Making Depeche Mode’s Music For The Masses

By Felix Rowe | November 7, 2022

We revisit the Mode’s game changer – an adventurous, hedonistic drive into unchartered territory that brought them both critical and commercial acclaim…

There’s only so long you can play the ‘outsiders’ card. Depeche Mode have built a career on it. Despite shifting 100 million records and filling stadiums the world over, they still to this day have never won a Grammy.

Yet having finally scrambled their way into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2020 (third time lucky), the pretence is over. Depeche Mode are now firmly embedded in the establishment.

Back in 1987, however, when they called their sixth album Music For The Masses, they were still very much the oddball underdogs.

Rather than a pompous display of arrogance, it was a barbed in-joke at their supposed commercial paucity (breaking news: Depeche Mode do gags).

But it turns out the joke was on them: Music For The Masses became the self-fulfilling prophecy that propelled them into the big league Stateside, filling cavernous venues and inducing levels of adulation that would baffle commentators on home soil.

Arguably the best was yet to come – see 1990’s Violator – but Music For The Masses was the point where critical acclaim and commercial success finally intersected.

Everyone knows the back story: initially dismissed as lightweight upstarts, Depeche quickly rebounded to the other extreme, exploring increasingly darker terrain, experimental industrial sounds and kinky imagery.

There was no shortage of cracking singles throughout. But, really, were they going to be booked to perform Master And Servant on Saturday Superstore?

Their wish to be taken seriously was granted with 1986’s Black Celebration, which garnered cult acclaim and set

the template for a new breed of doom-laden alternative rock (see Nine Inch Nails).

But on Music For The Masses, the darkness, experimentalism and pop sensibility coalesced into a winning formula that both brought the acclaim the band craved and put bums on seats.

Found sounds remained a fundamental part of the creative process. Crucially, though, they were kept in check within the greater whole.

Fresh impetus

Music For The Masses was the group’s first album without Mute Records mentor Daniel Miller playing a central role in its production: a mutual decision to hit the refresh button, with Miller increasingly busy on his label’s wider roster.

In the official making-of documentary, Martin Gore acknowledged the need for “some fresh impetus”, while Miller noted it was a “breath of fresh air” and “a huge weight off my shoulders” to relinquish day-to-day responsibilities.

Various producers were mooted, with the band gravitating towards Dave Bascombe, who had recently engineered Tears For Fears’ seminal Songs From The Big Chair.

There’s more than a passing resemblance between the moody atmospherics conjured on Tears For Fears’ Shout and Depeche Mode’s anthems for the dispossessed. Or, as Bascombe himself self-effacingly put it: “reverb”.

In the official making-of documentary, Dave Gahan explains: “Dave [Bascombe] just seemed like someone we could get on with”, while the sadly missed Andy Fletcher quipped: “Sometimes, you do need some new jokes, someone else to take the piss out of.”

In a revealing interview from 2020 with YouTuber Vaughn George, Bascombe shared in-depth insights into the recording process.

While credited as co-producer, Bascombe plays down his own considerable contribution to shaping the sound, suggesting he was principally employed to engineer, rather than to steer the creative direction.

By now, Depeche Mode were a well-established unit with a specific way of working.

In the Vaughn interview, Bascombe speaks of being amused by the “weird” unspoken rules in the set-up. It wasn’t his brief, he said, to challenge the status quo, and instead he assimilated himself into the workflow.

Much has been said about Depeche Mode’s division of labour. Once Gore had written and demoed a song, it was left largely to keyboardist Alan Wilder and the producer/engineer to flesh it out in the studio.

As George put it: “Martin was the architect and Alan the engineer.” Generally, Gore would only interject (through the intermediary Fletch) if he didn’t like something.

In Bascombe’s view, most of the band were bored by the nitty-gritty, meticulous nature of programming and the production process.

The natural musician and studio whizz, Alan Wilder, however, positively thrived in it. “Someone has to be steering the ship,” explained Bascombe, “and that was definitely Alan’s baby… Alan had the vision.”

Sessions began at Guillaume Tell, a converted Paris cinema, which proved fruitful owing to the range of orchestral instruments knocking about.

