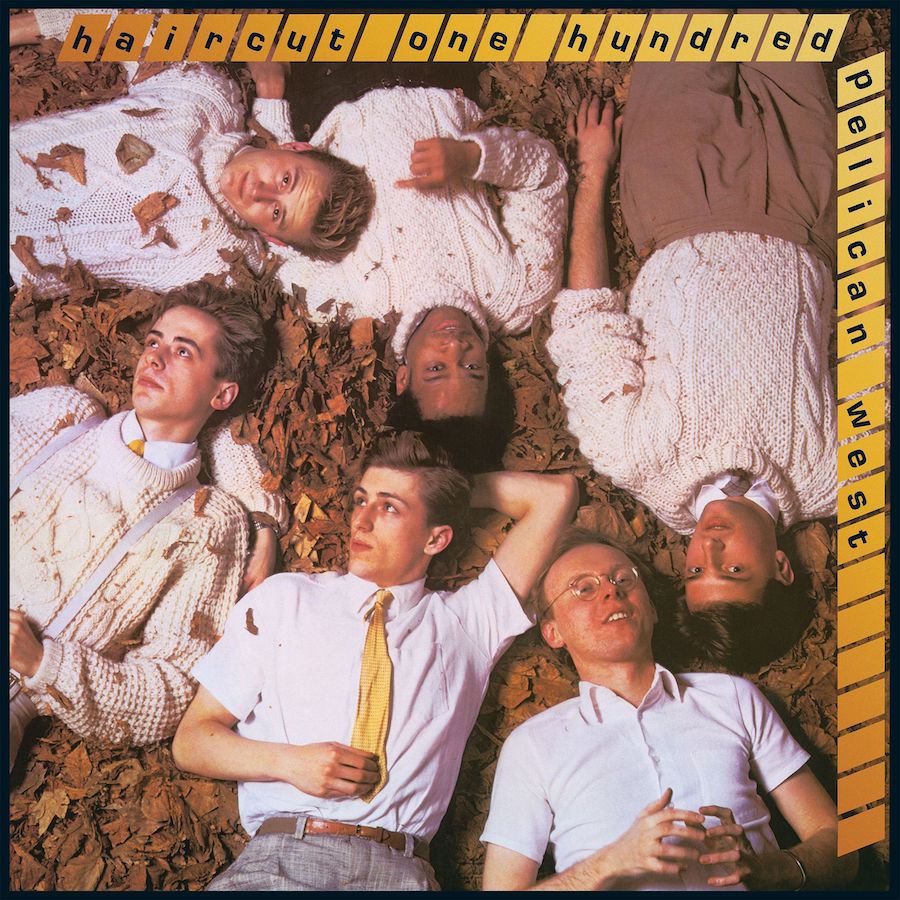

Haircut 100 interview: “We always had the confidence that we were something special”

By John Earls | July 1, 2023

Shiny enough to have their own comic strip and potential TV sitcom, Haircut 100 were also an odd mix of six diverse personalities, incorporating post-punk, jazz, Brazilian rhythms and martial arts movie soundtracks into one pop masterclass. Even 40 years after the original lineup’s only album together, there’s still nothing quite like Pelican West. As the band reunite for a one-off show to celebrate a new boxset, they reveal: “There was an energy in Haircut 100 that we all managed to harness. We were like a comet.”

Shiny enough to have their own comic strip and potential TV sitcom, Haircut 100 were also an odd mix of six diverse personalities, incorporating post-punk, jazz, Brazilian rhythms and martial arts movie soundtracks into one pop masterclass. Even 40 years after the original lineup’s only album together, there’s still nothing quite like Pelican West. As the band reunite for a one-off show to celebrate a new boxset, they reveal: “There was an energy in Haircut 100 that we all managed to harness. We were like a comet.”

Shiny enough to have their own comic strip and potential TV sitcom, Haircut 100 were also an odd mix of six diverse personalities, incorporating post-punk, jazz, Brazilian rhythms and martial arts movie soundtracks into one pop masterclass.

Even 40 years after the original lineup’s only album together, there’s still nothing quite like Pelican West. As the band reunite for a one-off show to celebrate a new boxset, they reveal: “There was an energy in Haircut 100 that we all managed to harness. We were like a comet.”

The more that anyone looks at Haircut 100, the less sense they seem to make. The band made brilliant pop music with Love Plus One, Favourite Shirts (Boy Meets Girl) and Fantastic Day, delirious singles that hold up against any other smashes of 1982’s perfect chart year.

