The rise of Depeche Mode in the 80s… They came from commuterville, schlepping their synthesisers on the train to the big city’s bright lights. But soon they would be airborne and first-class, jet-setting a new pop sound around the world.

The story starts in Basildon, Essex; 30 miles from the centre of London. One of England’s new towns, developed in the aftermath of WW2, Basildon was where Vince Clarke (born Vince Martin) grew up.

After beginning his musical life on violin, Clarke took up guitar, learning the songbooks of The Beatles and Simon & Garfunkel. Playing music at Boys Brigade and church, he encountered Andrew Fletcher. The pair formed a group, No Romance In China, with Clarke on guitar and vocals and Fletcher on bass, though their name soon changed to Composition of Sound.

Basildon Boys

Early influences veered from The Cure to Phil Spector/The Crystals’ Then He Kissed Me. Post-punk alienation and pop euphoria were worming their way into Clarke’s musical mind – a man whose unassumingly shy exterior belied a big inner life.

Accompanied at gigs by a Selmer Auto-rhythm machine, they switched from guitar and bass to synthesisers. Then Clarke heard OMD’s Almost, the flipside of 1979’s Electricity. The otherworldly sounds (from a Korg) and heartfelt sentiments collided in a song that felt homemade, and approachable, unlike the glossy, remote Gary Numan, synth-pop’s first pin-up, storming the charts the same year. Synths had become cheaper and more portable. They sounded much like Basildon; new noises for a new town.

The duo next found Martin Gore, a former classmate of Fletcher’s and the owner of a Yamaha CS5. A fan of glam, early Human League and Sparks, with stints in local groups Norman and the Worms and French Look behind him, Gore had purchased the synth with wages earned working at a branch of NatWest Bank in London’s Fenchurch Street.

Synth Startup

Nearby, in the Borough, Fletcher worked at Sun Life Insurance. Clarke did various jobs, including emptying port-a-loos at airports; he soon got his own keyboard, a Kawai 100FS.

Working alone, Clarke recorded demos of his compositions, including the upbeat Let’s Get Together. But he was no frontman. They found Dave Gahan, who had mixed sound for French Look (Gore was briefly in both bill-sharing groups), and his rendition of Bowie’s Heroes impressed Clarke. The more extrovert Gahan was exactly what the group needed, a face about town, a good-looking clothes-hound (no wonder: he was studying retail display).

Well-connected, he’d been to London’s hippest nightspots, Blitz, Studio 21 and Camden’s Music Machine, where fashion and music merged. This stylish new member coined the group’s stylish new name, found in a French fashion magazine. Once they dropped the accent, ‘Depeche Mode’ (translating roughly as ‘fashion dispatch’) was perfect.

Fashion Dispatch

Clarke and Gahan shopped their quarter-inch tape demos to record companies. Rough Trade weren’t interested, but helpfully suggested Mute’s Daniel Miller. Initially unimpressed, Miller changed his mind when he saw the group support Mute’s own Fad Gadget at the Bridge House in Canning Town.

With a Boss Dr Rhythm as their new rhythm machine, the Mode were that rare thing, a magnetic live synth act. Seeing them perform in this first phase, Seymour Stein, from their US record company Sire, summed it up; “They f***ing rocked!”

Depeche Mode had other suitors, chiefly Stevo from Some Bizzare. Despite a multi-album offer from Stevo, and contributing Photographic to the label’s sampler, they went with Miller. They loved Mute’s records, especially those made by Miller himself under various guises, be it as The Normal or masquerading as electro-bubblegum outfit the Silicon Teens. Crucially, they trusted the electronic pioneer. From Miller’s viewpoint, he saw Depeche Mode as Silicon Teens made real.

Speak & Spell

Depeche just wanted to make a single. Dreaming Of Me was released in 1981, housed in a sleeve designed by a school friend. Simple and sparse, like electro-skiffle, Dreaming Of Me effervesces with pop hooks, gasping in awe at its synthesised sound.