- Read more: Depeche Mode in the 80s

Depeche spent the first few days wondering about banging objects to make percussive sounds – an established ritual to build up a bank of samples for later use.

Work continued at Konk, The Kinks’ London studio, before finishing up the recording and mixing at Puk studios in Denmark (the building was sadly gutted by fire in 2020).

Like so many electro pioneers, Depeche Mode straddled that curious space between the obligatory ‘no guitars’ rule and a love of stomping glam rock. That influence starts to come to the fore on Music For The Masses.

Tellingly, the record kicks off with an isolated guitar riff, albeit heavily processed and triggered by a sampler. Come album six, Depeche were prepared to let their electro-purism slide, a recognition that one can only get so far with synths and samples alone.

Whether a sign of growing maturity, or just Gore’s boredom with synths, they no longer let a principle get in the way of progression.

Gore’s guitar work is never flashy – it’s the antithesis of the widdly theatrics that dominated hair metal at that point. His simple, repetitive riffs just sit on a groove, adding another textural element and human grit into the mix.

Behind The Wheel, for instance, is subtly enhanced by a few simple twangs from his Gretsch. These tentative steps laid the groundwork for a more dominant presence on later favourites – from Personal Jesus to I Feel You.

Different drum

Elsewhere, the Mode continued their quest to source only the finest sounds. Never Let Me Down Again’s earth-shattering snare was lifted from Led Zeppelin’s When The Levee Breaks.

“As a kid I’d always thought that’s the most fantastically exciting drum sound in the world!” Bascombe explained to Vaughn George.

Bonham’s gargantuan beat has since become one of the most sampled recordings in history, though Depeche’s producer was one of the very first to repurpose it (pipped, of course, by the Beastie Boys’ Rhymin & Stealin).

Martin’s voice was sampled, chopped up and reprogrammed to great effect on cuts including Behind The Wheel and grandiose closer, Pimpf.

A notable development of Music For The Masses is its epic, orchestral sound, enhancing the melodramatic, theatrical nature of the music – a combination of Bascombe’s engineering nous and Wilder’s classical influence and arranging qualities. The songs are typically structured around hypnotic cycles that build to a rousing climax.

Lyrically, Gore explores the open road, a recurring motif that evokes a sense of youthful escapism and adventure, while the driving metaphor plays into his fascination with sordid powerplay and who is in control.

Always a source of speculation, the ambiguity of Gore’s lyrics is heightened when filtered through Gahan’s unflinching baritone, delivered straight without a knowing wink.

To what extent is Gore condoning or condemning the acts of debauchery and depravity he describes? Is it perhaps another Gore in-joke: what are the filthiest words he can plant into his mate’s mouth?

As interviews attest, Depeche Mode have a cheeky side lurking beneath the veneer of doom. Bascombe had imagined they would be as intense as their output, though he found the opposite to be true, remembering the fun as much as the recording, and highlighting a certain kitsch-ness to the tracks they worked on.

Despite Andy Fletcher’s bookish appearance, it was he that apparently led the charge for nights out clubbing.

- Read more: Top 40 Depeche Mode songs

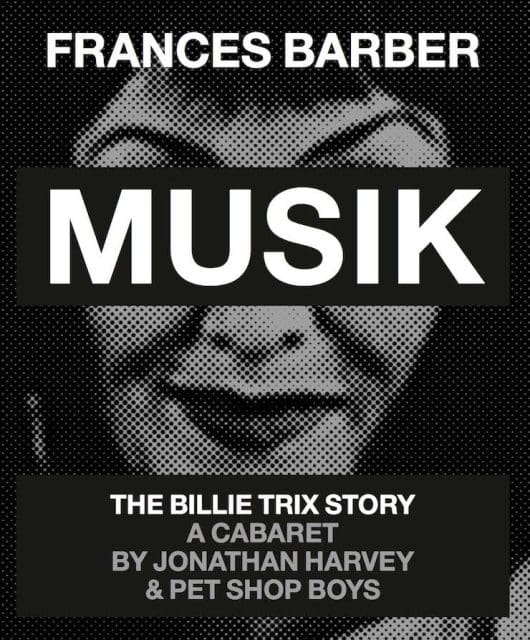

Gore had conceived the album title in advance of the sessions, providing a neat hook for the record’s visual aesthetic.

