The story of Creation Records

By Classic Pop | March 7, 2023

Classic Pop recalls the history of Creation Records, the label that dominated the indie-pop landscape in the 1980s and 90s… By Paul Lester

Classic Pop recalls the history of Creation Records, the label that dominated the indie-pop landscape in the 1980s and 90s… By Paul Lester

The 80s and 90s were a golden age for independent record labels – Postcard, Factory, 4AD, Mute, Rough Trade, ZTT – but of all of them, arguably the one that most successfully straddled the two decades was Creation.

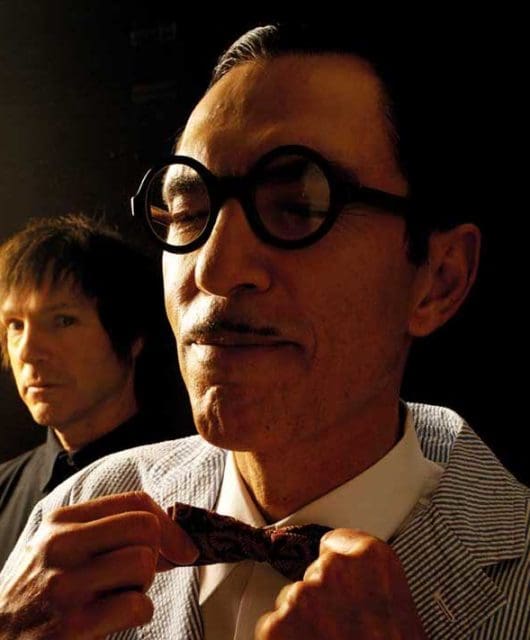

It was an auteur project from start to finish – it was founded by Alan McGee (with a little – well, a lot of – help from Dick Green and Joe Foster) – and, in a way, it was his record collection, his crazed dreams and obsessions, writ large.

It soared and crashed as McGee rose and fell himself. It both reflected the developments of the period and effected changes, including as it did in its relentless release schedule some of the landmark records of its time – of any time – culminating in the epochal 1991 triptych of Primal Scream’s Screamadelica, Teenage Fanclub’s Bandwagonesque and My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless; three albums that define indie ambition forever.

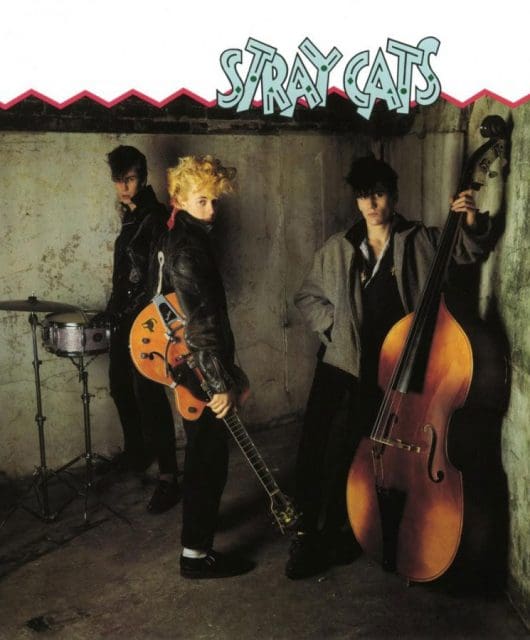

It began as a cult concern, the meeting place for all manner of eccentric waifs and strays – The Legend!, Momus, Lawrence (Hayward) of Felt – but even at its most esoteric and extreme, Creation struck a chord, bending the populace to its will through the wayward but appealing pop of The Jesus And Mary Chain, The House Of Love, Ride, Sugar, Boo Radleys and Super Furry Animals.

At various points, it was the de facto home of C86 “cutie”/jangling guitar music (The Jasmine Minks, The Bodines, The Weather Prophets), the label that gave us shoegaze (Slowdive, The Telescopes, Swervedriver), the birthplace of acid house/indie–dance and, somehow, the HQ of the biggest band in Britain, if not the world (Oasis).

“It was a random collection of misfits, drug addicts and sociopaths,” Pat Fish of The Jazz Butcher proclaimed at the start of the documentary, Upside Down: The Creation Records Story.

For Bobby Gillespie, the Primals mainstay to whom the film was dedicated, Creation was full of “outsiders, chancers and lunatics”.

McGee admitted: “I do seem to attract, or am attracted to, nutjobs.” As for Joe Foster, summing up this revolutionary imprint, he said: “It started as our grand delusion, and eventually became the mainstream sound of a generation.”