It reached No.57, a promising position for a new act on an independent label. Then the majors came knocking, notably Phonogram’s Roger Ames, but Depeche stayed independent with Mute/Miller, achieving success with second single New Life and debut album Speak & Spell.

Potential disaster struck when Clarke quit, but it was only a momentary setback. Where others from the class of ’81 floundered, over-thinking their follow-ups (Human League) or spiralling into glorious anti-pop implosion (Soft Cell), Clarke’s departure concentrated their focus.

Smash Hits

See You emerged in January of 1982, accompanied by a Smash Hits cover. Inside, Clarke proclaimed the single to be their best yet, a gesture echoing Eno’s claim that Stranded, Roxy’s first album without him, was his favourite. The public agreed; See You became their biggest hit to date, reaching No.6.

On the group’s first Gore-written single a sing-song simplicity is nestled within a far more complex structure, almost incantatory verses and a harmonically rich, Beach Boys-style mid-section. Impressively, the song dated from Gore’s teens.

Depeche Mode were well aware of what was at stake. “1982’s the most important year. We’ll either establish ourselves with this or go to pot,” Fletcher told Mark Ellen in that same Smash Hits feature. Gahan was more assured; “We’ll deliver the goods”.

Delivering The Goods

Clarke’s replacement was Alan Wilder. Hailing from Hampstead and classically trained, Wilder answered a Melody Maker ad. Formerly of a band called The Hitmen, he easily got the job, beating an endless procession of fans and freaks.

Eager to prove they could survive without Clarke, Wilder was initially restricted to live duties. The group recorded A Broken Frame as a trio, aided by the guiding hand of Miller.

Gore’s songwriting approach involved fitting the music into the words rather than Clarke’s reverse method of shoehorning words into an existing tune. It altered the music’s spine, twisting and turning to follow Gore’s lyrical train of thought.

A Broken Frame

Leave In Silence, A Broken Frame’s opener and third single, unveils this moodier Mode. Gregorian-style chants, fat synth bass/brass and bell sounds created a gothic danceability, months before Blue Monday; much of the sonic overhaul was due to the PPG Wave, a semi-digital synth.

My Secret Garden continued the expansive melancholy, simultaneously more haunted and funky than before. Gore’s relatively lucid lyrics offered a barely veiled commentary on the group’s past, present and future (as did the album’s title).

On Monument, something perfectly constructed crumbles. With The Sun And The Rainfall, the album ends with an epic mission statement; change/rearrange.

Mood Swings

Released in September 1982, A Broken Frame received mixed reviews. This “odd, moody” album (Gahan), “our worst” (Gore) had a peculiarly adolescent charm, seeking out new identities one minute, restlessly clinging to their older selves the next, as heard on second single The Meaning Of Love and also A Photograph Of You, with the band seemingly nervous to completely move on. Despite the growing pains, they had indeed ‘delivered the goods’.

A Broken Frame hit No.8, two places higher than Speak & Spell. The exquisite cover art shot by Brian Griffin even had a top-drawer fan; Kate Bush liked the shot of a worker in the fields under a stormy sky so much that she asked the photographer to replicate it with her in early ’83.

By then, Depeche had moved on. Interim single Get The Balance Right, released in March 1983, was the first to feature their newest recruit, while the flipside instrumental The Great Outdoors was a Gore/Wilder co-write. The A-side was their most febrile effort yet; its tough rhythms and chattering synths caught the attention Stateside of techno pioneer Derrick May.

Construction Time Again

A step ahead of the synth-pop pack, they were predicting and shaping the dance revolution to come. So for the third album, Construction Time Again, Gareth Jones was enlisted as engineer/junior producer, helping out Miller and the group.

The Construction Time Again sessions took place at The Garden, studio home of John Foxx, godfather of synth-pop and Jones’ mentor. The position was clear; remake/remodel. Synths were put through amps, recorded with the acoustics of the room – and then came the samplers.