Cover art designer Martyn Atkins devised the idea of large-coned public address speakers broadcasting their message into open abandoned spaces. This is our grand statement, but is anyone listening? As it happens, quite a lot of people were.

The groundwork had been laid through US college radio support and Anton Corbijn’s stark but humanising monochrome videos enjoyed regular rotation on MTV.

They ended up playing for the masses, culminating in a huge show to 60,000 fans at the Pasadena Rosebowl, supported by fellow Brit pathfinders OMD, Thomas Dolby and Wire.

The madness of the era is captured in D.A. Pennebaker’s Depeche Mode: 101 concert film; a pivotal moment, recently re-released for the first time on Blu-Ray in a deluxe package.

Before the crash

The frenzied reaction Stateside could only be described as akin to Beatlemania. OMD’s Andy McCluskey has looked backed hilariously at that three-month tour, including the gentle rivalry between the bands which extended to spirited cricket matches featuring the crew on days off.

Europe was equally enraptured. Bascombe compares the fervour of Pimpf blaring out of the announcement speakers opening a show in Paris as being like attending a political rally.

Depeche Mode had reached a new summit – though in hindsight, it set them up for the greater fall.

In the ensuing years, things would unravel with various mental health struggles, communication tested to its limits, Wilder’s 1995 departure and Gahan’s infamous brush with death a year later.

But putting aside the numerous challenges that lay ahead, Music For The Masses is a showcase of the definitive Mode line-up, on top form and playing to their strengths – not least, Wilder’s significant contribution to arranging and production.

Though regularly praised by fans, Wilder is very much the unsung hero of Depeche in wider perception, and Music For The Masses provides all the proof anyone would need of his skills.

Flanked by two classic Mode studio albums: Black Celebration from 1986 and Violator four years later, it deserves a place beside them as one of the band’s finest, most consistent and fully-realised collections.

Depeche Mode: Music For The Masses – the songs

Never Let Me Down Again

A bold statement of intent to kick off proceedings, the album opener (and second single) has all the hallmarks of a Depeche 2.0 classic: a driving beat, pulsing synths, chunky guitar, and, of course, the oblique Martin Gore lyric. A druggy hedonistic trip into oblivion, a homoerotic experience, or a bit of both… does it matter?

So far so good, but it’s that fantastic rousing orchestral climax that raises the track to a whole other level of greatness. Inspired symphonic samples, lifted from Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, demonstrate a growing musicality, sending Never Let Me Down Again into orbit.

The Things You Said

How to follow the ultimate banger? With the perfect comedown, of course. Gore delivers a slower, more atmospheric and understated post-apocalyptic ballad. Sparsely arranged, The Things You Said is built around a repetitive mournful vocal refrain, that recalls just a little bit of Morrissey in Gore’s legato delivery.

Critics might argue it never quite gets going, though it’s an exercise in restraint. Sometimes, the notes you don’t play are more important than those you do.

Strangelove

The lead single has become a fan favourite and live staple – a lively four-to-the-floor synth romp destined for dancefloors. The single came out five months before the album, while sessions were ongoing. As a result, the version that appears on the LP is a decidedly different beast.

Born out of a remix from Daniel Miller to simplify the arrangements and reduce a perceived sense of clutter, it’s notably more stripped back and, by default, takes on a slightly darker edge.

While both versions have their merits, many would say that this later interpretation, within the context of the wider body of work it’s a part of, is the definitive incarnation.

Sacred

Opening with atmospheric sounds and sampled choir snippets, lyrically it’s classic Gore thanks to the subversive religious imagery: “a firm believer and a warm receiver”.

Dave Bascombe wasn’t entirely happy with the track, suggesting later that his original cassette rough mix was much better, and it wasn’t as gritty and glam as it should have been. You can see where he’s coming from – it could be more sleazy and less ‘boppy’, but don’t let that detract from the great tune it is.

