Dr Robert interview: A kind of magic

By Paul Kirkley | July 4, 2023

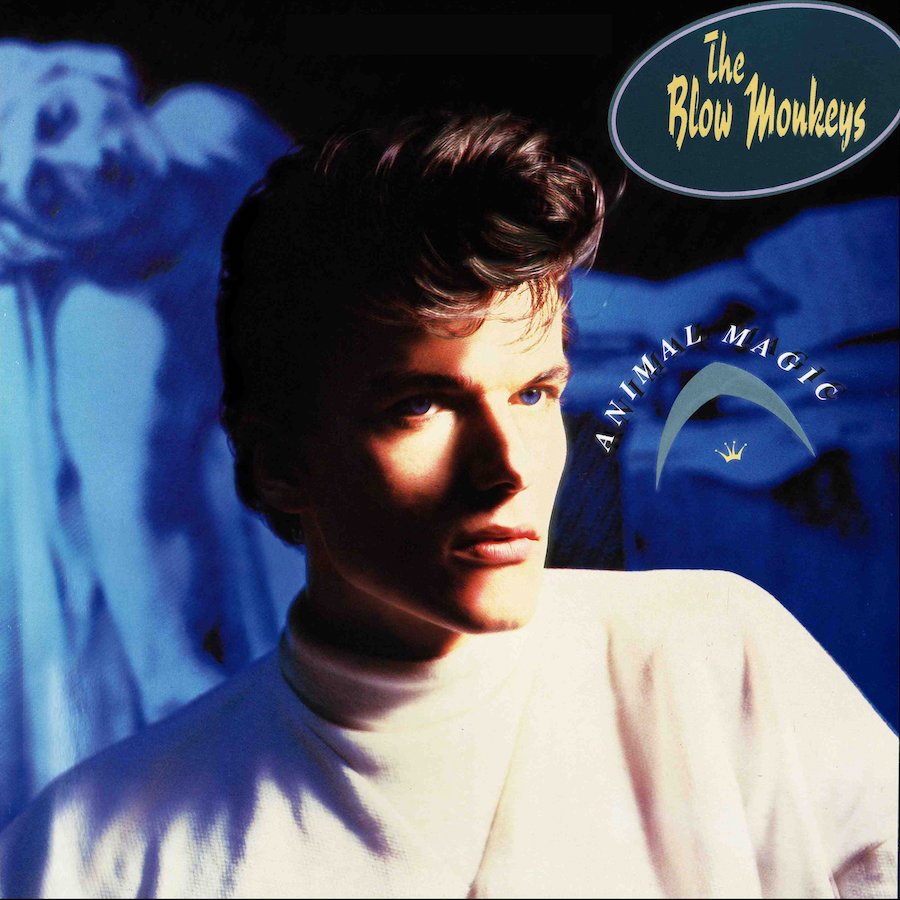

As the Blow Monkeys’ Animal Magic returns as a new deluxe reissue, frontman ‘Dr Robert’ Howard tells Classic Pop how his plan to rope in a certain children’s TV legend came perilously close to ruining the whole thing…

As the Blow Monkeys’ Animal Magic returns as a new deluxe reissue, frontman ‘Dr Robert’ Howard tells Classic Pop how his plan to rope in a certain children’s TV legend came perilously close to ruining the whole thing…

“I hate that phrase – sophistipop,” says chief Blow Monkey Robert Howard, rolling his eyes. “I’ve tried to remove it from Wikipedia, but they won’t let you. I don’t know what it means. But whatever it is, I don’t want to fucking be it.”

Well this is awkward. Not just because the S word is a beloved staple of the Classic Pop style guide, but because the record we’re here to discuss – the Blow Monkeys’ 1986 sophomore album Animal Magic – is widely considered to be a high-water mark of the form.

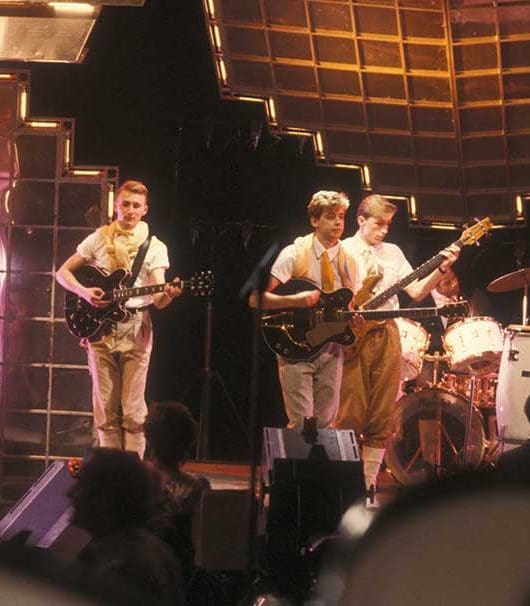

The first Blow Monkeys’ record to make a commercial splash, Animal Magic arrived in the slipstream of breakthrough single Digging Your Scene, which was a Top 20 hit on both sides of the Atlantic.