Parent album Pelican West was only kept from No.1 by Barbra Streisand’s Love Songs and Haircut 100 had their own devoted fan army, The Scissors. Alongside Adam Ant, they were the sole pop turn colourful enough to receive their own comic strip in kid’s TV magazine, Look-in. Like Madness, they even had a sitcom pilot drawn up.

And yet… just look at them. There are six people in Haircut 100 for a start, a band musically rich enough to require a saxophonist and a percussionist alongside the usual guitar/bass/drums formula.

The more you listen to Lemon Firebrigade and the dizzying Kingsize (You’re My Little Steam Whistle), the more layers there are to unpack. Everyone knows “Where does it go from here?/ Is it down to the lake I fear?”, yet Love Plus One’s chorus is just one of Nick Heyward’s mighty lyrics, simultaneously immediate and inexplicable.

They were a cult sensation in North America, predating Ralph Lauren’s reinterpretation of the English gentleman look for a Stateside audience.

This was a band as likely to wear cricket jumpers or sou’westers, while also musically inventing Blur’s mix of nostalgia and modernism a decade early.

Haircut 100 were as unfathomable as they were magnificent. And, five decades on, Pelican West still sounds bloody magnificent.

“We were a blank canvas for everyone to do their stuff on,” theorises Nick. “I’d come up with songs to inspire everyone else to get colouring them in. Everyone played their role.”

Jazz-loving bassist Les Nemes admits: “It’s only recently that I realised we had our own sound. But we never questioned that we were going to succeed. We never said: ‘If we make it,’ it was always: ‘When we make it.’ We always had the confidence that we were something special.”

Guitarist Graham Jones, an experienced punk who eventually fulfilled his love of Bruce Lee soundtracks by becoming a fourth dan karate black belt, reasons: “I’m not a great fan of all the songs on Pelican West. I’d like some of it to be harder-edged. But, in a band, there’s always give and take. What you hear is everyone playing to the best of their ability. It’s an album with no filler.”

According to Marc Fox, the percussionist who was into Krautrock and Brazilian music, last to join Haircut 100 on the recommendation of saxophonist Phil Smith: “Pelican West didn’t sound like anything at the time, because it’s peculiar – both in how it was recorded and the nature of the people who made it.”

Growing up in David Bowie’s south London hometown of Beckenham, Nick and Les were first to meet. Mutual friend Tim Jenkins told Nemes that Heyward’s band needed a bassist.

Nick’s parents ran posh bar The Ski Club Of Great Britain, part of the central London estate where Upstairs Downstairs was filmed, and later immortalised in Fantastic Day’s B-side, Ski Club.

“I chucked my bass gear into my 1967 VW Beetle and drove off to audition for Nick,” recalls Les. “The first song Nick played me, Spanish, was like nothing I’d ever heard. It had a Talking Heads approach, with one-note solos. I was completely smitten.”

Graham, who had already played a punk festival with Sham 69 singer Jimmy Pursey, was next on board. “Mine and Nick’s girlfriends were mates who were punks,” laughs Jones.

“When they’d go out drinking in Beckenham, we got chatting as the girlfriends’ boyfriends. At the time, Nick’s band was more post-punk and based on XTC, while I was into Generation X, still thrashing out my guitar sounds with heavy distortion.”

Then called Moving England, future Sex Gang Children drummer Rob Stroud completed the line-up. “Moving England were really good,” insists Graham.

Then called Moving England, future Sex Gang Children drummer Rob Stroud completed the line-up. “Moving England were really good,” insists Graham.

“I was always amazed by Nick’s ability, and Les’ basslines were very unusual, too. Les’ playing always wandered up and down the whole neck of the bass. You can hear in Lemon Firebrigade and Love Plus One how Les gives a great movement to the music.”

Rob was quickly replaced by Pat Hunt. Gutted at having narrowly missed out on being part of Tubeway Army, Hunt was determined pop stardom wouldn’t elude him second time round. The band moved into a flat together above a florist in west London’s Gloucester Road.

“One piece of advice I’d give to bands has stayed the same,” offers Heyward. “If you want to be a band, you’ve got to act like a band and have something to say. I once saw Sparks walking down Beckenham High Street. They had the whole ethos of living and breathing being in a band.

“I thought bands walked down the street together all the time when they weren’t on stage. It’s important. At 19, we were way too cool to think that we were copying The Monkees by living together.