Armed with a microphone and a Stellavox tape machine, the team roamed derelict industrial sites around Shoreditch, hitting objects with hammers and drumsticks, putting the recordings into a Synclavier, a state-of-the-art sampling synth.

The Industrial Age

“We wanted to sample the world and make rhythms and melodies out of it,” explained Jones. Pipeline was the most radical example of this new aesthetic, a workingman’s blues set to a symphony of found sounds, including a train passing by.

Scavenged sounds were the perfect backdrop for Gore’s new lyrical viewpoint; worldly, politicised. Opener Love In Itself renounces romance, the sound of young men putting away childish things. More Than A Party raged at inequality.

The single Everything Counts, a No.7 hit, released in July 1983, did likewise, confronting the greed of multi-national corporations. In this masterpiece of conflict, scraping industrial noise and sledgehammer drum patterns are juxtaposed with art-rock refinement; melodica, xylophone and oboe-type sounds; rubies in the rubble.

Workingman’s Blues

Similarly, the vocals were more duel than duet, Gahan’s tough verses countered by Gore’s delicate, wistful choruses.

Dynamic contrasts like these became a recurrent motif on Mode’s records, and by now Wilder’s role had become pivotal. He contributed two compositions to the album, devising much of the sound design, developing drum patterns on the EMU Drumulator and Roland 808.

He was both a colourist, adding nuance (the unexpected jazzy chords on Love In Itself) and an alchemist, spinning their ideas into musical gold. Gore found his presence reassuring; “It was like having someone check your work before it goes out”. By the next album Wilder was the member Miller and Jones most relied upon in the studio.

Red Rockers

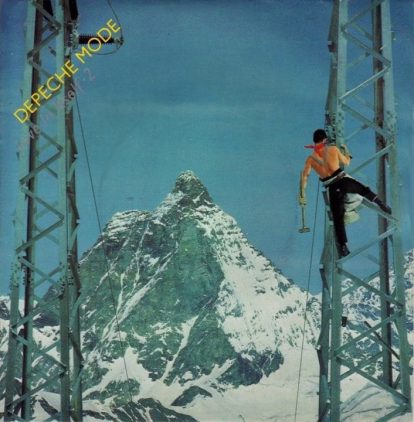

The album arrived in August ’83. Another Top 10 smash (No.6), Construction Time Again was wrapped in a sleeve depicting a Herculean worker swinging a sledgehammer atop a Swiss mountain (another Brian Griffin shot). Its bang, rattle and tinkle was hailed as a brave departure by critics.

Even the weeklies were impressed, dubbing the group “red rockers”, with NME’s X Moore calling the album “the Labour Party manifesto”. A stretch, perhaps. But mere months after Thatcher’s re-election, Depeche Mode had remade themselves and smuggled subversion into the album and single charts.

Construction Time Again was mixed at Berlin’s legendary Hansa Studios, a mecca for many since Bowie’s late 1970s masterpieces. The album also sold several times the amount in Germany than at home; unsurprisingly, the group’s fourth, Some Great Reward, was largely recorded at the same studio.

Some Great Reward

Gore was now based in the city and expressed admiration for German acts like DAF and Einstürzende Neubauten. Along with Mode’s UK labelmates Test Dept they were ‘industrial’; hard-hitting words/metal-banging music. “What we do is apply the same sort of things but in a pop context,” said Gore at the time, aware that you could get away with more that way.