Blending slick, soulful (and, yes, sophisticated) pop with deceptively biting lyrical dispatches from the frontline of Thatcher’s Britain, it might not have been the band’s most successful album – in the UK, at least, that honour falls to its follow-up, She Was Only A Grocer’s Daughter – but nearly four decades on, there’s a strong argument for it being the Blow Monkeys’ definitive 80s statement hence its recent reissue – the second in a decade – is a deluxe, 4CD bells-and-whistles edition.

For the man they call Dr Robert, the Blow Monkeys’ singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, the album’s Motown-meets-New Wave aesthetic has its somewhat unlikely origins on the terraces of King’s Lynn Town FC.

“King’s Lynn is a soul town,” says Robert, who’d moved to Norfolk from his native Scotland as a child. “And I’d stand on the terraces with my dad, in the freezing cold, listening to the half-time music of Freda Payne singing Band Of Gold – and being transported.

“Plus I had two sisters who were 10 years older than me, who’d bought everything that came out in the 60s – Motown, Bacharach and David, The Beatles, obviously. All those records had a big impact on me.”

His further musical education, though, came with a tragic backstory: when Robert was 15, his father died, and he and his mother emigrated to join his sister in Australia.

“Going from King’s Lynn to Sydney was like going from black and white to colour,” he recalls. “This was March 1977, so punk had just broken. The first band I ever saw in Australia was The Saints, followed by the Boys Next Door, which was Nick Cave’s first band.

- Read more: Robert Palmer – Simple Irrefutable

“My sister had a guitar lying about and a book, The Eagles Made Easy. By the time she came back from work, I’d learned the whole book – even though I didn’t know any of the songs. For me, playing guitar was like meditation. I had to do it every day.”

Looking back, was throwing himself into music partly a coping mechanism, to help him deal with his grief?

“Absolutely,” nods Robert, who’s talking to CP over Zoom from his long-time home in southern Spain. “My father died around the same time as Marc Bolan – two very big things in my life.

“I took a couple of years off school and just sort of hothoused myself, playing along to early Tyrannosaurus Rex records, then The Clash, and early Jam. I just played endlessly. In retrospect, it probably was a form of therapy. And it still is.”

By 1985, Robert was back in the UK and hatching plans with bandmates Neville Henry (sax), Mick Anker (bass) and Tony Kiley (drums) for what would become the Blow Monkeys’ second album.

By 1985, Robert was back in the UK and hatching plans with bandmates Neville Henry (sax), Mick Anker (bass) and Tony Kiley (drums) for what would become the Blow Monkeys’ second album.

Keen to evolve their sound from the jazz-inflected post-punk of their recent debut, Limping For A Generation, Robert instinctively found himself reaching back to those frozen Norfolk footie terraces.

“I can look back at it now and theorise how we got there – how I was tapping into that kind of latent soul bug,” he says. “But at the time I was just writing the songs that were coming into my head.”

- Read more: Top 20 80s collaborations

As well as Freda Payne and Marc Bolan, “there were still remnants of things I’d been into when I was in Australia – bands like The Laughing Clowns, that had that brass thing going on,” he says, of the Sydney post-punk combo’s fusion of punk guitar, be-bop drums and horn section.

“The producer, Pete Wilson, had a lot to do with how [Animal Magic] came together. I remember playing him things like Forever Changes by Love and saying how I loved that mix of brass and strings, but underneath it there’s a garage band playing along.

“That’s what I wanted. I think the album ended up being a bit smoother than that. But in general it sounds good, it sounds like a band. There’s a coherence to it,” he says, citing the swooning soul of Aeroplane City Lovesong and Bolanesque title track among his highlights.

If things had gone to plan at the time, though, it’s possible Animal Magic might not be quite so highly regarded today.

Encouraged by Wilson, who had produced Sham 69’s ‘punk rock opera’, That’s Life, Robert was keen to write a concept album, complete with spoken word sections between the songs.