Creation literally began in a – or rather, The – Living Room populated by a few dozen likeminds and grew and grew until, within 10 years, its flagship band would inspire half a million believers to congregate in a field in Knebworth, Hertfordshire.

According to Glaswegian McGee, the pivotal moment in the creation of Creation came with his decision, in 1980, to come to London and attend an indie night in Victoria where he saw The Television Personalities, the first band to blow his mind since The Clash.

He recalls seeing sometime member Foster onstage, sawing a Rickenbacker guitar in half. McGee was sufficiently moved to traipse to record store Rough Trade the next day and buy all their records.

“I thought, I can do that,” McGee said of Dan Treacy’s maverick mob. “That’s when Creation Records became a reality – without them, there would be no Creation.”

McGee began promoting gigs in 1981, when he was 21. He launched The Living Room at The Adams Arms in Central London and it became the club for indie cognoscenti searching for a new scruffy little underground to counterbalance the glossy, glamorous pop and new romantic happening overground.

In 1983, McGee quit his day job at British Rail to launch Creation with Foster and associate Dick Green. Their first releases – by music writer Jerry Thackray aka Everett True alias The Legend!, The Revolving Paint Dream, The Jasmine Minks and McGee, Green and Foster’s own part-time combo Biff Bang Pow! – were variously peculiar, psych-inflected and scratchily melodic, i.e. of niche interest.

But there were early signs of a broader commercial potential in The Loft’s Why Does The Rain? from September 1984 and the extreme noise pop of The Jesus And Mary Chain’s Upside Down from two months later.

“They had the sound, the image and the philosophy – everything was intact,” said Gillespie of East Kilbride’s feedback scions.

McGee was initially unimpressed, but before long he was frothing at the mouth and proclaiming that, together, the Mary Chain and Creation were “going to make millions!”

“It was a brilliant, violent, pop record,” McGee said of Upside Down. He assumed it would be “a big No.1 hit” in the vein of The Ronettes’ Be My Baby (the Mary Chain’s Reid brothers’ avowed intention was to combine garage noise with girl group harmony).

- Read more: The story of Rough Trade

And although it didn’t quite manage that, it did make the band arguably the most notorious since the Sex Pistols (give or take the concurrent Frankie Goes To Hollywood), helped not a little by the riot at their incendiary (and brief) performance at North London Polytechnic.

“This is truly art as terrorism,” declared McGee afterwards, although the band had to take refuge in their dressing room as fired-up audience members pounded on the door with hammers.

Suddenly, Creation offered an alternative to the cosy mainstream pop consensus provided by Live Aid.

From their office – little more than a broom cupboard, really – in Hatton Garden, they set themselves up as the standard bearers of rock’n’roll degeneracy, their ethos encapsulated by Primal Scream, fronted by sometime Mary Chain drummer Gillespie, who seemed to embody, with his Roger McGuinn fringe and pale, skinny frame, every dissolute leather-clad rocker there had ever been.

Creation’s first heyday came with the gorgeous Byrdsian jangle-pop of the Primals’ All Fall Down/ It Happens and Crystal Crescent/ Velocity Girl, The Bodines’ Therese/ I Feel, The Loft’s Up The Hill And Down The Slope, The Weather Prophets’ Almost Prayed and The Jasmine Minks’ What’s Happening and Cold Heart – together they were a beacon of lustrous indie in that dead zone between the demise of new pop and emergence of acid house.

But with the Mary Chain signed to Warners subsidiary Blanco Y Negro, Creation didn’t yet have a hit act, one that could sustain their mad misadventures.

Nor did they have one that the press could blazon as radically affecting a break with the past – for all the greatness of their releases to date, they had mainly been glorious upholders of rock tradition rather than signposts to a bold new future.

Enter, circa 1987-88, The House Of Love and My Bloody Valentine. The debut House Of Love album signalled a change for Creation. It had that inimitable hazy sound typical of Creation, but it also had well-formed, memorable songs such as Christine and Man To Child.

Not surprisingly, that self-titled debut gave Creation their first chart entry (albeit at No.49) and caused the phone to ring off the hook, with major labels wanting in on the action. More people were employed at Creation HQ, and there was more of a party atmosphere, which suited the band.

“They were absolutely rock’n’roll animals who put it on that they were mummies boys,” said McGee of THOL, who boasted a Morrissey & Marr-style writing partnership in frontman Guy Chadwick and mercurial guitarist Terry Bickers and had about them a deceptively austere air.