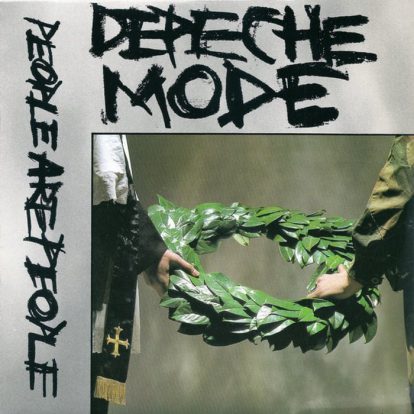

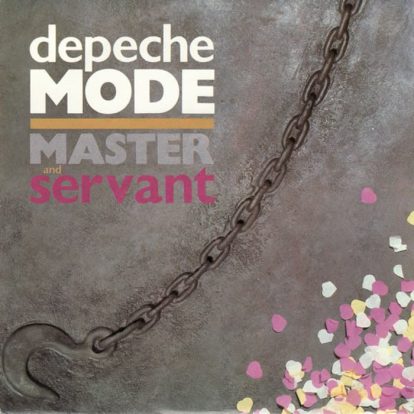

Some Great Reward took the agonising studio craft even further. People Are People’s rhythm track was sent booming around Hansa’s four-floor complex. Its mixing, as with fellow single Master And Servant, became a week-plus marathon, painstakingly crafting sonic mosaics.

Samplers returned; Emulators and Miller’s new polyphonic Synclavier captured creaking doors, rolling pebbles and gurgling water. Laughter caught by Gore on an aeroplane became part of People Are People’s chorus. They even gave the sounds names. ‘Hank’ was a snatch of acoustic guitar plucked with a coin, ‘Bucket of Sick’ was… well, anyone’s guess.

Who’s Afraid…

Mode’s sonic adventures echoed ZTT/Trevor Horn productions like Art of Noise, equally ‘maximal’ and sample-heavy (a Sarm East/ZTT studio assistant had praised Construction Time Again’s rough mixes). In that year, 1984, ZTT’s Frankie dominated the charts with a trio of singles with big themes in Horn’s big productions. Mode’s singles handled hot topics, too; religion, romance and rough sex, albeit with slightly more finesse.

People Are People, addressing homophobia and racism, was another indictment of man’s inhumanity to man; more tough/tender tension, another Gahan/Gore duel, with sampled harps gliding across beats and belches. It stormed to No.4 in the UK, hitting the top spot in Germany.

They weren’t just sampling sounds, either. Berlin’s leather/S&M clubs seeped into Master And Servant, electro-concrete strapped to a cavorting strut of a tune, the missing link between Sex Dwarf and You Spin Me Round. Hitting No.9, Master And Servant helped cement a new, darkly sexual image for Depeche, filling the ‘perv-pop’ void left by Soft Cell.

Perv-Pop

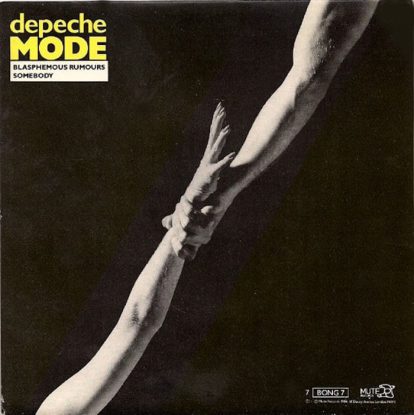

The third single, Blasphemous Rumours, questioned religion on a Top 20 hit three years before Pet Shop Boys‘ It’s A Sin. It ended with the sound of sampled breath; human music made with machines. Most human of all was Somebody, a double A-side with Rumours, sung at the piano by a naked Gore, consisting of various takes fading in and out of one another, with added loops of Berlin traffic.

It differed from Gore’s earlier love songs; this was ripped from the fabric of real experience, unlike the chocolate box contrivances of See You and others, and sprinkled in its lexicon were words such as “sick”, “perverted” and “detest”. With It Doesn’t Matter and Stories Of Old, Somebody gave Some Great Reward its soft centre. Ambivalence towards love songs remained.

“We’ll probably get slagged off for them,” Gore told Smash Hits in 1984. But he also defended the form, aware that if done authentically they could be as meaningful as those Big Topics. Elsewhere on Some Great Reward, the snaky Lie To Me made Depeche appear as synth-pop’s great sensualists, surely the first step towards Violator.

