t know who the other two are.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!