“I went on tour with them and theirs was the worst behaviour. They were shockingly out of control,” McGee said of Chadwick, who liked a drink and admitted he “couldn’t cope with fame”, and Bickers, who was soon suffering from nervous exhaustion combined with drug psychosis.

Read more: The story of Spike Island

Despite the mania, McGee managed to secure THOL a deal with Fontana, one of many majors in awe of the ginger Scot’s A&R foresight.

As for My Bloody Valentine, long dismissed as fey janglers, they seemed to dramatically metamorphose overnight.

They issued the seismic You Made Me Realise EP, which single-handedly changed the sound of the electric guitar and, as per Jimi Hendrix before them, offered a whole index of possibilities for the tired instrument.

The subsequent Feed Me With Your Kiss EP and Isn’t Anything album confirmed MBV mainman Kevin Shields as the premier guitar/studio sorcerer of his generation.

“They went up about five levels with Isn’t Anything,” said Bob Stanley of Saint Etienne, who were managed by McGee and later signed to the label.

Isn’t Anything made Creation the natural home for aspiring “shoegazers” – the term ascribed to musicians fixated on the fx pedals at their feet.

Ride, The Boo Radleys, Slowdive, The Telescopes and Swervedriver (who were a sort of UK take on America’s Husker Du/Dinosaur Jr/ Sonic Youth axis) all signed, with Oxford’s fab four, fronted by the luscious-lipped Mark Gardener, deemed the ones most likely to achieve mainstream success with that drone-pop sound. Indeed, Ride’s second EP, Play, became Creation’s first Top 40 entry in April 1990.

Meanwhile, since 1987-88, acid house had been raging (or rather, raving) across Britain, but its ethos – its beats, loops and attendant ecstasy-fuelled smiley culture – had yet to infiltrate Creation.

That eventually happened in 1989 when, bored at an indie club in Manchester, McGee and crew decamped to the Hacienda, where he had “an epiphany” as he witnessed several hundred revellers, led by Happy Mondays’ gurning totem Shaun Ryder, going “absolutely mental” to the electronic pulse of music born in Chicago and Detroit.

As a result, McGee temporarily moved to Manchester, where they had, he joked, “a better class of drugs”, and he introduced the new dance motion to Gillespie, believing it would work for Primal Scream.

Cue the February 1990 single Loaded, an Andrew Weatherall remix of an earlier Primals track called I’m Losing More Than I’ll Ever Have. According to early Mary Chain bassist turned video director Douglas Hart: “Acid house reinvented Creation; it reinvigorated it.”

It also turned Creation into the music business version of Babylon.

“That’s when it really went off the hook and the party really started,” said an onlooker of the label’s offices in Hackney, a series of mazes and staircases that became the scene of all manner of chaos.

Somehow, though, they still managed to get the job done, mainly thanks to stabilising force Dick Green.

Loaded made McGee’s dream come true: Primal Scream on Top Of The Pops, beamed into millions of homes.

It was also the record that allowed Primal Scream to truly explore Gillespie’s, and McGee’s, record collections, and their shared love of punk, dub, disco, country, krautrock, free jazz, PiL and Lee Perry, Big Star and Beach Boys, on the seminal Screamadelica, which dazzled the critics in September 1991 and was voted Album of the Year by NME.

“It summed up that whole era for a generation,” proclaimed New Order’s Peter Hook.

Within two months, Teenage Fanclub had issued Bandwagonesque – US magazine Spin’s Album of the Year and the long-player most likely to sell Creation to America – and My Bloody Valentine had released Loveless, whose protracted recording brought McGee to the brink of a breakdown and was regarded as the ultimate in electric guitar wizardry.

“It was the last great rock record,” McGee said later. “It’s all been going backwards since.”

With the Primals’, TFC’s and MBV’s respective masterpieces, Creation were higher than the sun. And yet the ever-prescient McGee could see the downer coming.

“Even though I was on a lot of drugs. I knew that this was the peak,” he said. “If it got any better it would be pretty strange.”