Black Celebration

Black Celebration had exhausted all those involved. Jones was gone, Miller was peripheral. Depeche’s main co-pilot this time was Dave Bascombe, Tears For Fears’ producer; big sounds with broad strokes and fine details.

Music For The Masses (a tongue-in-cheek title plucked from a classical magazine and tweaked by Gore) was recorded largely at a disused Paris cinema, where they made use of an abandoned tympani and piano; an aura of faded European grandeur hangs over the project.

Cinematic Sturm und Drang was all over the Michael Nyman-inspired arrangement for Little 15, even more so on Pimpf, where a solitary piano figure repeats, swelling to Wagnerian proportions. Much of this was down to Wilder, who had an interest in modern classical and ‘systems’ music, and whose extra-curricular project Recoil further enriched the Mode sound.

Kaleidoscope Of Sound

Even the more danceable cuts featured the same repetition and variety. Single Behind The Wheel featured a four-chord sequence, Gahan’s laconic vocal and a New Order-ish guitar line swirling through a kaleidoscope of sound, including Steve Reich-style handclaps. It was a cousin to all the PSB songs of the same time about driving. On Never Let Me Down Again (which charted low but became a signature tune), the big beat propelled the band well into the next decade.

A bigger hit, Strangelove, came with a taut rhythm that echoed Cameo’s Word Up. The reservoir of influence was seemingly bottomless, taking in Eastern music on Sacred. On pneumatic torch song I Want You Now, there was sampled porno panting and accordion exhaling (Smash Hits thought Depeche were blowing up a paddling pool).

It featured Gahan’s most daredevil phrasing yet, a testament to what a powerful singer he’d become. Then there was the Gore-sung Things You Said, Computer World sobbing inside a song as sad as early Eurythmics.

Music For The Masses

Streamlined and muscular, Music For The Masses oozed confidence. It blended outré stylings with the heft of rock, yet was made by machines once thought of as weedy, though guitars were more prominent; the band joked it was their ‘electronic metal’ album.

Lurking within these beefy, synthetic stadium-fillers were Gore’s most anti-macho lyrics; an ambivalence about the road to global mega-stardom the band were on?

They had become an unassailable musical force and done so on their own terms. The Music For The Masses cover art said it all; loudspeakers in the great outdoors (the Peak District), blaring from reservoirs and power stations, imagery as monolithic as U2‘s on The Joshua Tree.

Crowning Glory

Pink Floyd’s artwork, their imperial anonymity of the 1970s was an even better comparison, big music wrestling with big themes that didn’t need faces to sell it. Not that Depeche Mode were invisible. Collaborations with Corbijn continued for the videos.

They drifted through Paris on Strangelove, shot in grainy, stylish black and white with statuesque models for co-stars, a flash forward to Bruce Weber/PSB’s Being Boring, Madonna’s promos, even Herb Ritts’ Calvin Klein ads.

Depeche Mode’s 1980s culminated in one ecstatic moment on the Music For The Masses Tour at the Pasadena Rose Bowl in June 1988, supported by Wire, Thomas Dolby and, most significantly, formative influence OMD; the crowning achievement of a sell-out US tour.

Stadium Stars

One image in the DA Pennebaker film 101 sums up the evening and the heights Depeche Mode had ascended to. Gahan stands exultant, chest puffed out, arms swaying as the 65,000-strong crowd emulate his move in the California breeze. The man whose dancing Smash Hits once described as “gimpy” was now the Rock God of synth-pop, and his band were its one true stadium act.

After the gig, panic set in; “What now?” thought Gahan to himself, certain it would never be this perfect again. The best was arguably yet to come. But then again, so were the darkest days of all…

For more on Depeche Mode click here

Read more: Top 40 Depeche Mode songs

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.