“We tried to live out the dreams of the bands we’d seen on TV and in the pictures I’d stared at for hours in magazines. We had that vision both from the start of Haircut 100, and once we got successful. I still play a Mustang bass because it’s what Tina Weymouth looked so cool playing in Talking Heads.”

That band mentality meant a change of name from Moving England arrived easily. At a band meeting, someone suggested “Haircut”, someone else offered “Hundred”, then Nick thought of fusing the two names.

Marc explains: “There was no Svengali figure telling bands what to do in 1981. When we first did Top Of The Pops, we saw Depeche Mode in their rubber trousers, Tony Hadley with a rug on his shoulders and Boy George in the corner, looking completely unique. We were different from everyone else, but so were all the other bands.

“There was no choice of options, so you ended up making what worked for you from your group of individuals. Even our name: ‘Haircut’ and ‘100’? We laughed our way into the chart. Provided you didn’t fall into fits of laughter saying ‘Haircut 100’ to other people, after three times of saying it, it became reality.”

- Read more: Nick Heyward Albums: The Complete Guide

Rather than appear everywhere on gig listings, the re-christened Haircut 100 were selective in their shows. “We wanted to create an event each time we played,” remembers Graham.

“We’d give out wine and marshmallows to the audience, because who hands out marshmallows at a gig? We didn’t feel we needed to play everywhere under the sun just for the hell of it.”

By then, their line-up had been bolstered by recommendations from Joe Dworniak and Duncan Bridgeman, part of Britfunk band iLevel and bosses of Haircut 100’s rehearsal studios in Leyton, east London.

They suggested saxophonist Phil Smith, as Graham recalls: “We needed a saxophonist for one song at a show at The Embassy Club on Bond Street. Phil stood on the balcony.

“When he started playing, everyone turned around, going: ‘What’s that?’ We always tried to introduce elements to make the gigs more interesting, and there was obviously a lot more Phil could bring.”

“Everything in Haircut happened so quickly,” continues Marc. “I wasn’t aware of any huge interest in the Haircuts, it was just my mate Phil saying: ‘I think you’ll like this lot.’ From first turning up with a bag of percussion to being in the studio making Pelican West was a matter of months.”

It helped that their singer knew how Haircut 100 should look as well as sound, bolstered by his day-job in a design agency. “I thought like I was the art director of the band,” reflects Nick.

“I always carried a portfolio with me, which had pictures of us and our potential artwork. I knew not to leave the visual ideas up to other people because, if you don’t take control of your life, you can’t complain when others do it instead.”

“The looks for the band always came from Nick,” says Les. “We lived near Kensington Market and got a lot of our gear from there, mixing and matching from ideas Nick suggested. Nick would have a diamond jumper straight out of Chariots Of Fire and I’d think ‘OK, fine with me.’”

Heyward insists the imagery wasn’t always thought out, stating: “It’s funny, the things that stuck around. I put on

a sou’wester once just because I didn’t think anyone had worn one in pop before. I went to a fishing shop off Piccadilly Circus, where I got the big hat and socks. Then I thought: ‘I could go the whole way here, go full fisherman and get waders, too.’ Jonathan Ross once told me: ‘I went out dressed like you once and nearly got beaten up.’”

Spandau Ballet were a key influence, as Nick remembers Chant No.1 “blowing London apart”. They even had a meeting with Spandau’s charismatic manager, Steve Dagger, hoping he’d represent Haircut 100, too.

“Steve has a constant smile about him and, when we met him, he had a snake around his arm,” laughs Nick. “I thought: ‘OK, that’s unique’. The meeting didn’t work out, but that’s how strong Spandau’s influence was.

“They were gods to us. When Marc joined, he was a tall, hairy-chested man who could have been in Spandau. The rest of us were all under 6ft and couldn’t even grow facial hair.”

- Read more: The story of 1983 in music

Haircut 100 quickly signed to Arista Records, who hooked them up with The Beat’s producer, Bob Sargeant. “The Beat and The Specials were so far advanced of us, we thought there was no way we could sound that good,” raves Heyward.

“Then we got together with Bob, and it was, ‘Wow, he’s making us sound like Mirror In The Bathroom!’ Everyone in the band had their own influences. Bob was the one able to bring it all together.”

Favourite Shirts became the first single. At that point, it became clear Pat Hunt had to leave. Graham reasons: “Pat couldn’t keep pace. It didn’t matter if mistakes were made live but, in the studio, you’re on a schedule and it wasn’t happening.”