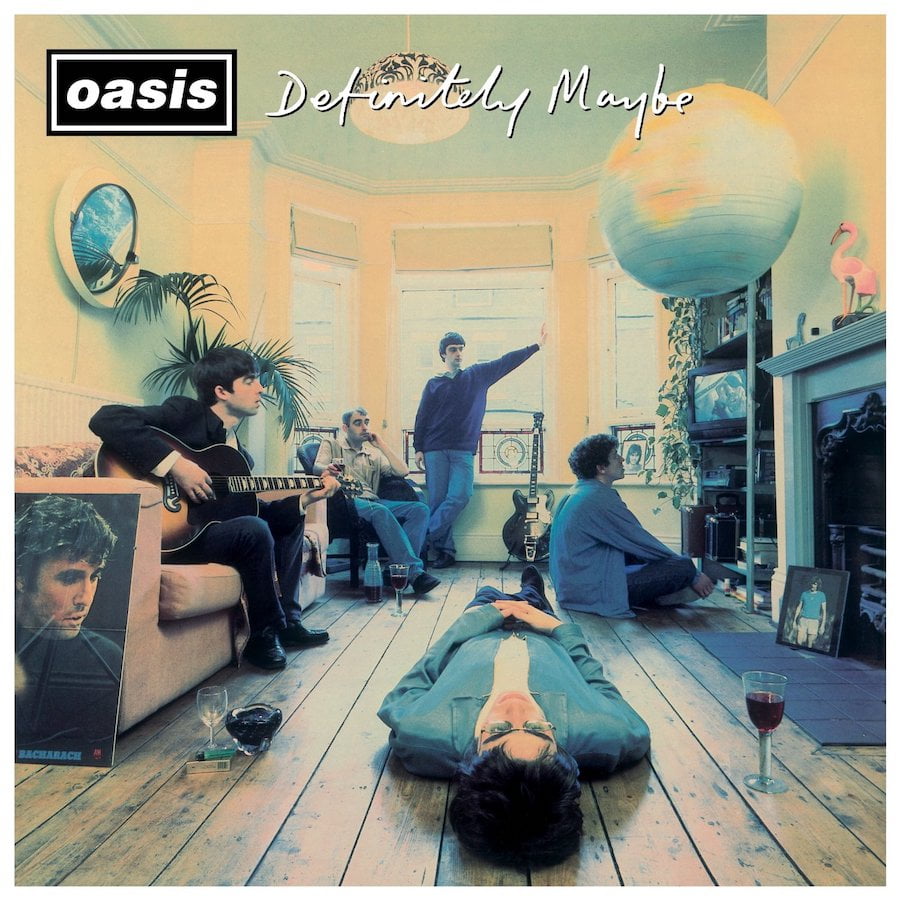

It would be hard to dispute that this was Creation’s creative apotheosis. But their commercial zenith didn’t come for another three years, following the selling of the label to Sony and subsequent arrival of Oasis.

Both events were well-timed: Creation were on the verge of bankruptcy after years of profligacy and McGee indulging his every musical whim, with rampant signings and expensive studio bills, not to mention the assorted pills, thrills and bellyaches.

“Their ambition outstripped their financial income,” said Gillespie. “They were winging it all the time.” Fortunately for Creation they had in Noel Gallagher one of the great populist songsmiths, and in his brother Liam one of the great British frontmen.

The Stone Roses may have been what the world was waiting for, in theory, but it was Oasis who put it into practice.

They were phenomenally successful and – on the back of million-selling albums Definitely Maybe (1994) and (What’s The Story) Morning Glory? (1995) – became the biggest band since The Beatles, sparking the Britpop movement.

Unfortunately, McGee largely missed the moment Creation achieved world domination because he was too busy taking drugs. “I was partying for six years,” as he put it.

He pulled himself back from the edge, only to replace necking pharmaceuticals with another mania: acquiring acts. There were, in Creation’s final days, some good signings – notably, Super Furry Animals – amid legions of dubious ones (Mishka, Ruby, Adorable, Arnold, Idha – the list is endless).

But by the late-90s Creation had become everything it despised: a corporate leviathan run as a proxy by Sony, treating music as commodity not life-changing art.

There was one final blowout – 2000’s XTRMNTR, Primal Scream’s second great distillation of Gillespie and McGee’s favourite extreme music – released just after the label was dissolved, in early 2000.

“It was unsustainable,” is Mark Gardener’s estimation of what caused Creation to crash. “There was a sense of what goes up must come down. It was all a bit bonkers. Sooner or later that catches up with you and starts to fall apart.”

Still, for 15 years or so, what McGee called “the ultimate fucked-up family” made some of the greatest records, indie or otherwise. Records that will, in the immortal words of Noel G, live forever.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!