“Do you remember Johnny Morris – the zoo guy who had a programme called Animal Magic?” he says of the one-time kids’ TV staple. “I tried to get him to do it. He said, ‘Thank you very much, but no thanks’. And thank God for that. I dodged a bullet there!”

Released in February 1986, Digging Your Scene was “kind of a life-changer,” remembers Robert. “It’s the record for which we’re probably best known around the world.”

And while Spotify begs to differ – 1987’s It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way (the Blow Monkeys’ only UK Top 10 hit) has so far racked up a couple of million more streams – it’s certainly true that Digging Your Scene is the song that turned Robert into a pop star.

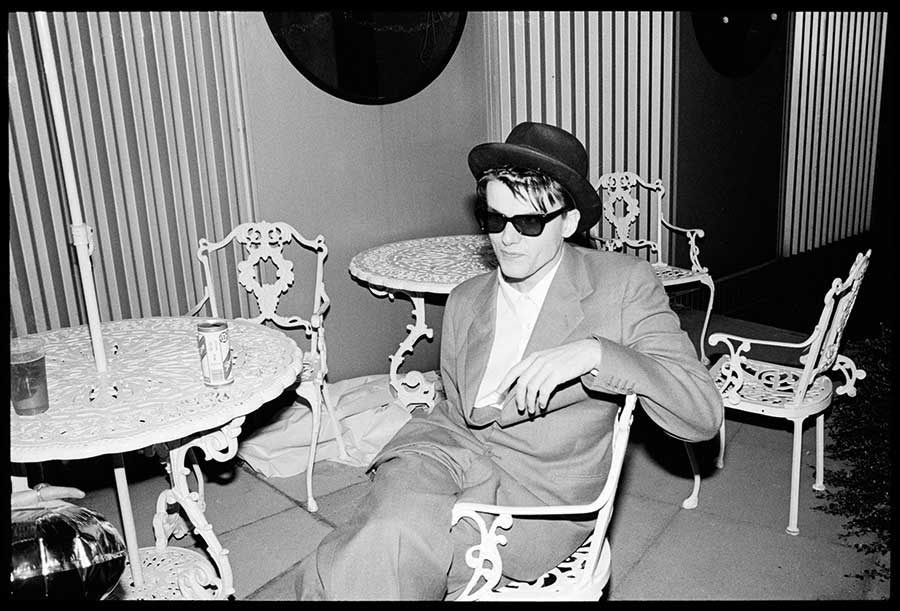

Though not, as it turned out, an entirely comfortable one: for Robert, there was always an uneasy tension between the socialist soul boy punk and the pretty boy pop pin-up.

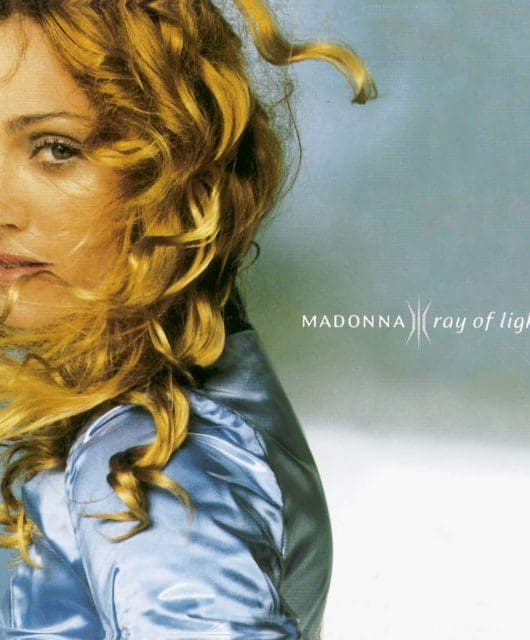

“I was just too good looking for my own good,” he laughs. “And I went with it. Even on that fucking stupid [Animal Magic] sleeve, where I look like one of the geezers from a-ha.

“It was a schizophrenic shift [from the previous album], which might have been to our detriment a bit. But I’m not complaining.

After Digging Your Scene, we went from playing clubs to flying into the States to support Robert Palmer at Red Rocks in the Arizona desert, and doing American Bandstand with Dick Clark. It was a trip, you know.”

- Read more: Heaven 17 albums: the complete guide

There were moments, says Robert – like having green foam sprayed at you by someone dressed in a monster suit on Saturday morning TV – when it all seemed a bit surreal. But it was also great fun. “I was a single man at the time,” he notes, with a twinkle.

“The only thing that bothered me was that, as a band, we had a really strong bond. But there were murmurings in the record company that maybe there was a bit of a George Michael vibe here… ‘Maybe we could get you into that stratospheric pop star territory?’ That was never going to happen. Mostly because I was just shit at all that,” he laughs.