Little 15

A curious choice of single. The jaunty, sampled and programmed orchestral arrangement evokes Eleanor Rigby for the synth-pop generation. It’s a prime example of Alan Wilder’s skill at taking the bare bones of a Gore composition and sprinkling his magic over the top.

Bascombe has said that Little 15 was classic Alan in his use of orchestra samples. Wilder himself has noted that Little 15 initially proved challenging to structure and arrange, before finally slotting into place after taking inspiration from minimalist classical composer, Michael Nyman.

Gore’s ambiguous lyrics seem rather questionable, though the band have clarified it describes a conversation between a mother and her 15-year-old son about the challenges of growing up, going out and facing the world. Note the recurring road metaphors representing the idea of escapism.

Behind The Wheel

The third single taken from the album, Behind The Wheel features an interesting combination of uptempo club banger tempered by an almost sinister, unresolving chord sequence.

Wilder explained the nature of this revolving pattern in the official making-of documentary: “It’s this sequence of four repeating chords that never changes. It sort of reminds me of one of those optical illusion stairways, where you’re walking up the stairway and you never get to the top. Once you get round, you’re back at the bottom again… you can’t stop it, and that’s the beauty because of the driving analogy of the song.”

Compared to the single edit that cuts to the chase, the album version is much more drawn out, eking out the tension and atmosphere in a gradual climax, before eventually delivering on the promise, by dropping into those satisfying snare hits.

I Want You Now

Gore takes the lead vocal on this none-too-subtle smut-fest, that uses grunts and groans sampled from an adult film to create a groove. The creepy, heavy-breathing sound in the intro was created by pushing in and drawing out the air of an accordion, without playing the notes.

This recording was then sampled into a then state-of-the-art Fairlight CMI 3, which happened to be available at the studio. Though a cutting edge use of sampling at the time – and no doubt responsible for raising more than just the eyebrows of its listeners – it now feels more akin to a cheap gimmick rather than risqué innovation.

There’s an argument here that this is what the skip button was invented for.

To Have And To Hold

Beginning with Russian radio samples that bleed in from the preceding track, a moody, foreboding synthesizer drone follows, before the minimal beat kicks in: a thud kick and a colossal crashing snare.

A simple, repetitive vocal refrain from Dave Gahan carries one of Gore’s more filthy and depraved lyrics (“I feel diseased, down on my knees” he intones like a dispassionate preacher delivering the Sunday sermon).

From promising beginnings, To Have And To Hold feels a little unfinished – having gone to all that trouble creating the brooding atmosphere, it rather peters out, building up to the big rousing chorus that never arrives.

Nothing

An infectious nagging riff leads into a powerful electro number – one of the more underrated hooks from the Mode’s catalogue. If nobody else has sampled this then they’re all missing a trick. Depeche Mode had a rule about not using hi-hats, although what could initially be seen as an offending example on Nothing is in fact taken from a sample of a pneumatic coach door.

Several years earlier, when working with another group, Bascombe noted the strange swishing sound of their tour bus door opening and closing. Luckily, he had the canny foresight to record it for posterity, on the off chance that one day it would fit rather nicely on an electro-pop masterpiece he happened to be co-producing.

Gore’s guitar gets another airing with a subtle chorus part. The falsetto ‘ooh oohs’ are pure bubblegum pop, and proof that Depeche Mode retained an ear for a hook and an eye on the charts.

Pimpf

The overblown operatic pomp of Pimpf is almost something Muse would turn down for being just too ridiculous. The Wagnerian instrumental takes its name from a Nazi magazine for boys in the Hitler Youth, which gives some indication of its general vibe.

It’s a curio in the catalogue, originally released as a B-side to Strangelove. Apparently, it would have remained at that, had Bascombe not had another crack at mixing it while the group were occupied shooting a video. It became their walk-out music for the ensuing tour, and succeeded in whipping the crowd into a frenzy.

Wilder has spoken about many tracks on the record that build from humble beginnings into a big crescendo, and Pimpf is the archetype. He’d been listening to minimalist composers like Philip Glass at the time, though you wouldn’t describe Pimpf’s bombastic climax as minimalist in any sense.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!