Respected soul drummer Blair Cunningham joined from Shake Shake, the other band of rehearsal studio managers Joe and Duncan.

Respected soul drummer Blair Cunningham joined from Shake Shake, the other band of rehearsal studio managers Joe and Duncan.

“They were very understanding,” attests Les. “They said: ‘Look, it happens.’ If you’ve got Blair behind you, you can’t go wrong. With a drummer like Blair driving the music along, it’s going to sound fantastic. I’ve never heard him say a bad word about anyone. He just wants to get on with the job.”

Another fallout from Favourite Shirts came when Marc was forced to quit his day job as a teacher at Lewisham Girls School in south London. He laughs: “As soon as I was on Top Of The Pops, I was called in to see the headmistress and told: ‘We have reason to believe you’ve contravened Inner London Education Authority rules by contracting yourself to the BBC. We think you should choose between us and a pop career.’”

At only 21 years old, Marc was distant from his older teaching colleagues, additionally feeling at sea acting as more of a carer than an educator for many of his disadvantaged pupils.

- Read more: Pop on the Tyne: Remembering Razzmatazz

With all six of the band able to fully concentrate on recording, their debut album took shape under Bob Sargeant’s tutelage.

“I don’t think there’s been much since that’s been derivative of Haircut 100,” ponders Nick. “There have been no bands copying Haircut 100 at all, really. Lyrically. I drew from pioneers like David Bowie and Marc Bolan, going past my brother’s bedroom, hearing Ride A White Swan and thinking: ‘Why are you riding a white swan?’ I liked art-pop, singing words that didn’t make sense. What I wrote was different and mixed up. This wasn’t The Carpenters.”

In part, Pelican West sounded so unique as it was one of the very first albums to be recorded wholly digitally. “Bob had tried digitally recording with The Beat,” says Marc.

“We were blown away by the clarity, by how you could isolate and individuate every sound. We were a bright and shiny looking band, and our sound reflected that.”

Recording techniques have largely reverted to the more natural analogue way of making music, as Marc explains: “We were making music at an unusual point in time. Our songs still jump out on the radio but, while it still sounds modern, it does so in a way we look on 40 years later as being a little naïve.

“Also, after Pelican West, automated dance music suddenly happened. There was no such thing in 1982, so we were at the mercy of trying to make ourselves into machines.”

Pelican West’s glossiness made instant heartthrobs of the band, much to their bemusement. Nemes notes wryly: “Generally, the fandom was great fun. It was only when girls would press the buzzer from 7am at the apartment in Gloucester Road when we were home that it was a bit much.

“We had to call the fire brigade a couple of times when fans got stuck in the railings outside.”

The band never got to see the pilot sitcom script penned by Not The Nine O’Clock News writer Chris Langham, with a new tour quickly interrupting any putative filming schedule.

Graham remembers: “Having our own comic strip in Look-in and talk of a sitcom was hilarious. Daft as it was, having your own comic strip is a huge privilege, because how many bands get that?”

Heyward agrees, pointing out: “I’d seen footage of The Beatles hysteria and thought: ‘That looks really good!’ But that stuff had to go, because it got in the way of the music.

“It’s only now, when you see the pictures of screaming fans, that you see how sweet it all was and think ‘Bless your hearts.’ The screaming would have stopped, as it did to Depeche Mode and Blur.”

Hysteria was never an issue in the States, where Haircut 100 generally attracted a more considered response, though Nick remembers: “On our first walk as a band away from our fancy hotel on Gramercy Park, we nearly got beaten up. We got so much stick, because 1982 New York was not ready for the way Haircut 100 looked. They wanted The Doobie Brothers.”

Hysteria was never an issue in the States, where Haircut 100 generally attracted a more considered response, though Nick remembers: “On our first walk as a band away from our fancy hotel on Gramercy Park, we nearly got beaten up. We got so much stick, because 1982 New York was not ready for the way Haircut 100 looked. They wanted The Doobie Brothers.”

At least, as Graham describes, the US tour shows were a blast: “The Americans actually listened to what we were playing. They appreciated our musicianship, which made us play differently. We started to mature as musicians there.”

- Read more: The story of 1981 in music

A homecoming tour climaxed with two shows at Hammersmith Odeon, released as part of the new boxset of Pelican West. “We were unstoppable live,” beams Nick. Les adds: “We were living out our dream. The stage was where we felt most comfortable, because it’s where we got to hang out as mates, doing what we loved most.”