Besides, as pretty as both he and the tunes may have been, Robert was also a political protest singer: Animal Magic, lest we forget, literally features a song called Burn The Rich, inspired by a slogan sprayed across the bank opposite the singer’s Brixton flat – a location that gave him “a bird’s eye view” of a febrile period of British history.

“It was the 80s – everything was political,” he says. “And, much as I love Billy Bragg, we can’t all be Billy Bragg. I thought it was okay to still have that kind of androgynous, flamboyant nature. That didn’t cancel out the fact that, deep down, I was a socialist who thought what Thatcher was doing was against nature.”

Follow-up album She Was Only A Grocer’s Daughter’s title (plus the lyrical message of It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way) offered further proof of the then-Prime Minister’s rent-free existence in Robert’s head.

But despite those twin successes – plus an extra-curricular UK Top 10 hit for Robert, duetting with Chicago house singer Kym Mazelle on 1989’s Wait – by the start of the 90s, it was clear the Blow Monkeys’ imperial phase was over.

“I knew it was going to happen, because the cars had stopped coming,” he says of the band’s subsequent (amicable) split. “I was just exhausted. It had been 10 years with my foot on the pedal, never stopping. I had a young family, and it felt like the right time.”

- Read more: Top 15 Sophisti-Pop Albums

Even so, Robert admits, that there was “a sense of rejection. Looking back, there were a couple of years where I felt a bit wobbly, and I drank too much. Because it happened very quickly. People stopped calling, and you think, ‘Well, is that it now?’

“That’s what really sorts the men from the boys. Because that’s when you have to ask yourself, ‘what is it that I really want to do?’ And what I wanted to do was play music, whether there was an audience there or not.”

An in-car cassette copy of Bob Dylan’s Desire kickstarted a run of Greenwich Village-inspired solo studio albums, before the Blow Monkeys reformed in 2007 for a second act that has proved more enduring (and produced more albums) than the first phase.

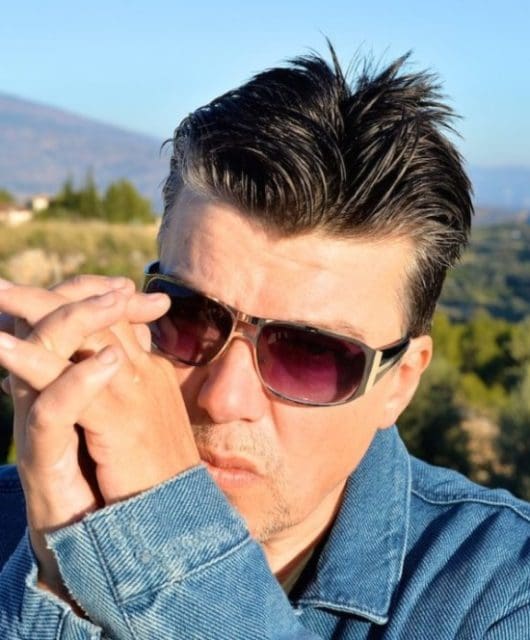

Now 61, Robert – who has a grown-up son and daughter with his wife Michele – combines Blow Monkeys duties with projects such as Monks Road Social, a loose collaboration of artists whose rolling roster has included everyone from Paul Weller to former Time Lord Peter Capaldi (Robert produced the latter’s recent debut album, St. Christopher).

Now 61, Robert – who has a grown-up son and daughter with his wife Michele – combines Blow Monkeys duties with projects such as Monks Road Social, a loose collaboration of artists whose rolling roster has included everyone from Paul Weller to former Time Lord Peter Capaldi (Robert produced the latter’s recent debut album, St. Christopher).

He also still picks up his guitar and plays every day. “I’ve often thought I’ll probably end up busking again one day,” he smiles. “And I’d be happy to do that.”

In the meantime, he’s quietly pleased to see Animal Magic getting the deluxe treatment – its original 12 tracks have been expanded to a whopping 47 via B-sides, demos and remixes – and, as a collector, is particularly excited about the single-disc white vinyl version.

So is this the definitive, final word on Animal Magic? “I hope so,” says Robert. “I suppose when I die, they might find some other demos somewhere, but I think this is it.

“I’m happy to help BMG make the most of it, because they told me it was part of their ‘iconic series’. If you live long enough, you become iconic. At some point, I went from being ironic to iconic,” he chuckles. “So I’m happy with that.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!