One-off Beatles-y single Nobody’s Fool continued Haircut 100’s reign, going Top 10 six months after Pelican West. Sadly, it was the original lineup’s last hurrah.

Although Pelican West had only been released in February 1982, Arista demanded a second album be ready to release by Christmas the same year.

Somehow, enough songs were assembled for recording at Oxfordshire residential studio The Manor, where Nick’s heroes XTC had recorded English Settlement just weeks before.

But the workload caught up with Heyward, who stopped attending the follow-up sessions at London’s industrial studio, The Roundhouse. Unbeknownst to his bandmates, Nick convalesced at a nursing home.

“Mental health is communicated so differently now,” the singer says. “Bands wouldn’t think twice about cancelling a tour. There had to be pioneers for that. Bands like us paved the way in showing how not to split up.”

Graham adds: “At the time, I don’t think there was anything we could do. We were in the middle of a successful pop band, with people pulling us in different directions. There were pressures involved, and we didn’t know who to turn to. Now, there are more avenues for people with mental health issues. Thankfully, it’s better recognised.”

Nemes admits: “We weren’t very good at sticking up for ourselves. We should have told Arista to fuck off, that we were taking some time off. It was a confusing time. Our manager was great for having big, wacky ideas, but we would have benefitted from someone who was looking after us. Communication wasn’t very good, and we just didn’t know what was happening with Nick.”

As Marc summarises: “The management, record company and publisher were all older than us. They’d had experience of the tensions Nick was experiencing. Nick was clearly struggling, but the attitude was just: ‘Write the songs! Write the songs!’ We should have all been grown up enough, inside and outside of the band, to take the foot off the accelerator. Instead, greed, speed and vanity meant we drove into a brick wall.”

The demos for that second album, Junction Box, are on the new boxset. Opinions in the band differ on its merits: Les and Graham love them, Nick and Marc not so much. “They’re just works in progress,” shrugs Nick.

“I wasn’t happy with the sound and wanted it to be bigger. I’d been introduced to The Beatles’ engineer, Geoff Emerick, but I couldn’t convince anyone Geoff was the guy to produce us. I like the songs, but they’re just old demos, not a cause for regret.”

Marc points out that the three most finished songs, including the hit Whistle Down The Wind, eventually featured on Nick’s debut solo album, North Of A Miracle, noting: “The other songs have been sat on the shelf for a reason. I was excited at how they were sounding, but they weren’t finished.”

But Graham eulogises the punchy I Believe In Sundays in particular, while Nemes believes: “Junction Box would have been a much better album than Pelican West. We’d toured so extensively that we were really on our game, while Nick’s songwriting had gone to a whole new level.”

Just maybe, there could be a full-band second Haircut 100 album after all. With the 40th anniversary of Pelican West the obvious catalyst for a reunion, Nick has been writing songs that have proved suitable for – so far – Graham and Les to play on.

“They’re more towards the early Talking Heads punk side of Haircut,” muses Nemes. “They’re rawer and simpler than Pelican West, but with incredibly strong melodies.”

Whatever happens, there’s the Shepherd’s Bush Empire show in May to celebrate 40 years of our favourite comic strip heroes. All the band seem massively excited for the gig, hinting it might not be a one-off after all if it goes well.

The only issue for their comeback concert is how to play music with such rapid-fire intensity now they’re in their sixties.

Graham: “You could stick us on stage at a village hall tonight and we’d reel off Pelican West without too much effort. That’s the beauty of the bond we all have.” Marc: “Those songs are so fast. Listening to Kingsize, I think: ‘Oh fuck…’

“But I’m hopeful for the future. Once we’re all onstage bouncing off each other, we’ll inevitably want to do this again and again.”

Les: “Regardless how long it is since I’ve played, as soon as a Haircut 100 gig happens, it’s always ‘Off we go!’ and we’re playing full speed ahead.”

The final word goes to Nick Heyward, Haircut 100’s gentle, effusive singer, an underrated poet still in love with what bands can achieve: “Haircut 100 has its own energy. You can say: ‘We’re 61, of course we’re not going to play that fast now.’ But on the night, it might well be: ‘Woooah!’ We were a dynamo first time round. It’s no wonder I got knackered.

“Maybe we’ll need to calm down. But once Favourite Shirts starts up, before you know it, the band is flying and I’ll be thinking: ‘Oh God, it’s happening again!’”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!